Essay by Kim Mahood

The death

On the morning of November 19th, 2004, an Aboriginal man named Cameron Doomadgee died in a prison cell on Palm Island, off the coast of North Queensland. He had been arrested less than an hour earlier by Senior Sergeant Chris Hurley, for being drunk and causing a public nuisance. A post mortem revealed that he died as a result of a burst portal vein and a split liver; injuries of the sort that normally occur only in high impact accidents. Throughout the inquest and trial that followed, Chris Hurley maintained that he had not assaulted Cameron Doomadgee. Through a controversial series of legal processes he was found to have a case to answer and charged with assault and manslaughter — the first time in Australia that a police officer had been charged over an Aboriginal death in custody. He stood trial and was acquitted by a Townsville jury in June of 2007.

This event and its consequences brought into harsh focus the fault lines that run through Australian society — between the police and Aboriginal people, between the north and the south, between those who believe that all human lives have equal value and those who do not.

The island

Palm Island is the largest of a group of islands sixty kilometres north of Townsville. In 1918 it was deemed suitable for use as a penitentiary, and until the late 1960s it was the site of a mission and penal settlement. Aboriginal people from many different language and kinship groups were sent to the island for various crimes and misdemeanours, sometimes simply for being of mixed European and Aboriginal descent (this being the era of forced removal of children from parents).

The island’s history provides us with a dark mirror of the values that selected Australia for the same purpose more than a century earlier, a place in which to consign society’s discards, ruled by a punitive and paternalistic authority. Statistics compiled between 1977 and 1984 indicate that the rates of homicide and violent crime on Palm Island were considerably higher than those of other remote Aboriginal communities, which were already considerably higher than the broad population (Wilson page 49). For many years Palm Island has been synonymous with the most extreme Indigenous dysfunction, alcoholism and violence.

The police

Between 1987 and 1989 the Queensland Police Department came under the scrutiny of the Fitzgerald Enquiry into police corruption. The findings of that enquiry identified an embedded culture of high level and systemic corruption, and resulted in the ousting of the Bjelke-Petersen Government and the jailing of the Police Commissioner Terry Lewis. Although many of the Fitzgerald recommendations were implemented, the police culture of loyalty and solidarity among its members remained entrenched. Indeed studies suggest that the nature of policing requires and reinforces these qualities, and that the unwritten rules of police culture promote conformity and solidarity (Lawson 2011).

The author

About two months after the Palm Island incident Chloe Hooper chanced to meet the lawyer Andrew Boe. Boe was representing the Palm Island Aboriginal Council pro bono in the investigation into Cameron Doomadgee’s death, and wanted somebody to write about the case. Hooper was in her early thirties, and had spent most of the preceding decade overseas. She knew almost nothing about Indigenous Australian culture, had never met an Aboriginal person, and had published a single work of fiction, A Child’s Book of True Crime. This proved to be an ideal combination. Having no pre-conceptions, Hooper brought a non-judgmental but forensic eye for detail and a novelist’s sense of structure and dramatic tension to the case.

The genre

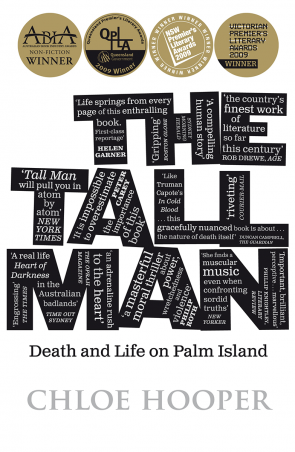

In the best tradition of a form of writing that has come to be called creative non-fiction, Hooper uses the techniques more commonly used in fiction to create a suspenseful and powerful story. Since the form became popular, most notably with the publication of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood in 1966, this kind of writing has been criticised for allowing literary structure and technique to distort the truth. In the interests of a compelling narrative, devices such as metaphor, coincidence, historic precedence and suspense may imply significance where none exists. The irony may be that the greater the literary merit the greater the risk of misrepresenting actual events.

Whether The Tall Man warrants this sort of criticism is a question that could be introduced into discussion based on a close reading of the text, along with a discussion on the merits of enticing readers to pay attention to issues they might otherwise avoid.

The story is structured around a chronological sequence of dramatic events — The Death, The Riot, The Inquest, The Funeral, The Rally, The Trial, The Verdict — interspersed with discursive chapters — The Island, The Family, Belief, Burketown, Amazing Grace — through which Hooper teases out the back story of her protagonists, and provides the context in which the events occur.

She builds character and narrative through precise observation, detail and dialogue, revealing the complexities and contradictions of individuals, the cultures they inhabit and the events that overtake them, so that the reader becomes both witness and participant in the unfolding story. She is mistress of the telling detail. For example she observes that when the Aboriginal mayor of Palm Island calls in to the hospital, the white nurses don’t know who she is; an indication of how segregated the two groups are from each other. And she notes that only the lawyers and journalists use the traditional term ‘Mulrunji’ to refer to the dead man, while everyone else continues to call him Cameron. This speaks volumes about the mismatch between the desire to respect cultural sensitivities and where those sensitivities actually reside.

Always present but never intrusive, Hooper is a guide one is predisposed to trust, a moral compass to lead us through the story. We are witness to her feeling ‘incandescently white’ on her first visit to Palm Island, we experience the events, the people and the places through her ever-observant, questioning, compassionate scrutiny, and share her dilemmas and discomforts as she attempts to assemble the puzzle of the Tall Man.

* * *

In the northeast tropics of Queensland the Tall Man is a malevolent being who comes out at night from the cracks in the rocks or the shadows of the rainforest and does bad things. A creature of nightmare, he is to be avoided at all costs, especially if you are Aboriginal. That November morning on Palm Island Cameron Doomadgee encountered him in broad daylight, in the shape of the two metre tall Senior Sergeant Chris Hurley.

The Tall Man is a tale of parallel tragedies. At the centre of it are two men, both thirty-six years old, representing two tribal cultures historically enmeshed and at odds with each other. Indeed the book opens with a description of a painting on the wall of a Cape York rock art gallery, of two policemen lying prone with guns trained on two Aboriginal men, also prone, also with guns. Painted in colonial times, one of the policemen is two metres long, his half- naked lower body cross-hatched to resemble the skin of a crocodile. A painted snake four metres long bites his foot; a piece of sorcery designed to activate a curse on this particular Tall Man. Did it work? We will never know, but probably not. Even with the enlistment of sorcery it was always an unequal contest.

The active power resides with the Police. It is the enforcement arm of the Law, disciplined, educated, well-fed, salaried. It shares a code of solidarity, it is endorsed and paid for by the government, it represents the bulwark of law and order against crime and disorder. Its adversary is the lost tribe, castaways on an island microcosm of concentrated dysfunction and collective damage. Deracinated, detached from the old Law that still holds some sway on the mainland, their power is the power of endurance and of survival.

To begin with the tragedy seems restricted to the Aboriginal community, framed by the legacy of historic disenfranchisement. A man dies in custody. His family are shattered. The verdict of accidental death triggers a riot in which the police station is burned, for which people are charged and imprisoned. Two young men commit suicide as a direct result of Doomadgee’s death.

But as the story progresses the moral ground tilts. Whatever happened in the corridor of the Palm Island police station on November 19th 2004, there is enough evidence for the Deputy Coroner to find Chris Hurley responsible for Cameron Doomadgee’s death. Hurley’s insistence that he did not assault Doomadgee shifts the moral centre of the story to an examination of his character, and the way in which his colleagues rally behind him even though, in the words of one of them ‘”We acknowledge that he could have, there’s no two ways about it. I haven’t heard one person say, ‘Look, Chris is innocent,’ no one’s saying that”‘ (Hooper page198). The Queensland police force supports Hurley not because they believe he is innocent but because they know it could have been any one of them. From a man who had faced down his own racism, and appeared to be making a genuine difference at the coalface of Aboriginal and police interaction, he became the vehicle of divisiveness.

No-one suggests that Hurley is a racist, and the closing of police ranks to protect him is not racist but tribal. But the circuitry for racism is ready-wired, and it is along these pathways that the message travels, fuelled on both sides by a sense of injustice. The Aboriginal population believes that Cameron Doomadgee’s death is accorded less value because he is Aboriginal. The police believe that Chris Hurley has been made a scapegoat out of political correctness. Sides are taken. The Urban South excoriates the Deep North. In Townsville, where the trial is held, the line of demarcation is drawn between white and black.

Chris Hurley is the absence at the heart of the story. Because he refused to be interviewed by Hooper, she visited the towns and communities where he had worked, talking to people who knew him, building a picture of his family background, his Catholic education and upbringing, and his relation to the people with whom he worked, both Aboriginal and white. It is through the voices of Aboriginal activist Murandoo Yanner and his brothers that the contradictions that are Chris Hurley come through most clearly. Murandoo Yanner is himself a contradiction, a charismatic powerbroker with his own political agendas. The Yanners describe a man who was genuinely engaged with Aboriginal people, who worked enthusiastically with the kids, who made the sort of pragmatic arrangements that short-circuited the need for criminal charges over minor offences. It’s clear that they hold him in high regard, and that they consider him guilty of the assault. It’s also clear that it is not the assault they condemn but the refusal to admit that it took place. In that world everyone understands how easily the undertow of violence comes to the surface.

Place is as powerful a protagonist in this story as any of the human characters. Heat and humidity seep through the pages, claustrophobic and stupefying. The landscape is omnipresent, whether in the crocodile-infested estuaries or the heat-stunned towns or the landforms created by the activities and natural functions of ancestral beings. The north of Australia is a different country. People are proud of their ability to live there. Along with the toughness goes a certain simplification that can have its own appeal; ‘the proximity to sex and death and beauty and horror; to songlines that are badly frayed but still give off some charge; to what is ancient, our deepest fear that good and evil spirits make sport with us’ (Hooper page 119).

Hooper is scrupulous in her portrayal of the visceral, dangerous environment in which Chris Hurley was vested with carrying out society’s dirty work. At the trial she watches him in the dock and frames the questions she would like to ask him.

Do you ever dream you are falling?

Do you ever dream of Cameron Doomadgee?

What do you think of the places you once chose to live, where good and bad are blurred, and where you thought you were good?

Do you still think you were? (page 237)

When she realises he is looking at her she can’t hold his stare. ‘He was a man trying to save his life and he seemed to be saying, How dare you judge me?’ (page 238).

Hooper takes us on a compelling quest into one of our deepest cultural fault lines, a place that most Australians would never enter by choice. One of the strengths of this book is her ability to make the Palm Island people real, in their tough, provisional, often violent lives, and to make us care about them without overlooking the reality of the way they live. She gives a voice to people who are rarely heard, makes us care about people who are usually invisible, and she makes us understand that we are all implicated in Chris Hurley’s actions and in Cameron Doomadgee’s death. Although she does not conceal where her sympathies lie, neither does she condemn Hurley. Instead she suggests that the trajectory of two lives towards the fatal encounter that left one of them dead and the other terminally compromised was inscribed in their cultural DNA.

It is in this fatalistic representation of events that The Tall Man has attracted criticism for its suggestion of historic and cultural inevitability. Hooper’s literary references, (for example Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, with Hurley cast as Kurtz, and Palm Island as the dark heart of Queensland), and her linking of Hurley with archetypal and mythic characters, leave little possibility for change or agency. It is here, once again, that the conflict between literature and journalism arises, since it is in the use of these mythic tropes that much of the book’s imaginative power resides. It is a cross-cultural parable and a morality play, conflating the malevolent demon of the indigenous north with the fatally flawed protagonist of Shakespearian tragedy. Its language is distilled and without ornamentation, its structure unobtrusive, its people complex, flawed and sympathetic. It goes to the heart of one of our most intransigent cultural dilemmas and reveals the fears, resentments and prejudices that run beneath the surface, and the institutions that both reinforce and interrogate them.

The Tall Man is testimony that although the Palm Islanders lost the legal fight they won the moral battle. Like all great works of literature it tells a story that is both local and universal. ‘I am not my brother’s keeper,’ Cain tells God after he has killed his brother Abel. A parable of the conflict between the settler and the nomad, the biblical fratricide of Genesis is a blueprint for the ancient distrust between different kinds of order. What The Tall Man makes us understand is that if we fail to be our brother’s keeper, we fail ourselves.

Postscript

In 2010 the Queensland police attempted to have the deputy coroner’s findings expunged from the records, allowing the acquittal to stand as the evidence of Senior Sergeant Hurley’s innocence. In agreeing that the findings were flawed, the magistrate found enough grounds to warrant a second inquest, in which it was found that the police colluded to protect Hurley. This meant that the initial evidence was contaminated, and while it was not possible to prove Hurley guilty through the courts, it showed that the legal system could be flexible enough to bring the contradictions and inconsistencies into the light.

Doomadgee’s family continued to pursue a civil claim and were awarded compensation in 2011 under the Victims of Crime Compensation Scheme, effectively acknowledging that a crime had been committed.

Referenced works

Hooper, C. The Tall Man: Death and life on Palm Island. Penguin: Melbourne, Victoria, 2008.

Lawson, C. ‘Police Culture: Changing the Unacceptable.’ SCAN Journal of Media Arts and Culture8.1 (2011).

Wilson, P. ‘Black Death White Hands Revisited: The Case of Palm Island.’ Australian & NewZealand Journal of Criminology 18 (1985): 49–57.

Suggested reading:

Creative non-fiction

Helen Garner Joe Cinque’s Consolation

Truman Capote In Cold Blood

Janet Malcolm The Silent Woman

Indigenous references

Henry Reynolds Aborigines and settlers: the Australian experience, 1788–1939

W.E.H. Stanner The Dreaming & Other Essays

Other material

© Copyright Kim Mahood 2013

(5 votes, average: 3.40 out of 5)

(5 votes, average: 3.40 out of 5)