Essay by Mark Isaacs

Just Macbeth! is Shakespeare like I’ve never read him before. It’s raucous and disgusting, immature and absurd. Kings sing karaoke, there is a time-travel potion made from dog saliva, and children plot regicide for Wizz Fizz rewards. What makes Shakespeare’s collection of works timeless is its ability to be reinterpreted across mediums, regardless of era, culture or language. Macbeth is no different, having been famously reworked countless times. But never have I read the script adapted for a younger audience to include fart jokes and bedwetting. Many Australians may have never read anything written by Shakespeare, let alone seen one of his plays. This book aims to persuade children that they should. While it could easily be seen as cringe-worthy toilet humour, there is a method to the madness (note the Hamlet reference) of Just Macbeth!. Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton’s interpretation manages to disguise learning as a good time. A really good time.

You know I love Shakespeare. And when I say I love Shakespeare, I don’t just mean I love Shakespeare, I mean I REALLY love Shakespeare. (p. 1)

Writer Andy Griffiths and illustrator Terry Denton created the Just! series in 1997, and it has now sold over two million copies worldwide. If you weren’t aware that there was a Just! series before reading this book, it doesn’t take long to figure out: there are numerous references throughout to other books in the series, such as on pages 49 and 69, and twice on 136. Cheeky advertisements can be found in the margins, such as ‘Learn about more girl germs, see Just Shocking! p85’ (p. 11). Griffiths and his wife, Jill, were commissioned by theatre company Bell Shakespeare in 2005 to adapt Macbeth for a younger audience. Just Macbeth! was worked into a script for the critically acclaimed production by director Wayne Harrison, which premiered in Melbourne in 2008. In 2009, that script was turned into a book by Griffiths and Denton.

The story begins at Andy’s house – in his kitchen, ‘to be exact’ (p. 2). Andy, his best friend Danny, and Andy’s romantic interest, Lisa Mackney, are studying the play, Macbeth, for school. Their teacher, Ms Livingstone, has split up the class into groups and each group has been assigned a scene to perform. Andy, Danny and Lisa have been appointed ‘the scene where three witches put all these really horrible-sounding things into a cauldron and say a spell’ (p. 2). After mixing as many of the ingredients as they can find (no spleen of a blaspheming boy, and dog saliva rather than dog tongue – much to Lisa’s disappointment) in Andy’s mum’s food processor, the three of them dare each other to drink the concoction.

As it turns out, they really did make a magic potion, and it transports them to a medieval battle scene in Scotland (and one of the opening scenes of Macbeth). Three bearded witches address Andy as Macbeth and Danny as Banquo, and the boys believe that they’ve been mistaken as warriors and thanes. The witches then deliver the prophecy that Macbeth will become king, setting the dramatic wheel in motion. From here the story is loosely based around the original Macbeth plot, with modern adaptations to keep the script in the style of the Just! series and accessible for younger audiences.

Jealousy and suspicion taint the relationship between Andy (Macbeth) and Danny (Banquo), which is only made worse when they learn Andy has a castle and a wife, whom we later discover is Lisa Mackney. Even though the language and plot have been simplified, it’s still a story of power and ambition. Lisa convinces Andy that in order to fulfil the bearded witches’ regal prophecy they will have to kill King Duncan. After a wild night of karaoke and a comic strip illustration, Andy murders the sleeping king.

Andy and Lisa become obsessed with the prophecy and decide to kill off Danny (Banquo) and whoever else stands in their path to the crown. Griffith and Denton do not avoid contentious topics such as insanity and murder; in fact, they revel in them. Both Macbeth and Lady Macbeth’s descent into madness is mocked, and Andy uses a ‘mashing and pulverising machine’ (p. 143) to kill his enemies, including all of Macduff the Gnome’s kittens, puppies and ponies.

Andy learns that he should never have trusted in the prophecies of the bearded witches when Birnam Wood comes to Dunsinane with his enemy, Macduff, and an army of ten thousand English garden gnomes (you can learn about why Andy hates garden gnomes in Just Annoying!, on page 34). In the pandemonium of the imminent battle (best expressed by Denton’s illustrations), Lisa dies (although there is no mention of suicide like in the original script). The last of the prophecies to fool Andy, that no man born of woman shall kill him, sees Macduff explain to Andy what a caesarean section is, just before cutting his head off. In the final chapter, we learn that their time travel to Scotland was all a dream.

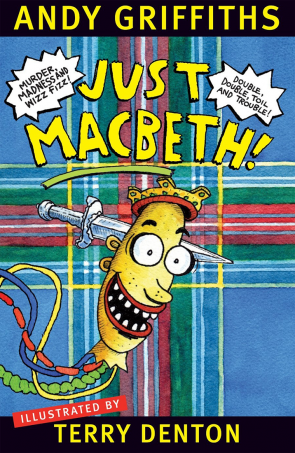

Griffiths and Denton do their utmost to reach a younger audience with Just Macbeth! – and they succeed. The style is established early (as early as is possible really): the front cover is emblazoned with a beheaded Macbeth, a dagger behind his head and colourful, ribbon-like entrails coming out of his neck. The tartan background provides a clue to the Scottish origins of the play, and the comic book-style puff quotes predict ‘murder, madness and Wizz Fizz!’.

The book is peppered with Denton’s absurd illustrations: Shakespeare’s head hangs around the page numbers, prattling on; a man tries to pull a sword from a stone for 198 pages; there are instructions on how to squirrel grip (seriously); and much more. At times the drawings advance the narrative, such as when they travel through time via a three-page spread (p. 23–25); other times they can be educational and teach us what a spleen is; but more often than not they bear no relevance to the play, such as the Amazing Eye Trick #472 on page 2. There are advantages and disadvantages to this: Denton’s doodling in the margins prevents students from doing it themselves, but it can be distracting, sending you back and forth through the book looking for instructions on ‘how to painlessly cut off your dog’s tongue’ or reading about the ‘great gnomes of history’ series. Having said that, I’m a big fan of the illustrations, which frequently made me laugh out loud. They give the book an anarchic edge in the vein of Monty Python, and ensure it can be an enjoyable read.

Just Macbeth! is structured as part narrative, part theatre script. There are stage directions and scripted lines, but acts and scenes are replaced by book chapters. And Griffiths’ stage directions are more descriptive than they might normally be, as a way of making it easier to follow the action or the emotion in the scenes:

Lennox: [confused] Who’s Andy? And who’s Lisa?

Andy: [aside to Danny] Don’t keep using our real names – he’ll get suspicious.

[Lennox looks suspiciously at them]

There are benefits to straddling the two worlds. For those readers who are unfamiliar with theatre scripts, this style acts as a gateway into the more complex and daunting script structure. In addition, Griffiths and Denton’s format eases the reader into Shakespearean English. The first few times Shakespeare is quoted directly, an explanation is written into the script:

Duncan: Only I have left to say, more is thy due than more than all can pay.

Andy: Are you saying you can’t pay me?

Duncan: No, I’m merely saying that I owe you much more than I can possibly pay you. (p. 61)

By chapter twelve, much of the script is written in Shakespeare’s original lines. The protagonists all have a go at performing soliloquies, which start un-theatrically – ‘At last! My turn for a soliloquy!’ (p. 5) – but improve throughout the book until the entirety of chapter five is a proper Shakespearean soliloquy from Andy. In this way, Just Macbeth! makes a difficult text easy to read.

Numerous language techniques are used in the book, including the ‘heaps cool’ colloquialisms and the millions of examples of hyperbole. Unfortunately, this means the script loses some of its Shakespearean edge. Shakespeare was a poet before he was a playwright; he adapted his poetic style and use of the iambic pentameter to work with traditional theatre-writing and language. By interrupting that style we lose some of the beauty of his writing.

This being said, such appropriation is useful for educators trying to work out new ways to engage young students in traditional texts. For the most part, Griffiths and Denton have managed to splice the old and new effectively. What’s more, the playfulness of form and language they employ is quite appropriate when you consider Shakespeare was a master at creating words and modifying language to tell his stories.

Educational lessons are disguised amongst jokes and teenage bickering. This can be humorous, but it can also get tiresome. A good example is on page 5, where Lisa explains to Andy and Danny that women were forbidden to act in Shakespeare’s time; not long after, the conversation dissolves into an argument about boys’ and girls’ germs. This type of dialogue is shamelessly immature, but evidently this is the point as a means of engaging younger readers.

When you look past the absurdity of the writing and illustrations, there is great value in the way Just Macbeth! simplifies and re-interprets complex themes, story arcs, and characters and their relationships. For example, the text explores the multiple motivations that underpin Macbeth and Lady Macbeth’s ambition. In this interpretation, Andy is initially driven by his desire to impress Lisa – ‘the most beautiful girl in the world’ – and Lisa is driven by her ambition to be class captain. As Lady Macbeth, that ambition is magnified: she wants to be queen. ‘Don’t you want to make me happy? Because that’s what you’re supposed to do now that we are married,’ says Lisa, persuading Andy to commit dark deeds.

There’s a degree of gender stereotyping in this, but as the story progresses other contributing factors to Andy’s despotism are introduced, such as his obsession with the prophecy set by the witches and his descent into madness. By the end of the book, Lisa argues that her ambition and her words didn’t force Macbeth to become a tyrant; that was a choice he willingly made.

Danny: Yeah, talk about a ruthless killer! You were completely out of control.

Andy: Ruthless killer? Lisa started! Killing the King was her idea! She told me to do it and when I said no she called me a chicken! She’s an accomplice!

Lisa: Just because I tell you to do something doesn’t mean you have to do it. (p. 190)

The simplicity of this argument leads to some key questions in Shakespeare’s play. How influential was Lady Macbeth in turning Macbeth into a tyrant? Was he driven by her ambition or his own? Was he motivated by the witches’ prophecy or was that merely a spark to dry tinder? In a soliloquy before his gruesome death, Andy tells the reader that he learned ‘not to listen to witches, not to listen to my wife, not to ignore my conscience’ (p. 187).

Despite simplifying and reworking the text, Griffiths and Denton manage to explore key themes of the script, which provide a doorway into the wonderful world of Shakespeare.

References

Shakespeare, W 2009, Macbeth, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Further Reading

Bryson, B 2007, Shakespeare: The World as a Stage, Harper Press

No Sweat Shakespeare, <http://www.nosweatshakespeare.com/>.

Shakespeare (mobile app), Playshakespeare.com, <https://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/shakespeare/id285035416?mt=8>.

© Copyright Mark Isaacs 2016