Essay by Catherine Cole

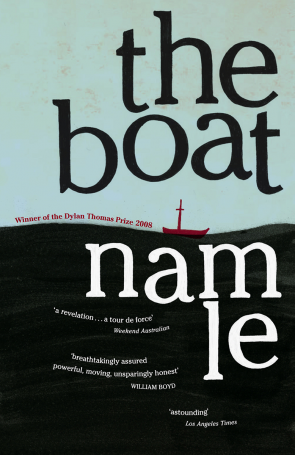

Nam Le’s The Boat is one of the most impressive short story collections published during the past decade. Critics have hailed it as ‘a singular masterpiece’ (Kakutani 2008), ‘ambitious and confident’ (Penner 2008) and ‘heartrending’ (Pincus 2008). It has been compared to seminal short story collections such as James Joyce’s Dubliners. Like Joyce’s collection (all its stories set in Dublin), The Boat is both specific about place and universal in the manner in which it offers new ways of seeing the world through perfectly shaped stories that seem to hold truth within them. This is certainly due to the unity of the collection, which while offering diversity in each story also creates a kind of ‘story cycle’ which propels the collection’s momentum, but also because of Le’s writing and its exquisite capturing of the human condition through the fragile encounters between the stories’ characters.

The Boat also offers a new conversation about the Vietnam War and its aftermath. The collection encompasses a diverse geography, from Iran to Colombia, the United States to Australia, Japan and the South China Sea, yet the Vietnam War is an assertive presence too in the collection’s first and last stories, ‘Love and Honour and Pity and Pride and Compassion and Sacrifice’ and ‘The Boat’. These two stories encircle the collection as one might cup or protect something — two stories with inescapable references to the author’s personal and political history.

For many Australians, Vietnam was discovered through a series of images: conscripted young Australian soldiers or ‘nasho’s’, napalm, burning villages, massacres, Vietnamese people desperately fleeing the advancing communists, and refugees in boats. This was a war captured on TV and in print like no other war before it. In many ways Vietnam will always be thought of as a young person’s war, not in the same way that the youthful dead of WWI are remembered through ceremonies in northern France and Gallipoli each ANZAC Day, but through the impact of the war on the youth of Vietnam and Australia and the controversy and protest which resulted from the conflict. By the time Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War ended in 1975, five hundred and twenty Australians had died and over three million Vietnamese. Our soldiers returned to hostility or indifference. Vietnamese people such as Nam Le’s parents, fearful of what lay ahead for them and their country, fled in any way they could, often in crowded boats through treacherous seas. By then, Vietnam had been seared onto Australia’s national consciousness. The relationship between our two countries has continued to evolve but remains paradoxical. Today we are friends, yet we are still caught in one another’s histories.

Vietnam offers a site of contradictions, of loss and nostalgia — a lost homeland, a place of a soldier’s lost youth and innocence, a place of lost ideals, a site of continuous contestation about the rights and wrongs of history, and a place of lost époques (or new ones, for tourists). All this from a country which, to paraphrase the American-Vietnamese writer Andrew Lam, has been described as a fourth rate power. For the first time in American — and Australian — history, we would be haunted by unanswerable questions, confronted by a tragic ending, a war lost (Lam page 95).

While Nam Le gives reference to his parent’s struggle through The Boat’s opening and closing narratives, most of the stories seem completely unrelated to Vietnam. These are the works of a writer who can establish his connection with his parents’ past lives while announcing himself a writer of a very different world. The author, Christopher Lee, sees the collection’s first story, ‘Love and Honour and Pity and Pride and Compassion and Sacrifice’ as ‘a remarkable meditation on the meaning of “ethnic writing”‘ (Lee page 32) and Nam Le has admitted in interviews that he has avoided the label of ‘ethnic writer’ while at the same time acknowledging that his relationship with Vietnam is a complex one. ‘For a long time,’ he says,

I vowed I wouldn’t fall into writing ethnic stories, immigrant stories . . . Then I realised that not only was I working against these expectations (market, self, literary, cultural), I was working against my knee-jerk resistance to such expectations. How I see it now is no matter what or where I write about, I feel a responsibility to the subject matter. Not so much to get it right as to do it justice. Having a personal history with a subject only complicates this – but not always, nor necessarily in bad ways. I don’t completely understand my relationship to Vietnam as a writer. This collection is a testament to the fact that I’m becoming more and more okay with that.’ (Nam Le, interview with Knopf Publishers)

The story ‘Love and Honour and Pity and Pride and Compassion and Sacrifice’ examines this question of identity through the narrator’s relationship with his father and with Le’s own Vietnamese heritage. What must the son of refugees, a writer struggling to find his own way in the world, understand – not as an ethnically identified writer, but a universalist? ‘This story says as much about familial dreams and burdens as it does about the wages of history,’ notes critic Michiko Kakutani (2008). The struggle between the son attempting to understand and respect his father’s experience is a ‘struggle over authentic experience’ as represented by the father versus the imagined or recreated world as represented by the son/narrator (Goellnicht 2012). Resist as he may, his father’s story draws the narrator back to his roots.

The story’s title also speaks of Nam Le’s need to confront and maintain his compassion as a writer and can be read in the context of William Faulkner’s speech when he accepted the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969. Faulkner believed writers had a duty to capture humanity’s soul, with ‘a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance’. He also said:

‘It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.’ (Faulkner 1969)

The story also speaks of the complex and often conflicting generational experience of emigration. The literature of emigration has been called a literature of latency — it is held back or caught in some way which delays or defers its development. In a state of bereavement and impotency, the writer attempts to reconcile with the old, the new, the lost, and the discovered world. The new country — for which parents uprooted, leaving behind families and friends — doesn’t belong to the child born in the new country either. Andrew Lam sees the writing of Vietnamese refugees as private and circular. ‘History binds us all at the core, it is the ball and chain around a prisoner’s bleeding ankle. In it, the only moral direction to be had is the one that demands complete loyalty to the past — not to own it . . . but to let oneself be ruled by it, and to do so one has to accept forever the status of a stranger in a strange land’ (Lam page 34).

While Nam Le was less than one year old when he travelled to Australia by boat, the experience of his parent’s traumatic passage here and many more of these concerns can be seen in The Boat, in the opening and closing stories certainly, but also through the confused and dislocated characters in the other five stories. Le’s characters have been called ‘people in transit, people who, for one reason or another, have come unmoored and find themselves among other unmoored people, all of them trying to find their way to safety and stability’ (Wilson 2008). The reference to ‘unmoored’ people offers a link towards the book’s title and its eponymous final story — the author could be suggesting through each different tale that we are all adrift in some way. Or so we may think until we reach the collection’s final, harrowing insight into the most literal nature of displacement and exile. Le also takes the reader on a generational journey, from the acute gaze and confusion of the young man in the opening story to a hungry little girl in Japan, confused teenagers, love-lost women, old, ill men and the courageous refugees of the last story.

In a short story collection such as this, each story is carefully located in its own context, and the stories’ role in the unfolding continuum of the text offers insights into the author’s intent. The collection’s second story, ‘Cartagena’ follows the friendship between two young men caught up in an impoverished and darkly criminal underworld, and examines the ways in which trust and loyalty are tested in the struggle to survive. Just as so many of James Joyce’s characters imagine a better life away from Dublin, so too do the characters in this story imagine a simpler, happier life in Cartagena. Whether they will ever get there is debatable, which makes their desire for escape so much more potent. Other stories play on this desire for escape as well, whether it is a real release or a metaphorical one.

A contemporary reader of ‘Hiroshima’ is privileged with the knowledge of the bomb and its terrible aftermath and therefore reads the story cautiously and with concern for what is about to happen. Not so the story’s hungry young narrator with her youthful obsession with food and her separation from her family. This is what war means to her and she remains hopeful and optimistic all the way up to the nuclear flash of the story’s final moments. In ‘Tehran Calling’, Sarah, an American woman fleeing something at home to visit a friend in Iran, sees first-hand the ways in which people survive in post September 11th Tehran against an increasingly fundamentalist regime. Nam Le presents the reader with lyrical descriptions of the black-clad women who move about the city, their ‘chadors loose and flaring behind their bodies, shreds of shadow. Wind blowing against their faces, shaking the veils smooth as sheets on clotheslines’ (Le page 263). These are not descriptions of difference or hate, rather, we see people as buffeted by the wind as by the winds of fortune or fate, their humanness sympathetically portrayed through an image of flapping clothes familiar to all of us.

Henry Luff, the father in ‘Meeting Elise’, has left his reunion with his daughter too late. His health compromised and his daughter too alienated to comprehend his regret, he moves relentlessly towards his death — a man whose life has been spent recklessly, much as a spendthrift might splurge on things until all his money has gone. He looks back towards his lost youth surrounded by young people such as his lost younger lover, or the waiter in the restaurant, his daughter’s protective boyfriend and his daughter herself who ‘has wrung all of [my] weaknesses out of her strong, straight body’ (Le page 104). Self-awareness and regret come too late — the world belongs to the young.

This could not be said of Jamie in ‘Halflead Bay’ — a confused teenager learning the ways of the world through a series of painful lessons about love, mortality, place and friendship. Jamie is on the cusp of adulthood and ‘Halflead Bay’ carefully exposes the minefield inherent in the movement between both states — the child and the adult. This story makes much of its Australian setting, its descriptions capturing images inherent in Australian rites of passage. Take for example the school yard, toilet block and playing fields common to Australian schools, and gatherings of schoolgirls ‘opening apart, unfurling like some tartan-patterned flower’ (Le page 172).

The story ‘Halflead Bay’ examines the need for place and place’s role in shaping who we are, strongly conveying this yearning in its descriptions of sea and sand dunes, of fish and birds, scents and sounds, and the way people move through it all, shaped by it and becoming part of it. Like the young men in ‘Cartegena’, Alison and Jamie need to escape, but their desire is as much about escaping themselves and other people’s constraining needs. They want to redefine themselves and the story shows us their fledgling attempts to do so. What is Nam Le saying to us through these stories about love and family, betrayal and hope? That we are so alike despite our differences? And yet, in the first and the last stories — those two potent examinations of the Vietnam War and its aftermath — he draws our attention back to just how starkly different some people’s experiences are.

Critics have noted that at no point is The Boat actually called a short story collection and have asked whether, in fact, the stories should be approached as individual pieces or as a wider and more far reaching narrative, more like a novella or a novel (Wilson 2008). This question is often posed to collections such as The Boat. How might a reader read each story individually, remaining unaffected by the stories on each side of it? How, for example, should the reader approach the opening and closing stories and what insights do they provide about each of the other stories? Should we ask this question at all and just take each story as a narrative entity in its own right? What do the characters in each story have in common or should we read their difference as just that — emphatic and singular examples of how humanity experiences life differently — or do we see in each story’s characters the common human experiences of love and loss, betrayal, loyalty and hope? What does Henry in ‘Meeting Elise’ share with Juan in ‘Cartagena’ or school children in Hiroshima and their counterparts in Australia? How do all these characters fit within the framing narratives of filial concern and massacre, flight and refuge in the first and final stories? In writing so diversely Le seems to be asking us to consider our connections and disconnections at the same time.

The Boat is rightfully seen as an exemplar of the short story form. Le wrote much of it while participating in the Iowa Writer’s Workshop in the United States, and each story bears the hallmarks of a carefully thought out, well-crafted and edited reflection on the short story form and the artistic skill necessary in the successful realisation of it. As well as its fine writing, its carefully drawn characters, the use of place as both a locating medium and a metaphor for existential conflict, it also raises questions about the commonalities and the distinctiveness of lived experience. Can I assert that I know how it must feel to live in Tehran or Hiroshima, in Colombia, or to have lived through the Vietnam War? No, I can’t. I can only enter the zone of experience thorough narratives such as these and trust — a word so potently sub-textual in this collection — that I can imagine, reflect, and attempt to understand. And perhaps that should just be enough.

Referenced works

William Faulkner — Banquet Speech. Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2013. Web. 1 Jul 2013.

Goellnicht, D. “‘Ethnic Literature’s Hot’: Asian American Literature, Refugee Cosmopolitanism, and Nam Le’s The Boat.“ Journal of Asian American Studies 15.2 (2012): 197–224.

Kakutani, M. International Herald Tribune 13 May 2008.

Lam, A. Perfume Dreams. Heyday Books: Berkeley, California, 2005.

Lee, C. “Asian American Literature and the Resistances of Theory,” Modern Fiction Studies56.1 (Spring 2010): 19–39.

Le, N. The Boat. Penguin: Camberwell, Victoria, 2008.

Penner, J. The Washington Post 16 Jul 2008.

Pincus, R. The San Diego Union-Tribune 18 May 2008.

Wilson, A. Los Angeles Times 6 Jul 2008.

All book reviews accessed through Nam Le’s website, which also provides extensive materials for students and teachers of The Boat.

© Copyright Catherine Cole 2013

(7 votes, average: 4.43 out of 5)

(7 votes, average: 4.43 out of 5)