Connecting to prior knowledge

Multiple perspectives

Introduce the idea of multiple perspectives to the class through a discussion. Record their ideas from a brainstorm session about what they understand about this concept.

Before beginning, discuss how turn-taking looks/feels and how it differs from formal presentations (like show and tell) and playground banter. Ask the students what words they can use to disagree with respect, e.g. ‘I heard you say _____ but my experience is different.’

Pair and post-it

Explain that identifying multiple perspectives is about seeing different points of view. This can be true of artworks as well – display portraits or paintings that utilise optical illusions for the class. There are also a range of books in the More Resources section that utilise this form of illustration.

Have students pair up and then allocate each pair an artwork from one of the websites or books. Provide each student with different coloured sticky notes and ask them to record their perspectives for the allocated illustration. Remind them that their job is to find two different perspectives on the one illustration. Have each pair present their findings to another pair.

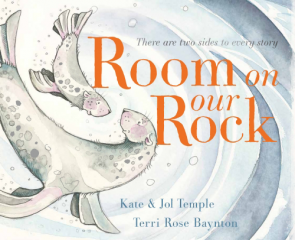

Introduce the book Room on our Rock to the students. Emphasise the quote on the cover: ‘There are two sides to every story’. Discuss what this might mean in light of the previous investigation with illusion illustrations. Show students how the front and back covers of the book are the same. There isn’t a blurb on the back that suggests what this book is about. Instead, the flap at the front of the book provides a provocation for consideration:

Two seals are perched on a rock. When others need shelter, do they share it?

Share ideas about what the two sides of the story might be. Read the book from front to back, and then back to front.

Exploring the text in context of our community, school and ‘me’

Explain that the authors, Kate and Jol Temple, have used the reverse poetry format to provide two different versions of the one story. Elaborate on the idea that a reverse poem has one meaning when read forward and the opposite meaning when read backwards. Reverse poetry is known by many different names: mirror poetry, palindrome poetry and shadow poetry. Discuss these terms and what they mean.

Reread Room on our Rock. Discuss what this book could be about. Explain what a theme is and discuss the themes in this book. Record these for display in your learning space. Point out the front and back covers and how they are mirror images of each other.

Provide a range of picture books that also deal with refugees, homelessness, bullying and displacement. Have students work in small groups to read through one or two of the books and gather more information about refugees.

To assist the students to read for a purpose, pose some questions such as:

- How are the refugees treated?

- How do the refugees try to reach out for help?

Books could include any of the following – select titles that suit your context:

- Goat on a Boat by Nick Dent and Suzanne Houghton

- Wisp: A Story of Hope by Zana Fraillon and Grahame Baker-Smith

- Waves* by Donna Rawlins, Heather Potter and Mark Jackson

- The Arrival* by Shaun Tan

- The Little Refugee* by Anh Do, Suzanne Do and Bruce Whatley

- Teacup* by Rebecca Young and Mark Ottley

- Stepping Stones: A Refugee Family’s Journey by Margriet Ruurs, Nizar Ali Badr, and Falah Raheem

- My Name is not Refugee by Kate Milner

- My Two Blankets* by Irena Kobald and Freya Blackwood

- The Treasure Box* by Margaret Wild and Freya Blackwood

- A Different Pond by Bao Phi

- Four Feet, Two Sandals by Karen Lynn Williams and Khadra Mohammed

- Refugees* by David Miller

- The Suitcase by Chris Naylor-Ballesteros

- Fly Away Home by Eve Bunting and Ronald Himler

- Llama Llama and the Bully Goat by Anna Dewdney

- Marlene, Marlene, Queen of Mean by Jane Lynch

- Wonder by R. J. Palacio

* Reading Australia title

Then ask students to select a character and act out what they experienced in one of the books. This can be done through you reading to the class and a pair of students taking on key roles, or by students acting out the characters’ experiences simultaneously (perhaps outdoors or in the school hall). If you choose the first option, this could be completed over many days.

Rich assessment task

Discovering your ‘so what?’

Ask students to recall what they discovered in their research, book investigations and role-plays that resonated with them. Can they identify an ‘aha!’ or ‘so what?’ moment? What do they have to say about this topic that hasn’t been said in Room on our Rock or the other books they have read?

Ask students to craft a response about what is important to them and what they would like to share with others. Prompts could include:

- What do you think you bring to this topic? What do you know about this topic?

- What was something new you learned about this topic from reading the books and listening to others share their ideas?

- What would you like to tell others about this topic?

- What hasn’t been said and needs to be said?

- Ask yourself ‘so what?’ and decide on what you or others could do about this situation.

Responding to the text

So what… now what?

Listen to the ABC Radio National interview with Kate and Jol Temple. Discuss what they identified as an issue worth addressing in their book. Consider the themes suggested, included sharing, the world we live in and displacement. Reconciliation in the Australian context might also be included.

Revisit the previous Rich Assessment Task where students identified an issue that was important to them. Discuss how there were a range of different responses, as issues resonate with everyone differently. Sometimes this is due to a personal connection, an understanding of what is happening, or curiosity about an issue. Put students in small groups so that they can share and hear about different perspectives on the same or similar issues (ensure that there has been a discussion about valuing all opinions in this safe environment beforehand). Suggest that this is an opportunity to gather different ideas and perspectives about the area they have identified for further consideration: their ‘so what?’ investigation.

After the small group discussions, have students complete an ‘I know, I feel, I wonder’ (PDF, 80KB) chart to record their understanding and questions.

Exploring plot, character, setting and theme

Exploring conflicts

Reread Room on our Rock. Within this story there is a conflict in the first (forward) reading of the book. Discuss with students that there are different types of conflicts:

- person vs self

- person vs person

- person vs nature

- person vs society

Create a large grid and brainstorm a range of examples for each type of conflict:

| Person vs self | Person vs person |

|

|

| Person vs nature | Person vs society |

|

|

Then create another grid, using the same headings, and list the titles of books you are reading in class for this unit so that students can see there is some form of conflict in most stories. See the More Resources section at the bottom of this page for some suggested books.

Knowing me, knowing you

Reread Room on our Rock (forwards) asking the students to pay particular attention to the illustrations. Ask students to consider:

- Do the seals’ external actions mirror their internal thinking?

- Is there a place in the book where one of the seals is saying something but the words don’t match their actions?

- Are there any clues to the true intentions of the seals?

Have the students draw a scene from the book and add in thought bubbles that demonstrate what the seals might be thinking at this point in the story. Remind students of the background knowledge they have about sharing, refugees, displacement, etc. from class discussions. Model, using think alouds, how to craft a response.

Reread Room on our Rock (backwards) and ask the same questions. Engage in the same task, with students recording what the seals might be thinking as the story is read again.

Discuss how the authors and illustrator might have worked together to create scenes that can be read in different ways. There are some thoughts on this in the aforementioned interview.

(AC9E3LE01) (AC9E3LE03) (AC9E3LY05)

Rich assessment task

Engage in a brief discussion of the terms ‘literal’ and ‘inferred’ meaning. Ask the students if they can identify how the text structure or language features shift the meaning. For example, ‘There’s no room on our rock’ – the word ‘no’ is so definitive, it’s not allowing any other option.

Ask students to present the two sides to their issue by drawing thought bubbles that illustrate multiple perspectives. This can be done by folding a page in half and drawing the bubbles, or by using the provided template (PDF, 90KB).

Examining text structure and organisation

Repeating imagery

Reread Room on our Rock and ask students to look for something that repeats throughout the book – from the cover and front matter, across the pages, through to the end papers and back cover. Is there an object, person, setting or image that is repeated throughout the story?

Support the discussion by asking a range of questions such as:

- What is repeating throughout the book?

- What could that object/feature mean or represent?

- What is the importance of this object or feature?

- What are you wondering about?

Throughout the book, movement is emphasised through swirling water, crashing waves, moving currents and bubbles in the water. Discuss how this is not just a setting, but also a feeling that is created. Explore the visual features in this book, creating a class chart of what you discover. Additional information about visual literacy features can be found here.

Examining grammar and vocabulary

Purpose of a sentence

Write out the text from the story so that students can see it in its entirety. You can also view the story here.

Look at the phrases that help the poem make sense in both directions. These lines are used to link together the authors’ statements or position, and when read in reverse, the opinion changes. Highlight the phrases that take on this function in the text:

- ‘So it’s ridiculous to say’

- ‘You’ll never hear us say’

- ‘You know you can’t’

- ‘As you can plainly see’

Discuss how these phrases are not related to the issue but add to the impact of the statement.

Investigate other reverse poems (select appropriate examples) and identify phrases that take on this role. There are also several books based on this style of poetry listed in the More Resources section. Add to the collection of phrases in a class chart. This could include the following:

- I refuse to believe that…

- I believe that…

- What if…

- Tell yourself that…

- Always remember that…

- It is true that…

- It is not true that…

- How can people say that…

- Don’t forget that…

- Always remember that…

- Never let anyone tell you that…

- No one is…

- Everyone is…

- It is clear that…

- Everyone knows that…

- I will always say…

- I will never say…

Select one of the phrases and then model how it can be used in a three-line poem that can be reversed. For example:

My brother is annoying.

Never let anyone tell you that

Brothers are ace!

As a class, generate success criteria for writing a reverse poem. Ask the students to annotate the example so that the required elements are clearly articulated and visualised.

Rich assessment task

Have students select one of the above phrases and craft a three-line poem that can be reversed. This poem can be about something familiar to them, but still focused on a social justice issue.

After crafting their poem, students can use a cooperative learning technique to share their writing. This could include:

Follow up by inviting students to publish their poem in a chosen format (class book, digitally, etc.).

Topic – question – statement

Ask students to revisit the issue they connected with earlier in the teaching sequence. Divide a page in half and have students list all the questions or wonderings they and their peers may have about the topic. Then, on the other side of the page, turn these questions into statements that could be added to a reverse poem. For example:

| Question | Statement |

| Why don’t all children get the food they need to survive? | Children do not get a meal every day. |

| Why does bullying happen? | Bullying happens in schools. |

| Why doesn’t everyone have a home to live in? | Homelessness can happen to anyone. |

Who’s your audience?

Before students begin to craft their own reverse prose, have them think about who their audience will be. This task will focus on writing to both entertain and persuade as students present their issue through two perspectives.

Prompts could include:

- Who will read your story?

- What message do you want them to hear?

- What two sides of the story will you present to the audience?

- What language will they read?

- What words or phrases will you use?

- When your story has been read forwards and backwards what will be the ‘takeaway’ for the reader?

Telling through titles

Revisit the class chart you created (under Responding) to demonstrate the different types of conflicts in books. Focus the discussion on the books that represented conflict between people and society. Look at the titles in this collection and discuss how often the title gives a clue to the issue or conflict, without completely revealing it.

Reread Room on our Rock and discuss how the title connects to multiple aspects of the book: setting, characters and theme. Alternatively, watch a reading on Vimeo.

Storyboard plan

Use a storyboard template or an online app so that students can plan the story they would like to tell (text and illustrations) based on their identified issue or conflict. The short story should meet the following success criteria:

- it can be read both forwards and backwards and make sense

- it is about an issue or conflict

- it presents two different perspectives on one issue or conflict

- the illustrations match the text

Rich assessment task

Using their storyboard plan and notes from previous learning experiences, students complete their reverse short story by making a book through an online book creator app.

Once completed, students then self-assess their work using the success criteria created in the previous activity.