The approach to novel reading in this unit

Teachers are encouraged to support as many students as possible to read and enjoy Playing Beatie Bow in its entirety. However, the reality is that some students may find this a challenge, while others may not feel sufficiently engaged. This is always a matter of judgement for teachers, especially in the middle years of schooling when there is one compulsory text shared amongst a diversity of students. In this unit, it is acknowledged that students may choose to not read the set novel and may resort to online plot summaries or the goodwill of fellow students.

In this spirit of openness, the unit makes no assumption or requirement for all students to read the entire book (or pretend to) though teachers may well encourage or even plead with students to do so! The value of this novel study lies in the opportunities presented by Playing Beatie Bow to open up learning and discussion in relation to three key points, which can be developed across this unit and within the assessment task:

- the evolution of the English language, including the impact of new technologies on language

- the genre of time travel

- broadening vocabularies in relation to the novel and the two points above.

Consequently, it should be enough for students to listen to the opening chapters read aloud in class (see Activity 3) and engage in the discussions arising and the activities inspired by the novel to successfully complete the unit.

At this early stage in the unit, teachers are advised to make this clear to students and alert them to the fact that there is one compulsory Receptive Assessment Task for all students. However, those students who do read the novel in its entirety will be at some advantage because they will have the opportunity to select one of two available Productive Assessment Tasks: either the Twitter Poem Task or the Time Travel DVD task. Those who choose not to read the novel should be advised to avoid the Twitter Poem task because of its reliance on a knowledge of narrative development across all thirteen chapters.

Outline of key elements of the text

Plot

Abigail Kirk finds herself transported back to the late nineteenth century and becomes embroiled in the family life of the Bows. The Bows will not let her return home believing that she is ‘the stranger’ who will preserve the family gift. (See the Goodreads website.)

Characters in Playing Beatie Bow

From the twentieth century: Abigail Kirk (formerly Lynette); Katherine Kirk (Abigail’s mother); Weyland Kirk (Abigail’s father); Justine, Vincent and Natalie Crown (neighbours).

From 1873: Abigail Kirk (time traveller), Beatrice May Bow (Beatie Bow), Gilbert Samuel Bow, Judah Bow, Samuel Bow, Robert Bow, Dorcas Tallisker (Dovey), Alice Tallisker (Granny).

- themes

- colonial and contemporary Sydney

- family love and values

- coming of age

- resilience and overcoming adversity

- identity

- hardship and poverty.

This unit will also explore the concepts of time travel and the evolution of the English Language.

Pre-reading activity

In order to accommodate all students, there will be a focus on close language study and the evolution of English to reflect a changing world, and particularly in relation to new technologies. Teachers should ensure that students complete the pre-reading activities before engaging with Playing Beatie Bow.

Activity 1: Puzzles of changing English

While Activity 1 may appear to be very complex, it is designed as a group puzzle with teacher hints along the way to support student success. Please see the teacher cheat sheet below:

| The original texts | Translation (to support teachers and provide hints for students as needed) |

| Text 1: From Chaucer’s Wife of Bath’s Prologue Middle English poetry from the 14th century (Lines 3–8) To speke of wo that is in mariage; For, lordynges, sith I twelve yeer was of age, Thonked be God that is eterne on lyve, Housbondes at chirche dore I have had fyve, — If I so ofte myghte have ywedded bee, — And alle were worthy men in hir degree. (and further in the Prologue, Lines 587–592) Whan that my fourthe housbonde was on beere, (from Poets.org website) |

Text 1: From Chaucer’s Wife of Bath’s Prologue Middle English poetry from the 14th century (Lines 3–8) I am going speak about the trouble with marriage; So, friends, since I was twelve, Thanks be to God (who is alive), I have married five men in a church; and if I’ve married so many men, Then all were worthy men to some degree. (and further in the Prologue, Lines 587–592) When my fourth husband was being cremated, You may wish to refer to this online Chaucer dictionary. |

| Text 2: Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Act 3, scene 1, 114–121 Shakespearean/Elizabethan English 16th – 17th century Ophelia: Indeed, my lord, you made me believe so. Hamlet: You should not have believ’d me, for virtue cannot so inoculate our old stock but we shall relish of it. I lov’d you not. Ophelia: I was the more deceiv’d. Hamlet: Get thee to a nunn’ry, why woulds’t thou be a breeder of sinners? |

Text 2: Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Act 3, scene 1, 114–121 Shakespearean/Elizabethan English 16th – 17th century Ophelia: Yes, Hamlet, you did. Hamlet: Well, you shouldn’t have believed me because all of us are rotten at the core, no matter how hard we try to be good. I didn’t love you. Ophelia: Well, I was tricked. Hamlet: Get to a convent, become a nun so that you cannot breed sinners like me. You may wish to refer to this online Shakespearean dictionary. |

| Text 3: From Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice An English novel from the early 19th century |

Text 3: From Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice An English novel from the early 19th century Everyone knows that a single, rich man wants to marry. Even if little else is known about him it is assumed that he is available as a potential husband for their daughter. |

Ruth Park’s Playing Beatie Bow

Late 19th and 20th century English/Scottish dialect

‘I dunna ken where your ain place is’, protested Beatie. I didna mean to go there myself. It were the bairnies calling my name. I dunna ken how I did it, honest. I never did it afore I had the fever’ As though to herself in a puzzled worried voice she said, ‘One minute I was in the lane, and the next there was a wall there, and the bairnies skittering about, and all those places like towers and castles and that…that great road that goes over the water, and strange carriages on it with never a horse amongst them, and I was afeared out of my wits, thinking the fever had turned my brain.’(Chapter 3, p. 46 in Penguin Classics edition)

Text 4:

Ruth Park’s Playing Beatie Bow

Late 19th and 20th century English/Scottish dialect

‘I don’t know where your place is. I didn’t mean to go there myself. It was the children calling my name. I honestly don’t know how I did it. I never did it before I got sick.’ As though to herself in a worried voice she said, ‘One minute I was in the lane and the next there was a great wall there and the children were playing around. There were towers and castles and a bridge that went over the water with cars going across it. I was afraid and thought I’d gone crazy.’If students need help with Scottish dialect, you might want to refer them to the online Collins dictionary.

Then download the Evolution of Language worksheet (PDF, 167KB) for this activity and print out copies for your students.

The activity requires students to examine the language used in a range of original texts from the fourteenth century (Chaucer) through to the twenty-first century (emoticons). Changes in the English language over time should become evident as the texts are explored. In the initial stages of the activity, groups of students should be given the original texts without the translations.

In small groups students work through the following steps:

- Try to decipher the language of each of the five texts included in Activity 1: Puzzles of changing English.

- Highlight in colour 1 all the words that are still familiar and spelt according to current spelling.

- Highlight in colour 2 all words that are similar but spelt differently.

- Highlight in colour 3 any words that mean nothing to you.

- Go back over the puzzle and see how much of it you can translate.

- You may wish to use the suggested online dictionaries to explore the meaning and origin of unknown words and to assist with the translation. For example, the root word of bairns in the passage from Playing Beatie Bow means child and has its origins in Scottish and Northern English language, barn child.

Students share with the class what they discovered about the evolution of the English language

- What evidence is there that English has changed over the centuries?

- Which words from the earlier texts are no longer used and which have evolved with new spelling?

- What is significant of these changes?

(ACELA1528) (ACELA1529) (ACELY1723) (EN4-2A) (EN4-8D) (EN4-2A)

Activity 2: An introduction to time travel and Playing Beatie Bow

The concept of time travel is central to the text Playing Beatie Bow. In the following activities students’ previous experiences and knowledge of the time travel genre are initially explored. Students will then watch a series of film clips and film trailers that explore the notion of time travel from 1936 to now. The intention here is for students to experience the different styles of film-making where the central dramatic device used is time travel. Students might also notice how film-making has changed with advances in technology, and with changing styles of acting and direction. After viewing each clip students might like to discuss their observations and initial reactions to the films. This discussion will support their success in the first rich assessment task.

Step 1:

In small groups, students make a list of time travel texts. These may include novels, films, TV series, comics and/or digital games.

Step 2:

Share with the whole class and create one large class list, which can be further developed and categorised (such as film, novel, TV series) during the unit. Teachers may like to consult lists such as Best Time Travel Movies and Goodreads for inspiration.

Step 3:

As a whole class, discuss which texts they have enjoyed/not enjoyed and why and how authors/filmmakers have used time travel as a device in these stories.

Step 4:

View a selection of the following time travel clips:

- Clip 1, The Time Machine (PG) was made in 1936 and is considered one of the earliest and best example of time travel in movies (2 minutes, 30 seconds).

- Clip 2, Back to the Future (PG) was made in 1986 and formed part of the Back to the Future trilogy (1 minute, 20 seconds).

- Clip 3, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (PG) is the third in the Harry Potter series made in 2004 (2 minutes, 50 seconds).

- Clip 4, Meet the Robinsons (PG) was made in 2007 and is an example of an animated time travel film (2 minutes, 30 seconds).

- Clip 5, Time (PG). Made in 2013 this short film was a Tropfest Finalist.

- Clip 6, Playing Beatie Bow (PG). The film was made in 1987 (6 minutes, 23 seconds).

Step 5:

Focus on Clip 5, and the question ‘if time travel were possible, what message would you leave in the future for someone in the past to find?’ Discuss with the class, or provide writing time for students to make a personal response by deciding what message they would want to leave for someone to find.

Step 6:

Watch Clip 6, Playing Beatie Bow. In this clip, students are introduced to the main characters, Abigail and Beatie Bow. They will see the pivotal moment where Abigail is transported from the twentieth century back in time to the nineteenth century. Watching this clip will visually provide students with contextual information about the setting: The Rocks in 1970s Sydney and 1873 Sydney Town. As well as this, the students will become familiar with the Scottish dialects and accents featured in the film. This is particularly important for those students who might find reading dialects and accents more challenging.

Step 7:

Using Google Maps show students the area in Sydney, New South Wales, where the story, Playing Beatie Bow is set and the clip is filmed: in and around The Rocks area.

(ACELA1528) (ACELT1622) (ACELT1621) (ACELT1623) (EN4-2A) (EN4-1A)

The writer’s craft and context

Playing Beatie Bow is a third-person narrative, structured around the time travel of an adolescent girl from 1970s Sydney to 1873 Sydney Town and back again without any apparent passage of time in her ‘real’ world. At the time of its release in 1980, the novel’s protagonist was a contemporary teenager living in the world of that time – its social mores, technologies and the urban and historical (re)development of The Rocks area of Sydney.

The novel moves between the more gentrified aspects of The Rocks in Sydney in the 1970s, to the early days of colonisation and the poverty and hardship of early settlers around Sydney Harbour. This time travel mystery follows the usual conventions of the genre. These conventions are one focus of study in this unit where students will examine the circumstances and particular requirements of time travel within Playing Beatie Bowand a range of other novels, picture books, films and television series. Students will consider the process of travelling backward or forward in time (a tardis, stepping through a wall, making a wish or wearing a dress with an antique crocheted collar) as well as the motivation, outcomes and insights of characters. For more background and a theoretical understanding of the time travel genre, please refer to the additional digital resources provided.

Given that Playing Beatie Bow was published in 1980, young people today will regard Abigail’s 1970s setting, devoid of internet and smart phones, as more historical than contemporary. For this reason, some points relating to the context of the 1873 Sydney Town and Ruth Park’s Sydney of the 1970s are worthy of brief mention here. Teachers and students may wish to research and learn more about either or both of these historical periods. Further resources of the historical detail and information about Australia in the 1870s and Australia in the 1970s can be investigated.

Ruth Park incorporates Scottish dialect and accents as a device to bring the early characters more alive as new settlers to the colony of New South Wales, and to further confound Abigail as she attempts to come to terms with the strangeness of the people and places she encounters in her time travel. While serving that literary purpose, it should be acknowledged that this use of accents, dialects and archaic vocabulary may create some challenge for young readers. For this reason, and to support an appreciation of the evolution of the English language, a pre-reading activity in this unit focuses on language use in the novel. See Activity 1 for more detail.

It is not only the syntax and language that have changed since 1873 and even the 1970s: it is also interesting to note that across the novel there is only one reference to the Aboriginal people of the time, despite the fact that Australia had been continuously occupied by the Eora people for thousands of years prior to European colonisation. On the revelation that the British Empire – that had been so powerful in 1873 – had broken down and no longer controlled the colonies that eventually formed Australia from the beginning of the twentieth century, Beatie asks Abigail:

‘But who’s looking after the black men?’

‘They’re looking after themselves,’ said Abigail. But Beatie could not understand.

‘Black men canna look after themselves. Don’t be daft!’

(p. 82, Penguin Classic Series, 2010)

This single reference is to Aboriginal men in general, rather than a character or a more gender-inclusive reference to people, signifying not only linguistic, but also social and political change.

Australian writers of twenty-first century fiction for young people would be more alert to the politics and significance of recognising traditional land ownership and abuses of the Aboriginal population during European colonisation. It may be instructive to provide students with a snapshot of the advance and persistent challenges of Aboriginal rights and the significant legal and political events since Ruth Park wrote this novel. In this way, students can see that literature can be a product of its time, and that Ruth Park may choose to include and acknowledge more of the Aboriginal experience if she were alive and writing today. Teachers will note that the extract is repeated as part of the analytical work to be undertaken by students in rich assessment task 1.

The novel is likely to resonate most strongly for students fortunate enough to visit The Rocks as part of the study of this novel, or with clear memories of having been a tourist at The Rocks and exploring the laneways, stairs and historical sites so well preserved today.

Activity 3: Read aloud

Understanding and rehearsing reading of this text is vital for teachers and strong readers who may like to participate in the classroom reading. The text includes dialects and accents and these are vital to understanding the culture and context of Abigail’s time travel. It may also be necessary to break the reading down into smaller manageable chunks because of some of the unfamiliarity of the language. This activity is designed to help students engage with and understand the language of the text.

Over intervals of time best suited to the students in your class, read the first three chapters aloud. This is to ensure that every student, regardless of their reading ability and disposition, has access to the text.

(ACELA1529) (ACELT1619) (EN4-8D)

Activity 4: Time travel in Playing Beatie Bow and other texts

In previous activities, students have explored time travel in a range of texts, and have listened to expert reading of the first three chapters of Playing Beatie Bow. After listening to and discussing the first three chapters, students will be in a position to commence filling in the time travel matrix (PDF, 133KB). It is suggested that students watch again the short video clips so they can examine the intertextuality across the genre, and consider how effectively Ruth Park employs the conventions of the time travel mystery within Playing Beatie Bow.

(ACELT1619) (ACELT1622) (ACELT1623) (EN4-8D) (EN4-1A)

Activity 5: Word investigations

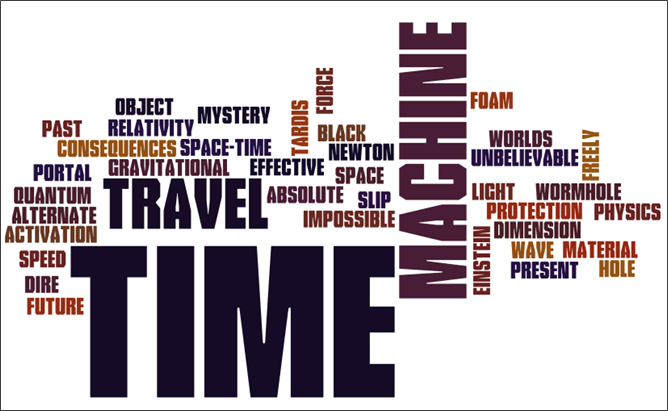

The focus of this next series of activities is the development of students’ vocabulary and specialist language. They will be introduced to the language frequently used within the time travel genre. The word clouds generated by the students will be used as part of the assessment for this unit. The final assessment task must contain evidence that the new and expanded time travel-related vocabulary has been used. The initial part of this activity will be teacher directed, followed by student group investigations.

Step 1:

Introduce the students to Wordle, a simple tool for creating effective word clouds. Ensure all students can see the word cloud as it is being created (interactive white board or data projector).

Step 2:

Type into the text box several words related to time travel. For example, alternate, portal, consequences, universe, activation.

Step 3:

Discuss the meaning, use and spelling of each of the words as they are listed. For example: portal. This word traditionally means gateway to other worlds but with the changes in technology it has evolved to mean a website that functions as an entry point to the internet and other related sites and services. Portal has its origins in the latin word porta, meaning entrance.

Step 4:

Ask students to contribute other words in order to built a more comprehensive and relevant list. A reasonable collective goal would be about 40 words. Once the list is generated select ‘create’. You can play with the result, changing colours, font styles and layout to create the desired effect.

Step 5:

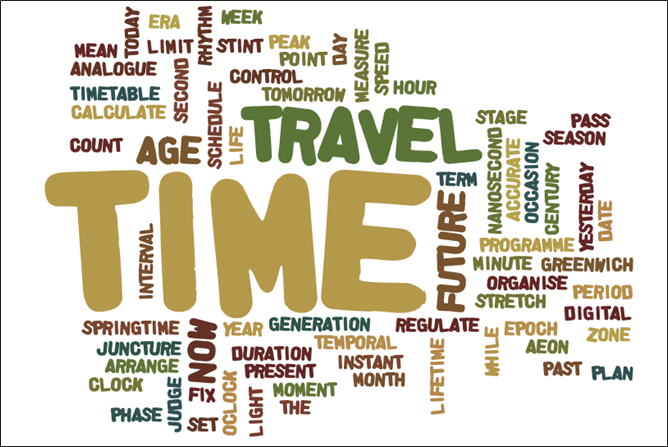

In small groups students select a word from the time travel word cloud. For example: time.

Using a print based or digital dictionary or thesaurus and the word search table example, students research the word looking for:

- the origin, or etymology

- the meaning

- other related words

- synonyms for the word.

Step 6:

Finally, students create their own wordle using the synonyms or the related words from their word search table.

Wordle activity example:

Home page

Text screen

Example word cloud: Time travel words

Example word cloud: Synonyms for the word ‘time’

Example: word search table

| Word | Meaning | Origin | Other related words | Synonyms |

| Portal | Gateway | Latin word: porta | Port, airport, passport, import, export | Passage, corridor, opening |

(ACELA1537) (ACELA1539) (EN4-3B)

Activity 6: Delivery ward

Consider the following story reported internationally in online and print journalism in November 2013.

Two baby boys born in Japan in 1953 had been accidentally swapped at birth by a hospital nurse. One boy grew up in the wrong home and endured years of poverty, hardship with limited education or opportunities. One boy, growing up in the other home, enjoyed a comfortable life with great opportunities for education, leisure and pursuing many different interests and friendships in life.

Over five decades later, a DNA test undertaken by the wealthy family, uncovered the mistake and the true families of both men were identified. The mix-up of the boys as newborn babies became the matter of a legal case and the boy who lived with the poor family was awarded approximately $400,000 compensation. He never got to meet his real parents, though because they died years earlier.

The news reported these comments from the man who discovered he had lived a life of poverty: ‘I wondered how on earth this could have happened,’ the man said. ‘I could not believe it. To be honest, I did not want to accept it . . . I might have had a different life,’ the man said. ‘I want [the hospital] to roll back the clock to the day that I was born.’

This story was accessed via The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 November 2013.

Students revisit the time travel matrix (PDF, 133KB) they used to identify the components of the time travel genre. Using their imagination, take this news story and craft the basic ideas for a time travel mystery. What conventions could you provide to get this poor man back in time to avoid the fateful baby swap that took place sixty years earlier? You will see that the bottom line of the matrix is free for this purpose.

Image of Japanese baby and mother

This image has been licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported licence.

Ways of reading the text

In this unit, students have focused on the three key points outlined earlier:

- the evolution of the English language, including the impact of new technologies on language (Activity 1)

- the genre of time travel (Activities 2, 4 and 6)

- broadening vocabularies in relation to the novel and the two points above (Activity 5).

Accordingly, the rich assessment task (below) and the choice between productive assessment tasks A or B (see the following tab) provide students with two opportunities to demonstrate their learning and knowledge and meet the demands of the curriculum. These are conceptualised as assessment for and of learning so it is recommended they are worked through in class with support rather than set as homework tasks.

The author and novel’s significance in the wider world are integrated across the activities and the assessment tasks. At various points, students are required to address each of the elements:

- reading the text from a range of perspectives

- an examination and understanding of genre and intertextuality

- significance within Australian literature and ways of viewing the world

- evaluation of the text and analysis of language and themes.

Rich assessment task 1 (receptive)

Textual analysis of Playing Beatie Bow

This task invites students to undertake a close, critical reading of an extract from the novel as well as make intertextual connections with the film trailer and a review. This is a high order task, and in line with the Australian Curriculum Performance Standards for Year 7:

By the end of Year 7, students understand how text structures can influence the complexity of a text and are dependent on audience, purpose and context. They demonstrate understanding of how the choice of language features, images and vocabulary affects meaning.

Students explain issues and ideas from a variety of sources, analysing supporting evidence and implied meaning. They select specific details from texts to develop their own response, recognising that texts reflect different viewpoints.

Please see the student materials below for full details of the task. It may be necessary to provide some background, including maps, to demonstrate the power and decline of the British Empire.

The texts provided for analysis are:

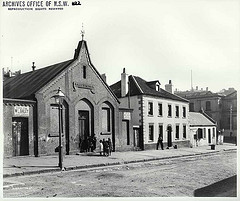

Text 1: Extract from the novel

Text 2: A photograph of the Ragged School

Text 3: An extract from the film version

Text 1: Extract from the novel

Yet Beatie was relentless in her questioning of Abigail about the years to come. Abigail told her about jet aircraft, about men landing on the moon and their voices and pictures coming to all the way to earth, clear and bright. She told her about new countries that did not exist in Beatie’s day.

‘But where is the Empire?’ Beatie asked, baffled.

Abigail did not know. ‘It just seemed to break up and dribble away,’ she admitted lamely.

‘But who’s looking after the black men?’

‘They’re looking after themselves,’ said Abigail. But Beatie could not understand.

‘Black men canna look after themselves. Don’t be daft!’

Most of all she wanted to know about people, whether girls could become doctors, teachers, do good and useful things. Abigail was glad to be able to say ‘yes’.

Always these conversations ended the same way.

‘But how did those bairnies know my name? Dinna ye ha’ some more ideas, Abby? I tell ye, I’m ‘ettling to find out, come what may!’

The older children at the Ragged School had their lessons after dinner-time whistle, a midday orchestra of hideous noises from steam cranes, factories and loading ships. It was taken for granted by the Ragged School board that the children worked for a living. Some were boot blacks or newspaper boys in the city; other ran errands for offices, or delivered for merchants; many youngsters did something, anything, to earn a few pennies, and many of their parents resented their wasting afternoons at the Ragged School.

(extract from Playing Beatie Bow, pp. 82–83, Penguin Classic Series, 2010)

Text 2: A photograph of the Ragged School

This image has been licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported licence.

Text 3: An extract from the film version of Playing Beatie Bow

Watch the trailer.

Questions

Please note that you are required to:

- provide evidence from the texts to demonstrate how you reached your conclusion – this aspect of each question is highlighted in bold

- use full sentences

- edit carefully

- use and highlight words from the word clouds developed in this unit.

- How does the world Ruth Park creates in Text 1 and the Text 2 photograph convince you that both are historical places and people? Choose at least one sentence from Text 1 and one detail from Text 2 to demonstrate how you know that they are both historical worlds.

- Using the film extract, describe how the filmmakers attempted to capture the world of the 1980s as well as the world of 1873. Commenting on the film extract you watched as part of this task, explain whether you thought that this was convincing or not.

- Describe how an alternative film or novel you have seen or read revealed a transition from one time to another. You will need to describe briefly the technique(s) used to make the transition effective for the audience.

(Between 75 and 120 words for each question.)

Please ensure that students understand and have access to the rubric (PDF, 107KB) designed for this task.

(ACELY1726) (ACELA1782) (ACELT1619) (ACELT1620) (ACELT1621) (ACELT1803) (ACELT1622) (EN4-2A) (EN4-1A) (EN4-8D) (EN4-5C)

Rich assessment task 2 (productive)

In this unit, students may choose between either task A or B.

Those who have not read the novel in its entirety should be advised to select task A where they will draw upon their learning in relation to time travel and language. That task does not assume a close knowledge of each chapter of Playing Beatie Bow. Task B, on the other hand does presuppose knowledge of the full narrative structure and ideas of the novel.

While managing two assessment tasks may introduce a level of complexity, it does have the advantage of allowing some differentiation of assessment to a support success for all students. Further to this, it may open up opportunities for sharing of student learning and products. All students might benefit from hearing and reading the collective ‘pitches’ for time travel mysteries and the Twitter poems that capture the essence of Playing Beatie Bow, and teachers may wish to build in some speaking/listening content and performance standards.

(ACELY1719) (ACELY1804) (ACELY1720) (EN4-1A) (EN4-3B) (EN4-4B)

Productive assessment task A: Pitching a time travel mystery

The task:

In this assessment task, students will be given the opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge of the conventions of the time travel genre in an imaginative and creative way. They are asked to imagine they have been given the opportunity to pitch a time travel outline to a major Australian film producer. Building on knowledge developed in previous activities, students will use the time travel matrix (PDF, 133KB) (activities 4 and 6) to create the outline of their time travel narrative.The focus here is not on writing a full narrative. Instead, students will be required to show their mastery of the time travel conventions by constructing a simple storyboard and translating it into an imaginative, marketable DVD cover. (Students may wish to access the DVD Cover Maker app available for 0.99c in the iTunes store.)

All narratives are to be set in present day Australia, with the main characters travelling backwards in Australian history, or forwards into an imagined Australian future. As outlined in the beginning of this unit, one of the main points of focus was the extension of students’ vocabulary and knowledge of specialised language. For this reason, students are required to highlight, on the DVD cover and in the matrix, incidences where they have used any words drawn from the word clouds in Activity 5.

Before commencing the activity it is vital that students:

- have explored the demands outlined in the rubric (PDF, 120KB)

- EITHER research the historical period they will return to OR design and understand the future world that will be the basis of their story.

The storyboard for the time travel narrative

Student storyboards should provide answers to the following questions:

- What is the time travel device?

- How does the time travel occur?

- Why are the characters travelling in time?

- What causes the time travellers to become stuck in time?

- What are the possible consequences of this time travel?

The DVD cover and suggestions for presentation

Students will use the elements and features of a standard DVD cover to create their own. For example, title, images, blurbs, reviews and ratings. A range of DVD covers could be examined to provide inspiration and alert students to the elements used to entice and engage their prospective audience. To create their DVD cover students may choose to use PowerPoint. It allows for easy access and editing as well as eliminating the need for colour printing. It is not, however, anticipated that the PowerPoint will be used for public presentation. If a print copy is required, students should save their PowerPoint as a PDF prior to printing.

(ACELA1537) (ACELA1539) (ACELT1619) (ACELT1621) (ACELT1623) (ACELT1805) (ACELY1725) (ACELY1728) (EN4-3B) (EN4-8D) (EN4-1A) (EN4-4B) (EN4-2A)

Productive assessment task B: From prose to Twitter poetry

Students will be synthesising and re-creating Playing Beatie Bow as a collection of Twitter poems.

One of the key focus points of this unit has been the evolution of the English language and the impact of social and technological change. The following activity is designed to engage students in a practical and aesthetic exercise where they learn about and practice the conventions of Twitter, which was one of the fastest growing social media and news platforms in 2013.

Twitter has about 127 million active users and is in the top ten most visited websites. According to a 2012 infographic, more women than men use Twitter and 58% of users are 35 years old or more. Many teachers are beginning to engage with and use Twitter while others are wondering how on earth to get started or how to decipher Twitter jargon such as retweet, hashtag and handle. This is a perfect example of English as a living language subject to the speed of change. Simply watching television is evidence enough of the staying power of Twitter given the number of programs that invite and display twitter ‘feeds’ across their screens, and this is as much the case for current affairs as it is for reality television. This highlights how technology is being used to create engagement and interaction between audiences and the people on our screens. Twitter has been particularly influential in the delivery of news services, journalism and even emergency services. On ABC TV news, it is now the practice to include a journalist’s twitter handle (name) on the screen during all telecasts.

Twitter is a signficant source of information and news that merits some attention in the classroom. While some of this will be very familiar to many teachers, it is also an ideal opportunity for others to learn about Twitter either in private or as a classroom demonstration of how adults have to constantly learn to keep up with changes in language and technology. Consider the following range of resources and select those most relevant to you at this time. If you are new to Twitter, perhaps recruit a colleague to start up with you so that you have a practise partner:

- a general introduction video (and did you know that you can click to get the transcript for this and most YouTube videos?)

- Twitter guide to getting started or perhaps help you progress your engagement and account

- a guide designed for educators signing up to and using Twitter.

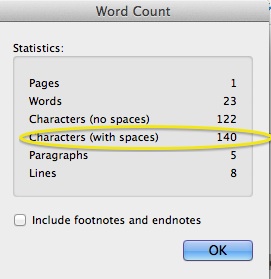

For the purposes of this activity the most significant fact about Twitter is that any message has a limit of 140 characters including spaces, so if you know nothing else, this may be enough!

There is a growing community of Twitter poets and numerous Twitter accounts to follow. An article about Twiterature is a great source of ideas and links to accounts, and an article from The Independent offers a more scholarly angle.

Inspired by this knowledge and the creative uses to which Twitter is put, students here have an opportunity to try out their Twitteresque flair as an expression of their knowledge of Playing Beatie Bow. Rather like the old plot summary, but with a more aesthetic and demanding twist, students are required to reduce each chapter of the novel to just one twitter poem. Students might be put in groups to undertake this task, though some may wish to do it solo. Teacher knowledge of student reading skills will determine how this task is best undertaken by particular students and cohorts.

In order to support teachers and the students, the writers of this unit have produced Twitter micropoems to represent the first three chapters of Playing Beatie Bow. This model may also help teachers decide how best to organise individuals or groups:

| Chapter 1 | Steel and glass tower in The Rocks.Abigail making a dress: Edwardian curtain and yellowed crochet, tiny initials, A.T.Playing Beatie Bow |

| Chapter 2 | Parents and dismay How powerful is love?Baffled she scrambled after the little furry girl.Horse manure, tidal flats, sewerage. Where was she? |

| Chapter 3 | No Bridge No Opera HouseFoul debris a black toothless mouthPain so sharp Goodness in gentle handsThe gift and the stranger. |

The creation of the poems was a three step process as illustrated in the Twitter Poetry Handout and as explained here in a three step process:

Step 1:

Go through the chapter and type up those sentences or phrases that seem to be most significant to understanding the setting, the characters, themes or symbols. These extracts must be word for word and placed in column 1. It is only possible to do this really well after having read the novel. In the example provided, you will see that the writers got clever by Chapter 3 and were much more selective about what they chose to type up in column 1 to reduce the word load.

Step 2:

Copy and paste column 1 into column 2 and begin to delete words, leaving a much smaller shell. Notice that sentence structure is disregarded as the writers focus on the words or images that carry most meaning.

Step 3:

Copy and paste column 2 into column 3 and keep reducing the poem until there is a maximum of 140 characters including spaces. You will notice that the writers chose to use stanzas and reorder some words and lines to enhance meaning and sound.

The word count function is important here and can be found in the drop down menu for the Tools function in Microsoft Word. Students should be guided to use the word count function as a means of ensuring that they abide by the strict criteria of Twitter: a maximum of 140 characters including spaces.

Now it’s the students’ turn, either in groups or individually, according to need and context. To complete this task successfully, however, students do need a good knowledge of the novel in order to discriminate between what is vital and what is less so.

The process is to complete the reduction of each chapter to create a Twitter poem (maximum 140 characters including spaces).

Students should then compile the 13 Twitter poems, that is, one for each chapter, to represent the novel in its entirety.

Final presentation:

The presentation of the poems, whether in print or on screen, with image or not, whether read aloud or not, is open to teacher judgement. As always, the rubric should serve as the point of reference for students and teachers to ensure that they are meeting criteria and performance standards. Please note that the criteria may need to be amended if there is a performance element that teachers may wish to address.

(ACELT1619) (ACELT1623) (ACELT1625) (ACELT1805) (ACELY1723) (ACELY1725) (ACELY1726) (EN4-8D) (EN4-1A) (EN4-6C) (EN4-4B) (EN4-2A)

(8 votes, average: 3.50 out of 5)

(8 votes, average: 3.50 out of 5)