Introductory activities

Before reading

Context

It will be useful to have students consider the links between their study of Anderson’s text and their knowledge of Australian history, especially the circumstances of the Great Depression, Australia’s participation in the Second World War and even post-war migration. It would also be useful to begin the unit with a brief study of the Tennyson poem ‘The Lady of Shallot’ to familiarise them with the metaphorical basis for Anderson’s novel.

Students can construct a timeline using information from the internet on Jessica Anderson.

Assumptions

The following questions might be introduced in the early phases of teaching to test what students expect about Anderson’s novel.

- What do you expect will be the subject matter and themes of a novel about an elderly woman returning to her childhood home?

- Could such a novel possibly bear any relevance to your own life? If so, what might be that relevance?

- Can setting represent the inner self? How might a change of setting from Queensland to the culture, architecture and climate of London affect the inner landscape?

Activities

- Pre-reading: Students can go to Google images to find book covers of Tirra Lirra by the River. They can organise these chronologically as a Pinterest presentation. They should creatively annotate with comments on what each cover suggests the book will be about. It is a good idea to return to this once the book is read to judge their expectations.

- Commenting on the book: While reading, students can look at the comments made about Jessica Anderson’s text on the ABC Book Club site and they can add their own comments.

While Reading

Plot

Anderson’s narrative is not a linear plot; her series of back-stories and interludes is best characterised as a non-sequential narrative. Anderson’s text is arguably a classic ‘stream of consciousness’ narration drawing heavily on discursive thoughts and memories. There are stylistic decisions in this form of plot which mirror Nora’s febrile and dazed frame of mind as she dozes in and out of her consultations with the troubled Dr Rainbow. The text is also without chapters.

The narrative arc begins with Nora’s somewhat forced return to her Queensland childhood home (latterly Grace’s home); she quickly develops pneumonia, a strange and unsettling illness that plays havoc with her memory and general state of mind. Her confinement makes her dependent upon a neighbour (Betty Cust), with whom she soon grows familiar, and another neighbour (Lyn Wilmot) whom she resents, not least for the reason that the reluctant nurse is a mercenary in the paid employment of the Custs and whose domineering and brutal manner strongly reminds her of Una Porteous, her former mother-in-law. The narrative draws back and forth between the present and the past, notably chronicling Nora’s lonely childhood in the aftermath of her father’s sudden death and her unhappy marriage to Colin Porteous who eventually leaves her for his young lover, Pearl.

A strong focus is placed upon Nora’s time spent in the company of a bohemian set in Potts Point, including Ida Mayo and Lewie Johns, the former a dressmaker and the latter a homosexual artist with whom Nora strongly identifies, despite the protestations of her straight-laced husband. The narrative then continues in a reasonably linear manner chronicling the elderly Nora’s back-story, occasionally cutting back sharply to the bed-ridden Nora to highlight the humour and irony of present events, and to focus on her emerging curiosity about the history of her treating physician, Dr Gordon Rainbow, the son of an old childhood friend, the late Dorothy Irey.

The ‘events’ of the text are all resurfaced memories of the central character and narrator, Nora, but upon closer examination Anderson presents this resurfaced memory as the inevitable result of a lifetime of wilful repression; Nora’s memory ‘globe’ is spinning out of control and, with her life drawing to a close, there is little time to hide away the dark and painful events of her life: a lonely childhood and subtle rejection of her mother, a London abortion, a suicide attempt, the abandonment and final struggle of her cat Belle, and the face of her late father (whose colourful and horse-drawn funeral ceremony surfaces on the very last page of the text).

Plot activity

The plot is a non-sequential narrative, a series of flashbacks, drawing in and out of Nora’s memories on her return to her childhood home.

Ask students to represent the plot diagrammatically. Some should:

- map the events of her life in a linear manner or

- represent the way the events of Nora’s life unfold through her memory. For example, connections might be made between her father’s funeral – depicted on the last page of the text – and a colourful illustration of that ceremony’s plumed horses in the funeral cortege against another bubble representing Nora’s work as a theatrical costume designer in London.

They then compare what is gained and what is lost by each approach to the representation.

(The purpose of a non-sequential mode would be to visually represent the underlying purpose of Anderson’s flashbacks – highlighting the way that memory itself collides and ‘bumps into’ itself and overlaps to form an overall impression of one’s reality).

They use these representations to discuss how the novel raises the questions:

- What is our actual reality? Is it the events in our lives or is it the memory of those same events?

- To what extent do our (repressed) memories of events determine our choices in the present?

Character

The novel is set around the lifetime memories and experiences of Nora Porteous, nee Roche, whose character is typified as one of introspection and artistic response, yet one whose willingness to act whimsically and on impulse is off-set against a natural caution and fear of conflict. Introduced to us as “the shape of an old woman who began to call herself old before she really was”, her exhaustion from her travels leads us to think of her as frail but as the novel progresses we learn of her creativity and strength.

Each of the other thirty-eight characters who occupy Nora’s memory are all bit-players in the over-arching scheme of things, given that Nora does not effectively bond with any one of them as a life-long friend; even her memories of the legendary ‘number six’ which she shared with Hilda, Liza and Fred in London are soured by her sudden removal from that place, Fred’s mental illness, and the increasingly detached tone of her letter correspondence with Hilda and Liza.

a) Character activities

Listen to reviewer Geordie Williamson’s opinion (702 ABC Radio Book Club) that Nora Porteous (unlike the author Jessica Anderson) never quite realises that she’s an artist. Do you agree? Is this a misinterpretation of the text? Is Nora rather simply shy and humble? Or is her unwillingness to embrace her artistic talent a feature of her antagonism towards her sister Grace, whom she felt subtly derided her artistic temperament as a child?

b) Exploring relationships

Particular focus might be placed on Nora’s relationship to the following characters: her sister Grace, Olive Partridge, Betty Cust, Ida Mayo, Lewie Johns, Arch Cust and her late father.

Allocate a character other than Nora to each small group of students to write and present a monologue, interior or to another person, in which Nora explains the importance of the character in her life.

To develop the material for the monologue, students will need to work through the following activities:

- Groundwork: Identify each of the passages in the text which refer to that character and detail the events and places relating to their relationship with Nora.

- Analysis: Explain Nora’s feelings toward the character (e.g. Nora associates her happiest childhood memories in the company of the novelist Olive Partridge, but also later experiences the pang of self-pity at her growing estrangement from her childhood friend after Olive marries and moves overseas).

- Synthesis: Decide how you are going to explain the role of the character in Nora’s life – their key importance.

- Developing Nora’s voice: Identify how Nora’s perspective of this character is represented through choice of language and reflect this use of language in your monologue.

c) Explore character pairings

Who does Anderson present as a doppelganger or ‘pairing’ to your chosen character?

| Lewie Johns | David Snow |

| Lyn Wilmot | Una Porteous |

| Peter Roche | Fred |

| Arch Cust | the nameless American lover |

| Doctor Smith | Doctor Rainbow |

| Colin Porteous | John Porteous |

| Hilda | Liza |

The pairing might also be extended to Nora’s Queensland childhood home and ‘number six’ in London.

- What is the significance of these pairings in the novel?

Female and Male characters

The female characters are complex, nuanced and sophisticated. They are often oppressed by men. It is difficult to identify a single male character who possesses genuine strength, intelligence and kindness, with the possible exception of nephew Peter Chiddy. We remember instead the whimsical and shallow Lewie Johns, the calculating and controlling Colin Porteous, the cryptic and dour Dr Rainbow, the callous newsagent, Mr Cust, the sexually-precocious Arch Cust whose father defends his frustrating and hurtful behaviour, the cowardly American adulterer aboard the ship who avoids Nora’s glance in the presence of his wife, the wholly unreliable (if mentally ill) Fred who causes Nora, Hilda and Liza’s eviction from their London flat, and the mercenary landlord, Mr Pope.

Discussion questions:

- Is Colin Porteous ultimately explored to a degree which offers insights into his shallow character?

- Do any of the male characters remain unscathed by the light brushstrokes afforded their personalities, integrity and intellects?

Have students consider the way that the fate of male characters is represented against that of female characters. What conclusions can we draw about the role of women at the time of the novel?

Personal connections with students’ own experience

Students might be guided to consider the personal connections they draw to Anderson’s text with the following questions:

- To what extent is Nora’s experience universal (or common to everyone)? Is there anything actually extraordinary about Nora’s life which makes her inaccessible to you as a character, or else a character whom you are never likely to meet?

- To what extent do you agree with the idea that Anderson deliberately created an ordinary Australian woman so that we might better relate to her experiences? Are her experiences ordinary or are they indeed extraordinary?

Identification with characters and situations

The students discuss the issue of how we identify with a character in a novel.

To what extent do we sympathise with Nora and understand why she behaves the way she does considering such issues as:

- the individuality or commonality of her life experiences

- her actions that would be criticised, particularly at the time in which they occurred historically

- the form of the novel as first person narration and detailed confessions, softening our censure.

Synthesising task/activity

On completion of the text students discuss these statements, giving evidence for their opinion:

- The power of Anderson’s text is that she has created a subtle, refined and sophisticated inner world of her central character.

- By extension, Anderson’s text causes us to reflect that most lives are as detailed, remarkable and challenging as that experienced by Nora.

- The purpose of creating such a character is to demonstrate that even the most seemingly ordinary of lives possesses a rich and powerful dimension of experience and understanding.

The students write an essay discussing the statement:

In Tirra Lirra by the River, Jessica Anderson has successfully trodden the line between presenting an ‘ordinary’ person with whom we can relate and an ‘extraordinary’ character worthy of fiction.

The Writer’s Craft

Structure

The text is centred around the intermittent and free-falling memories of Nora Porteous upon her return to Queensland, her ‘globe’ of memory spinning out of control and revealing the hitherto hidden events of her long life.

The novel is without chapters but arguably cast in three acts:

- ACT I: Nora’s return to her childhood home to Colin Porteous leaving her for Pearl

- ACT II: Nora’s divorce and her knowledge of Ida Mayo’s death

- ACTIII: The end of the mail strike and the final, belated memory of her father’s funeral.

This structure reflects the three acts of Nora’s life: her childhood and early marriage; her life as a single woman and dressmaker in London; and her old age in Queensland, which the novel leaves unresolved.

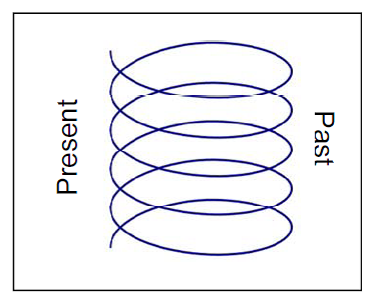

It moves in a helical form beginning in the present and fluidly picking up memories from the past, vignettes of Nora’s formative years, until we have a sense of her character as she moves into old age.

Acknowledgement: Wikipedia commons

This structure allows Anderson to create tension during Nora’s first day at her family home, as so much is not understood by the reader, and to reveal events and relationships from her past, one by one, as the spring uncoils.

Setting

The Queensland setting is used to strong effect to symbolise the rejuvenation of Nora’s mind. Conversely, the London setting later in the novel is drawn upon to capture Nora’s confinement and equal sense of comfort, which reminds her of life at Potts Point.

The early setting of the text in the Queensland countryside portrays Nora as a woman who discovers her sense of self in nature. The landscape setting strongly evokes the early Romantic context of the novel, and complements Nora’s communion with nature as a teenager as a way of understanding puberty and early sexuality. Setting is also a way of symbolising Nora’s emerging sexuality (p. 14).

The setting in this most interior of novels is centred on poetry as a means of providing inner landscape.

Consider page 12:

My other landscape absorbed me. And later, when I was mad about poetry, and I read The Idylls of the King and The Lady of Shallot, and so forth, I already had my Camelot. I no longer looked through the glass. I no longer needed to. In fact, to do so would have broken rather than sustained the spell, because that landscape had become a region of my mind, where infinite expression was possible, and where no obtrusion, such as the discomfort of knees imprinted by the cane of a chair, or a magpie alighting on the grass and shattering the miniature scale, could prevent the emergence of Sir Lancelot.

The topic sentence introduces the idea of “other landscape”, which is replaced “later” by poetry and becomes a “region of my mind”.

What is the power of that “region of my mind”?

In contrast Anderson also describes the “outer landscape”. Students should explain how setting is used in this passage and contrast it with the passage above:

Often, I used to walk by the river, the real river half a mile from the house. It was broad, brown and strong, and as I walked beside it I hardly saw it, and never used it as a location for my dreams. Sometimes it overran its banks, and when the flood water receded, mud would be left in all the broad hollows and narrow clefts of the river flats. As soon as this mud became firm, short soft thick tender grass would appear on its surface, making on the green paddocks streaks and ovals of richer green. One moonlit night, coming home across the paddocks from Olive Partridge’s house, I threw down my music case, dropped to the ground, and let myself roll into one of those clefts. I unbuttoned my blouse, unlaced my bodice, and rolled over and over in the sweet grass. I lay on my back and looked at the moon, then down my cheeks at the peak of my breasts. My breasts did not have (nor did they ever develop) obtrusive nipples, but the moon was so bright that I could clearly distinguish the two pink discs that surmounted them. I fell into a prolonged trance. (pp. 13 – 14)

‘Landscapes’ in the novel

Students consider ideas about the role of place and landscape in Anderson’s work, defining and providing examples of each landscape in the table below. They should consider how these landscapes add to the effect and meaning of the novel.

| Kind of landscape |

Examples | Significance to the novel |

| Physical | ||

| Social | ||

| Remembered | ||

| Imagined |

Narrative Voice

Students should consider each of these “voices” and locate other examples.

- Nora’s confessional voice: Consider the way in which Nora’s voice engages in a tone of self-confession throughout. An example of this might be found on page 11: “I have one rather contemptible characteristic. In fact, I have many. But never mind the others now. The one I am talking about is my tendency to be a bit of a toady. Whenever I am in an insecure position, this is what happens. I massage the smile from my face by pressing the flesh with my fingertips, over and over again, as I used to do when I had that facelift, all those years ago.”

- Detachment from self: Students should consider the way that Nora represents the detachment from herself as early as page 2: “Through the long mirror of the big black hall-stand I see a shape pass. It is the shape of an old woman who began to call herself old before she really was, partly to get in first and partly out of a fastidiousness about the word ‘elderly’, but who is now really old.”

- Detachment from others: Nora seems to be incapable of being shocked. Students consider her description of: her brother’s early death; the attempted seduction of girls who passed the four boys under the camphor laurels; the death of the same boys in the First World War; the axe murder of the Rainbow family by Dorothy Irey. To what extent are these the reactions of a woman remote from those around her or the effect of reflection on times past?

- Reliability: Is this confessional style of narrative an attempt by Anderson to portray Nora Roche as a reliable voice, or is it almost deliberately deceptive? The approach to characterisation is one which draws upon the irony of an increasingly shocking voice; Nora is not the supposedly conservative ‘old’ woman we are introduced to in the novel’s earliest pages.

Language and Style

Have students consider the effect of the following language and find other examples:

Present tense: “Lyn Wilmot’s resemblance to Una Porteous is becoming more remarkable by the minute.” (p. 71)

Simple sentences: “The Depression was over.” (p. 87), “My brother was killed in the trenches in France.” (p. 22), “My mother didn’t like me much.” (p. 20)

Complex sentences: “But even as I shook my head, my interior eye was assailed by a medley of rich rippling colour, of bright lights and inhabited shadow – all latterly derived from the theatre, no doubt, but first of all from Ida Mayo’s hands manipulating satins and brocades beneath her little lamps.” (p. 158)

Symbolism: The father of the introspective narrator (whose inner landscape is poetry), worked as a “surveyor in the Lands Department.” (p. 22)

Rhetorical questions: “Who was I? Nora Porteous, nee Roche, thirty-five, domestic worker, amateur dressmaker, detested concubine, and student of the French subjunctive tense.” (p. 86)

Metaphor: “My enemy had entered my hut and was squatting in a corner, waiting.” (p. 87)

Extended metaphor: Memory as embroidery, (p. 161) Oppression as a bird or “breast breaker” (p. 174), Memory as a globe (p. 201)

Irony: “The axe is an offence, evidently, against the aesthetics of murder.” (p. 182)

Motif: threads and sewing.

- To what extent is the final stylistic flourish in Anderson’s work a reference to the extended metaphor of embroidery and dressmaking in the novel? Is reality ultimately represented as an ever-changing embroidery in the lap of Nora’s memory?

- Is reality represented as an unreliable and transient series of threads whose grand design may not be known until the final stitches or, in narrative terms, the end of Nora’s life?

- To what extent do you think Anderson has successfully drawn upon the repeated imagery of Nora’s disregard for bad cutters of fabric – and the novel’s shocking revelation of Dorothy Irey as an axe murderer and therefore the ultimate “bad cutter”?

- Does the novel successfully portray its “bad cutting” references as a symbolic mark of Nora’s sub-conscious “bad cutting” of her own memory?

Using the examples above and any other elements of style they can find, students should write a paragraph on Anderson’s skill as a writer.

Themes and Ideas

Themes

| Quest for independence | Relationships between men and women | Search for connection |

| Loss of innocence | The importance of self knowledge | The nature of memory |

The text carries numerous and interwoven subjects and themes which crescendo at the novel’s end when Nora finally remembers something about her late father, albeit his face is still impassive, and it is only the memory of his funeral. Have students search for evidence of the above themes (or else their own chosen themes) and show how each theme is developed through the text.

- The nature of memory

Within this particular theme, Anderson carries her strongest and most enduring metaphors:- memory as a “globe” spinning and concealing the darker, painful events of life (p. 36)

- memory as a theatrical stage (p. 47)

- memory as an act of abortion (or “curette”) (p. 117)

- the limitation of photographs to evoke memory (p. 144)

- physical sickness as the manifestation of a repressed memory (p. 145)

- memory as embroidery (p. 161)

- memory as “truthful fiction” (p. 200)

How has Anderson drawn upon other symbolic aspects of the text to reference memory?

- The treatment of women in Australian culture

Draw students into a discussion about the treatment of Nora as a young married woman seeking work in the country during the Great Depression. How is this represented in the prose?- Why does Olive Partridge decide to leave Australia and does Anderson explore Olive’s expatriation as a feature or result of overt sexism?

- How is Ida Mayo depicted within the context of Bomera? Is her matriarch-like status a function of her position within the artistic world? Or is it because men in the artistic world are depicted as unimaginative and parasitic?

- Why does Anderson draw parallels between Una Porteous and Lyn Wilmot? What is the purpose within her narrative?

- Other themes

Have students research the following passages in the book and draw conclusions about the themes to which they relate:- Pages 36–37: Nora considers her memory a “globe” which sits upon her head.

- Pages 86–88: Colin Porteous brings home his lover Pearl to meet Nora and announce his intention for a divorce.

- Pages 112–114: Nora’s curette in London.

- Pages 125–127: Nora Porteous becomes a fully-fledged dressmaker in London.

- Pages 134–138: Nora’s quasi-sexual experience with Arch Cust.

- Pages 154–156: Nora’s attempted suicide.

- Pages 158–160: Nora begins work as a theatrical dressmaker in London.

- The ending

Have students examine the final two pages of the text and consider how the conclusion synthesises the major thematic strands of the text.

Activity: Revisiting expectations

Now that the book has been read and discussed, students can return to the book covers that were found on Google images (See the activity under Initial Response).

As a teacher, you might model a response about the book cover by beginning with the Picador (Pan Macmillan Australia) edition, 2011. Their discussion might include the following aspects:

- The positioning of a mannequin’s torso in the centre of the image: is this simply a reference to Nora’s occupation as a dressmaker? Or is it more emblematic of a symbolic layer of her personality – one where her life experiences have shaped and clothed her?

- The dark green colour rising up against the model’s torso: is this a colour reference to the idea of the river rising? Is it the river which symbolically bears her towards her Camelot? Or is it a more oblique reference to the water rising in her lungs which then carries her memories (pneumonia)? Or is the book cover suggesting the confluence of Camelot, the river and Nora’s febrile memories as a result of her illness?

- The scraps of the printed work on the torso and the written instructions surrounding the torso: is this scrap newspaper collage a reference to words and language as elements at the core of Nora’s being? Or is it a subtle reminder of a Dada work of art –approximating or foreshadowing Anderson’s experimental ‘stream of consciousness’ style which first surfaced in literature during the same era as Dada art?

(ACELR062) (ACELR063) (ACELR065) (ACELR066)

Meaning and Context

How does Anderson use the events of Australian 20th century history to develop the symbolic aspects of her novel, and the characterisation of Nora’s life?

Consider the use of the First World War, the Great Depression, the Second World War, the mail strike, communism and psycho-analysis.

In particular:

- “The winter of 1939-1940 was extremely severe. Every time I got on my feet, down I would go again, to lie in bed coughing.” (p. 126)

- “Whenever I think of communism I see something grey.” (p. 115)

- “The Depression was over . . . Three months after I had begun to earn money, Colin came home with a girl. ‘This is Pearl,’ he said.” (p. 87)

- “And I would probably have said, yes, of course, because in these times, when sexuality is so very fashionable, it is easy to believe that it underlies all our actions. But really, though I am quite aware of the sexual nature of the incident, I don’t believe I was looking for a lover. Or not only for a lover. I believe I was also trying to match that region of my mind. Camelot.” (p. 15)

- “I thought the mail strike may be over.” (p. 91)

Synthesising task/activity

Task One: Developing a paragraph

Have students:

- Do a close reading of the passage on page 87 from “Una Porteous walked about the house . . . ” where Colin Porteous announces he wants a divorce. Annotate the passage to:

a) demonstrate the emerging strength of Nora Porteous as the Depression concludes and her desire to enter the world of dressmaking rises

b) highlight the setting of her figurative “bird cage” under Una Porteous’ roof comment on the prose style of Anderson’s writing at this important stage of Nora’s development. - Write a paragraph synthesising their findings in which they argue how character, setting and style combine to convey the themes of the novel.

OR

Task 2: Visual representation of the social and historical context in Anderson’s novel

Using some medium of visual representation, students construct a three – minute tableau of the significant social, historical, literary, political and psychological influences referenced in the novel. They could:

- provide a relevant quotation from the text and

- a symbolic representation of event or movement.

OR

Task 3

Using the work done on the structure of the novel and the nature of memory, the students write an extended response to the question:

- How does Anderson use metaphor to explore the problems with memory and time? In your response, refer to the representation of the significant events in Nora’s life and analyse Anderson’s use of language techniques to explore these central moments.

(ACELR057) (ACELR058) (ACELR065)

Context

Historical context

Tirra Lirra by the River was written in 1978 about a woman whose life experiences spanned the most important events of the 20th century, shaping the attitudes of that time.

Students should consider the influence in the novel of the First World War, the Great Depression, the Second World War, the mail strike, communism and psycho-analysis. The following quotations could serve as a starting point:

- “And I would probably have said, yes, of course, because in these times, when sexuality is so very fashionable, it is easy to believe that it underlies all our actions. But really, though I am quite aware of the sexual nature of the incident. I don’t believe I was looking for a lover. Or not only for a lover. I believe I was also trying to match that region of my mind. Camelot.” (p. 15)

- “I no longer thought of Sir Lancelot. The war, and the boys under the camphor laurels, had obliterated him.” (p. 23)

- “The Depression was over . . . Three months after I had begun to earn money, Colin came home with a girl. ‘This is Pearl,” he said.” (p. 87)

- “I thought the mail strike may be over.” (p. 91)

- “Whenever I think of communism I see something grey.” (p. 115)

- “The winter of 1939-1940 was extremely severe. Every time I got on my feet, down I would go again, to lie in bed coughing.” (p. 126).

Students should also research Second Wave Feminism and examine the extent to whichTirra Lirra by the River could be read as feminist literature. As part of this examination they should consider:

- Nora’s quest for social and economic independence and self actualisation;

- the choice of Nora as the name of the narrator, recalling the protagonist of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House;

- a comparison of the cover of the 1997 Picador edition of the novel with the iconic 1970 cover of The Female Eunuch designed by John Holmes.

Literary Context

Intertextuality

Jessica Anderson’s novel draws strongly on Tennyson’s poem, ‘The Lady of Shallot‘ for inspiration, extended metaphor and intertextuality. Read the original text with students and view some of the paintings inspired by it, particularly by painter William Waterhouse who had a series of paintings based on the poem:

- William Waterhouse The Lady of Shalott

- Waterhouse The Lady of Shallot (I am Half-Sick of Shadows)

- Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott looking at Lancelot

- William Hunt and Robert Edward The Lady of Shalott

On page 12, we have the straight-forward reference to Tennyson’s poem in the depiction of Nora’s early poetry reading and fascination with Camelot – an inner world which drew her into a “spell” wherein “landscape had become a part of (her) mind”. This inclusion foreshadows an extended metaphor of Camelot, the life of Lady Shallot and inter-textuality with Tennyson’s verse itself.

Consider the similarities between the Tennyson poem and Anderson’s novel via its thematic content alone. The opening lines from Tennyson offer:

On either side the river lie

Long fields of barley and of rye,

That clothe the wold and meet the sky

We are drawn into abstract consideration that one of the principal conceits of Anderson’s text is the way that Nora, the dressmaker, perceives the world as one clothed in nature. For reference to this idea, review Nora’s Keats-like immersion in nature on page 14 when she lets herself “roll into one of these clefts”. Look also at pages 198 and 199 when Nora belatedly returns to her childhood river and is lost in the modern landscape of houses, cars and swimming pools, and afterwards reminisces with Jack Cust about the way that the former residents grew flowers (larkspurs, hollyhocks, candytuft, columbines and pinks), with the inference that they employed nature to clothe the world as she too clothed it in dress material.

Four grey walls, and four grey towers,

Overlook a space of flowers,

And the silent isle imbowers

The Lady of Shalott.

Next consider the reference on page 52 to the four houses in Potts Point where Nora resides in the earliest phase of her marriage with Colin Porteous (Bomrea, Tarana, Crecy and Agincourt). The reference to “four grey walls” in the Anderson text is perhaps more reminiscent of Nora’s five lonely years living under Una Porteous’ roof with her husband and the metaphorical entrapment she experienced in that place – a room which overlooked a single lemon tree.

By the margin, willow veil’d,

Slide the heavy barges trail’d

By slow horses

The third stanza of the Tennyson poem conveys a subconscious memory of Nora for her father’s funeral (“by slow horses”), and thereby a symbolic representation of the way that Nora’s life memories are conjoined in verse via a beautifully rendered line in Anderson’s prose: “The poetry in my head was like a jumble of broken jewellery.”

There she weaves by night and day

A magic web with colours gay

We remember that Nora is a dressmaker and an embroiderer of note, and that the latter activity is drawn upon in extended metaphor as a way to depict Nora re-imagining of the past.

A curse is on her if she stay

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be,

And so she weaveth steadily,

And little other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott

A central theme of the early pages is Nora’s unwillingness to stay in her childhood home and her desire to journey somewhere else – anywhere else but where she lives. Her Camelot is initially Sydney, and later London. Dressmaking and embroidery are Nora’s way of immersing herself in, and expressing the intricate patterns and designs of her inner life without revealing her thoughts to others. She is essentially an introverted and lonely character who does not share the innermost detail of her life during her friendships with Olive Partridge and Ida Mayo, nor with her sister Grace. Later, her correspondence with Hilda and Liza deteriorates for the lack of honest and immediate conversation.

And moving thro’ a mirror clear

That hangs before her all the year,

Shadows of the world appear.

While Anderson avoids too literal a comparison with Tennyson’s text by avoiding the subject or imagery of mirrors, Nora’s own “shadows of the world appear” via the globe metaphorically suspended on her head – a surface “inscribed with thousands of images” which will turn occasionally after an accidental flick; she doesn’t mind “inspecting some of the dark patches now and again.”

In many ways, it is more beneficial for students to study this non-literal comparison in Tennyson and Anderson’s text for the way that it compels them to study the inner realm of its metaphorical meaning. In Tennyson’s text, the mirror may be said to represent Lady Shallot’s desire to engage in an abstract world devoid of three-dimensional images, which consequently removes her from the demands of physical and emotional intimacy, whereas in Anderson’s text Nora’s ‘globe’ is a form of self-control and emotional repression; she hides away her affective response to personal rejection and pain in a life-long, self-conceit that if a memory is deposited on the other side of her “globe” that it doesn’t actually exist in reality.

Sometimes a troop of damsels glad,

An abbot on an ambling pad,

Sometimes a curly shepherd-lad,

Or long-hair’d page in crimson clad,

Goes by to tower’d Camelot;

And sometimes thro’ the mirror blue

The knights come riding two and two:

She hath no loyal knight and true,

The Lady of Shalott.

Almost every aspect of this stanza is represented in Anderson’s novel: “a troop of damsels glad” in her friendship at number six with Hilda and Liza; “the abbot on an ambling pad” (p. 17) with the clergyman of “mechanical piety” who delivered sermons in the little timber church smelling of coconut oil; the curly shepherd-lad referenced directly in Arch Cust and his annoying, sexually-frustrating, teenage seduction at Cust’s newsagent; “the long-hair’d page in crimson clad” reminding strongly of Lewie Johns at Bomera draping himself in Ida Mayo’s cloth; and finally “the knights come riding two and two” evoking the unusual similarity and uncanny disappearance act of Colin and John Porteous (p. 48) – remembering that in Colin Porteous, Nora “hath no loyal knight and true”.

But in her web she still delights

To weave the mirror’s magic sights,

For often thro’ the silent nights

A funeral, with plumes and lights

And music, went to Camelot:

Or when the moon was overhead,

Came two young lovers lately wed:

“I am half sick of shadows,” said

The Lady of Shalott.

This particular stanza in the Tennyson poem directly links to the subject matter of Nora’s years in London as a theatrical dress-maker, and thematically to her way of immersing herself in a theatrical life of light and shadow (without actually participating on an emotional level) after her suicide attempt. The “funeral, with plumes and lights” is the thing itself – the buried memory of her father’s funeral – which resurfaces on the novel’s final page. Finally, Lady Shallot’s despair at shadows is reflected in Nora’s desire to abandon her self-repression and to bring Colin Porteous and her father fully into the light in the third act of her life.

His broad clear brow in sunlight glow’d;

On burnish’d hooves his war-horse trode;

From underneath his helmet flow’d

His coal-black curls as on he rode,

As he rode down to Camelot.

From the bank and from the river

He flash’d into the crystal mirror,

“Tirra lirra,” by the river

Sang Sir Lancelot.

Here we have an ironic image of Sir Lancelot in Anderson’s text as her dead father – a direct reference to the title of the novel – and a symbolic sense that Nora’s Camelot is effectively a region of her mind where she may communion strongly with her father’s memory without literally crossing over to join him in death.

- Once Nora discovers the river – “the real river” – why does she then discover her Camelot? Why is it that she only remembers her father’s funeral upon reaching the river?

- How does this narrative device further link the novel to the Tennyson poem?

Extra Reading

Students might consider this discussion about the links between Tirra Lirra by the Riverand ‘The Lady of Shallot’: Farewell Jessica Anderson (1916-2010) by Jane Gleeson-White in ‘Overland 60′.

Aspects of genre

Anderson’s text draws upon several genres:

- twentieth century Australian fiction (reminding strongly of George Johnston’s trilogy of semi-autobiographical novels which similarly deal with the experiences of an expatriate Australian)

- Romantic poetry (principally that of the plainly-written Wordsworth verse)

- early modernist writing (reminding strongly of Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthousewhich similarly deals with a simple journey that results in a flood of memories – metaphorised in Anderson’s text as the “inundation” of Nora’s pneumonia).

All three genres might be considered a comparison to Anderson’s text in their antecedent and aforementioned source.

The text as representative of Australian culture

The Australian Novel

It would be useful to begin a discussion about the nature of an Australian text. Students can read and complete activities on pages 7-13 of Studying the Australian Novel in Senior English Classes.

The following questions might be asked of the class:

- What is the purpose of having a national literature?

- Is there such a thing as an “Australian perspective” on the world? What informs that perspective?

- What is the function of an Australian novel? Is it to put forward a particular political or moral view? Or is it to explore artistically what it means to be Australian?

- To what extent can an Australian novel draw upon world literature for its inspiration and ideas and still remain distinctively Australian?

- Is there even such a thing as a typical Australian novel? If so, what are it s conventions?

Tirra Lirra by the River as an Australian novel

To what extent could Anderson’s female protagonist be seen as:

- a representation in extended metaphor of the Australian culture at large?Is Nora Porteous’s artistic expression emblematic of her own country’s nascent culture in the mid-twentieth century?

- akin to the young Australian nation striving for a ‘place in the world’ following the convict experiment and the lost early years of federation? Does Nora’s loss of loving support through the death of her father and abandonment by her husband parallel Australia’s abandonment by Britain and the consequent search for a new national identity?

- a representative of a post-colonial writing back to the centre? In her Queensland setting, Nora’s imagination is awakened by English poetry, particularly Idylls of the King but her search for Camelot only ends when she returns home to her own river.

Tirra Lirra by the River was a winner of the Miles Franklin Literary Award for Australian Literature. The conditions for receiving the award include that: “[the] prize shall be awarded for the Novel for the year which is of the highest literary merit and which must present Australian Life in any of its phases . . .”

- Why would this book qualify for the Miles Franklin Literary Award?

- To what extent do you agree with Geordie Williamson’s analysis (Interview: Finding Australia’s lost classics) that Tirra Lirra by the River is a canonical text and inspirational to later Australian writers?

Rich assessment tasks

Creative writing task

The students select a poem that speaks to them personally and, using quotations or references from it, write about an aspect of life experience.

OR

A judge’s report for the Miles Franklin Literary Award

Have students watch the Video on the Miles Franklin judges page to see what is valued and write a judge’s report on the novel explaining why it should be awarded the Miles Franklin Award.

(ACELR055) (ACELR058) (ACELR066)

Synthesise Core Ideas

Justifying any revisions to the initial response

Draw students into a discussion about the way that the novel has subverted their narrative expectations.

- To what degree does Nora Roche fulfil or challenge our expectations about the narrative arc of an “older woman”?

- Is it realistic that a person approaching the end of their life would seek to examine the shadows which they have hitherto blocked from their minds? To what extent has Anderson been successful in fulfilling our expectations about the revelatory quality of these shadows?

Students can watch this video (Texts in the city: The Wheeler Centre; Rosalie Ham on Tirra Lirra by the River) and consider how the speaker has re-evaluated her views on Tirra Lirra by the River.

- How does Rosalie perceive the connection between Nora, Dorothy Rainbow and Lady Shallot? Is it a valid argument?

- How does Rosalie evaluate the treatment of memory in the text via Nora’s “globe”?

- What makes Rosalie impatient with Nora?

- What does this say about the reader’s relationship with the text itself?

Rich assessment task

Instructions to students:

Task: Write and deliver a pitch for a TV show centred on Jessica Anderson

Context: A series of shows on important Australian writers and great Australian novels

Audience: Students of literature and an interested educated Australian public

For this task you have to recommend that Jessica Anderson is a great Australian writer who should be included in a program on great Australian writers.

The pitch needs to:

- Justify Jessica Anderson’s place as a great Australian novelist – this may include reviews and critics comments about her.

- Focus on one novel (Tirra Lirra) as an illustration of her skill as a novelist.

- Outline the structure of the show – will it start with biography? Critical comment? Quotations? Illustrations? Propose what will go into the program under a series of subheadings.

It will be delivered to the class as a speech.

OR

Task: Write and deliver a pitch for a TV show centred on Nora Roche

Context: The show Australian Story on ABC TV

Audience: General Australian public

For this task you have to enter the world of Nora and imagine her career as a dressmaker.

The pitch needs to:

- Justify Nora’s place as an interesting Australian.

- Focus on her achievements but show what she struggled against.

- Outline the structure of the show – will it start with biography? anecdotes?

- Propose what will go into the program under a series of subheadings.

It will be delivered to the class as a speech.

(ACELR055) (ACELR058) (ACELR060) (ACELR068)