Introductory activities

Mixed- or multi-media collage

Café Scheherazade requires students to have some background knowledge of the situation of Jews in Poland before and during World War Two.

Students should read and view the websites listed below to begin to understand the context of the characters in the novel.

They could then make selections of words and images to develop a collage which conveys an aspect of the life that is described by the characters or, if students have not yet read the text, they predict will be a feature of their lives based on their reading and viewing of the sites.

In their collage they:

- could use print or digital materials,

- construct images in any form or in a sequence,

- compose a text that resonates emotively,

- use quotations or captions,

- give their text a powerful title.

Collages could be published digitally, hung on the wall or form a part of a classroom presentation.

Resources

To gain an idea of the period, students should read at least one of these texts on Jews in:

- Vilna

- the Vilna Ghetto

- Warsaw

The following websites include contemporary film footage of places known to and events experienced by the characters who frequent the Café Scheherazade.

- The film footage that is frequently seen on the web is taken in 1939 in Warsaw by a returning émigré from Eastern Europe. Students need to note that this is taken in the Jewish quarter, a poor area, in Warsaw where the orthodox lived. The characters in the novel claim to be secular and so would have lived and dressed in the European style. For example, Yossel speaks nostalgically of Krochmalna Street which is a broad and busy avenue with substantial shops and buildings.

- Photographs that have now become iconic were taken by Roman Vishniac from 1935-8. These were commissioned by a Jewish relief agency to raise money for and awareness of Jews suffering privation as a result of anti-semitic laws in Germany and Poland. Again, while these are very evocative and, in the knowledge of what followed, are most poignant, their focus is also on the orthodox and the poor.

- For students who have no or little knowledge of the Holocaust, the series of short films“What is the Holocaust” from the Yad Vashem (Israel’s Holocaust museum) website provides clear, and dispassionate, summaries of the rise of Nazism, Nazi attitudes to the Jews, their policies and how they implemented them.

- This video was made as a tribute to Jewish Partisans and has images of actual fighters, art works and is backed by the ‘Partisan song’ in Yiddish and Hebrew.

- The virtual tour of the recently opened Museum of the History of Polish Jews gives a more general view of Polish Jewish society. Starting at the section The Street 1918 – 1939 (7.35 minutes in) will allow students to focus on the appropriate period.

- This film was made to explain the founding of Zegota, an underground agency to aid Jews under the German occupation of Poland.

Another source of information and images is the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Note: Care needs to be taken in ensuring a reliable source. Websites as search engines cannot discriminate between bona fide information and information promoted by Holocaust denialists. Often one only recognises the anti-Semitic strain some way into the article or the video.

Framing the stories

Draw students’ attention to the dedication at the beginning of the book:

To Melbourne’s first storytellers:

the Wurudjeri and Bunurong people.

And to all those who are still in search of a haven,

a place they can call home.

and to the epigraph about Scheherazade.

Then direct them to pages 220 and 221 to the paragraph: Storytelling is an ancient art . . . the first moments of love and hate.

And to the last words of the text: And, seeing that the dawn had broken, Scheherazade fell silent, as at last she was at liberty to do.

Ask them to consider:

- what expectations are produced by these cultural references?

- to what extent these references resonate as they read through the text?

Like One Thousand and One Nights and other classic tales such as The Ramayana, The Odyssey, The Canterbury Tales and The Decameron, Café Scheherazade uses a framing device for its stories. It begins with Martin, a journalist assigned to write an article for his newspaper about this Melbourne icon, who begins to interview regulars at the café only to find that their stories are too rich to be confined to this short form and requires a book. The stories are connected by their fictional context of the café conversations and by their historical context of Polish Holocaust survivors who were finally able to make their home in Melbourne and frequent the same café.

Framing devices are not unusual and can include:

- ‘bookends’ with the central story embedded in a new, usually everday context of some kind;

- flashbacks where the story begins at the end, flashes back to the beginning and then through the story to explain or recontextualise the first scene. These are sometimes intended to explode readers’ or viewers’ first impressions of characters or situations.

- nested stories where characters in stories tell stories of their own.

The image below is of the real Café Scheherezade which frames the individual stories that are told.

http://www.yourrestaurants.com.au/guide/scheherezade/2304

From their own reading and viewing students could:

- brainstorm other framed narratives from the three types above;

- suggest other kinds of story framing that they have found in their reading and their viewing;

- choose one frame story to consider more deeply; and,

- write a paragraph describing the frame and how it relates to and enhances the core narrative.

Outline of key elements of the text

One way of covering the breadth of the text and understanding the range and diversity of characters’ experiences is to divide the class into groups, each taking one storyteller as a focus. Each then becomes the expert group for the experiences and ideas of that character.

- Avram (Avram’s section could possibly be divided into 2 groups, one dealing with his own story and the other of his parents.)

- Masha

- Laizer

- Yossel

- Zalman

The groups could then chart the experiences of their character through such details as:

- Noting the where, what and why.

- Recording the year of each incident, and

- Mapping the enforced journey, and

- Selecting 3 key quotations that convey the essence of the storyteller’s experience.

Their findings are presented to the class as speech, writing and visual representation to communicate the experiences as vividly and clearly as possible.

In groups, students then devise a graphic representation comparing each character’s experience across the years of the war to give a sense of the range of experiences and the vastness of territory covered. These may be blended into a timeline so that each character’s experiences may be compared to the others’.

Synthesising task

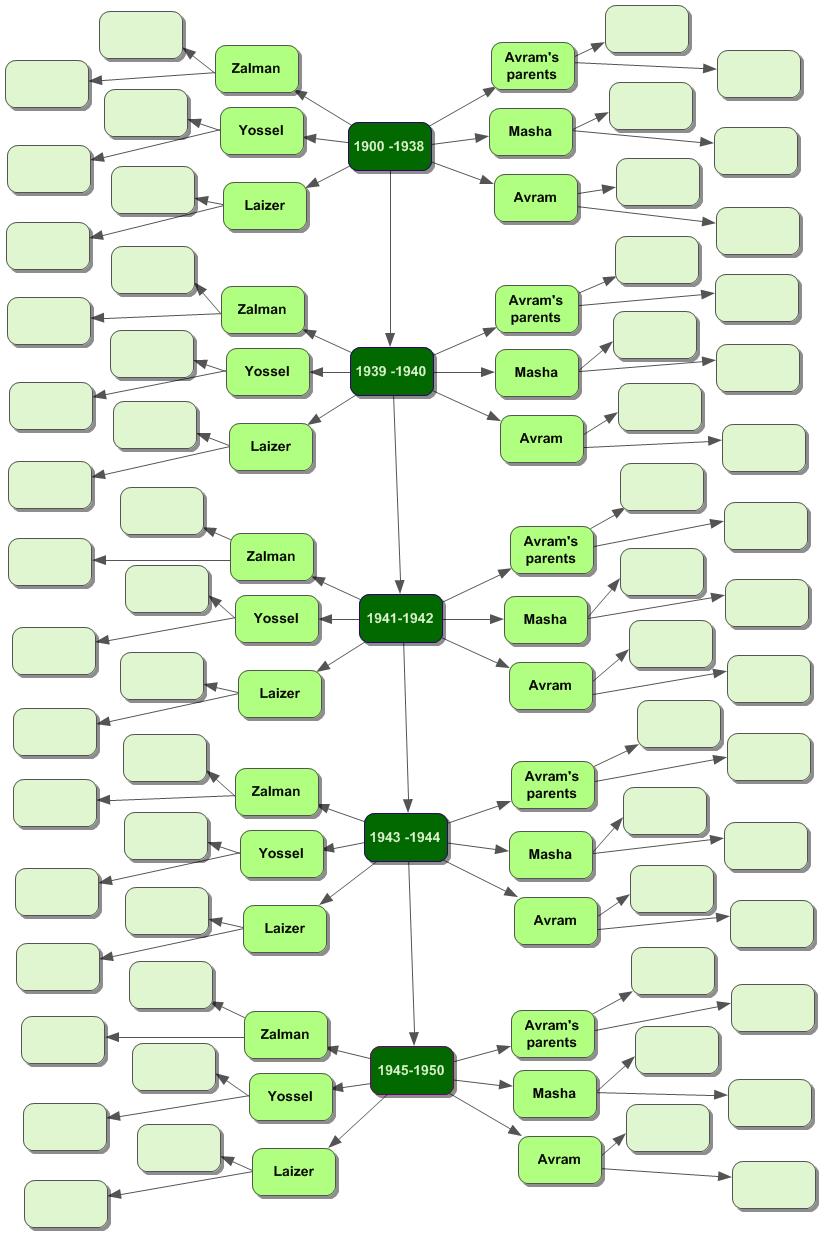

Students use their research to build a hypertext based on the experiences of the characters in the novel. One way of organising this is through a timeline, as illustrated below, with:

- the main navigation being the years in the stories (dark green),

- linking from these each character’s experiences in that period (mid green), which in turn

- link out to items of historical or geographical interest that emerge from the story.

Some stories will be able to link to the same or similar information. Students are encouraged to enrich their pages by images, film footage, readings of the text, dramatisation of scenes or any other technical capacities of the web.

The writer’s craft

Characterisation

The individual stories of this novel emphasise events, the extraordinary experiences of ordinary people, battered by history. The characters are not real but realistic, based on ‘composite characters, whose fictional journeys are based upon tales . . . of many survivors’ (Author’s note, p. 222). The characterisation is the imitation of real people, a construct of traits suggested through what they say, how they say it and what they do. The combination of traits is coherent and presents engaging personalities with whom we empathise strongly. Given that we cannot see their private thoughts beyond what they tell the narrator, students can discuss whether these characters are only partially realised. In this sense they could be seen as archetypes, representative of Holocaust survivors, refugees or displaced persons who have found sanctuary in a new home and have flourished.

Student activity

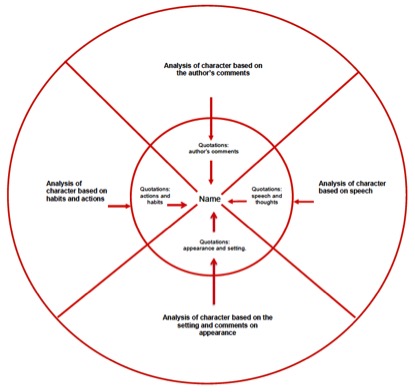

To address these ideas students could analyse their allocated character in a conventional character wheel such as the one below.

On the basis of their analysis, half of the students could write a character study of their storyteller and the other half could develop a profile of a survivor. They could then compare these to see how closely the character study and the profile resemble each other.

The class could then discuss to what extent the characters are fully realised, are survivor archetypes or both.

Setting

There are several images of the Café Scheherezade on the internet (note that the spelling of the café in the novel is consistent with the accepted spelling in English of the heroine of the One Thousand and One Nights, Scheherazade, however the actual café was spelt Scheherezade.) which can be found on the St Kilda Historical Society web site. However the most evocative description of the setting is on pages 20–22 of the novel. (Like a magnet Scheherazade draws them . . . journeys in search of refuge, a shelter from a curse.) The café is portrayed not so much as a place but a society, alive with stories and voices clamouring to be heard.

The settings of the stories vary and spread across Europe and the Far East and as the stories, and the war, progress they become increasingly harsh, each one gruesome in its own way.

The framing device of the local café, a familiar and welcoming setting to both characters and readers, brings the terrifying world of the stories into an environment that makes them reachable but safe. It tells us that, at least for the storyteller, there is a positive, if not a happy ending. The café society tells us of horrors and death while reaffirming growth and life. In doing so it redirects the reader’s view of the worlds created in the stories and shifts the themes of the novel from inhumanity and brutal destruction to survival and regeneration.

Narrative technique

Speaking about the unspeakable

It is critical that survivors of atrocities be given a voice, for their own healing and for ours. Yet in the early years after the war, most holocaust survivors had to struggle both to tell their stories and to be heard.

It is difficult to believe today but aside from Primo Levi’s If this is a Man (published in Italian in 1947 but in English only in 1959) and Elie Wiesel’s Night in 1960, there was little spoken about the horrors of the Holocaust. The post war period was marked by survivor silence partly because of the rawness of the experience but mainly because of the limitations of language to evoke to experience. Jews who had stumbled out, barely alive, from the ashes of Europe in 1945, discovered that they were witnesses to events that they did not have words to express and the world would rather forget.

Ruth Wajnryb, a linguist and daughter of Holocaust survivors of the Vilna ghetto and Auschwitz, explores this in her book The Silence: how tragedy shapes talk.

When I heard people ask my father questions about the war – ‘Did you lose your family in the war?’ ‘Did your parents die in the camps?‘ I knew without knowing that these verbs ‘lose’ and ‘die’ were inadequate for the task. I sensed how the differential between their meaning and the reality threatened to engulf and capsize the conversation . . . Many times I saw him hesitate momentarily when asked such a question; he would seem to be quelling something within; and then he would nod silently.

It’s a familiar refrain among survivors who say, like Mark Baker’s parents in The Fiftieth Gate, ‘You can’t understand if you were not there’. This makes the decision to use a sympathetic narrator, one steeped in Yiddish and Jewish traditions (as indeed is the author) an understandable context in which these stories can be candidly told.

Narrative voice

The narrator, Martin, is a character in the novel who retells the stories of Holocaust survivors. They recount their experiences to him as does Avram in ‘lilting Yiddish. Each word . . . carefully wrought. Each sentence . . . [having] its melody, each paragraph its song.’ While these are their stories and the stories are seen through their eyes, we do not often hear their voices directly. The narration is generally in the third person with occasional interjections or extracts of direct speech, further animating the stories and commentary, for these survivors are vivid personalities. This narrative approach is an added touch of realism to remind us that when the survivors slip ‘into English there is a continuity in syntax’ from one of their other languages which may not translate well into the written form.

The result of this authorial decision is firm narratorial control of the patterns and sounds of storytelling. In doing so he guides how the stories should be interpreted and, while we have multiple stories, we have one attitude towards them, a caring and sympathetic one.

Student activity

In understanding the role of the narrator in this texts students could discuss in pairs:

- To what extent the narrator is inside and outside the story/ies.

- To what extent and how he reflects on the storytelling process.

- How emotionally involved he is in the story – his own and the embedded stories.

They may find these extracts helpful:

What had begun as a simple newspaper story has exploded beyond my grasp. I listen. And I record. Driven by the knowledge that the old men are moving on, nearing the ends of their tumultuous lives; driven by a sense that is would be a tragic betrayal if their stories disappeared without trace.

Martin p. 59

I have sensed the vastness. I am plotting lines that form ancestral maps, that unify fractured journeys across continents and oceans; lines that convey ancient melodies and longing, and twist and curve and break off into unexpected detours, to converge upon a café called Scheherazade.

Martin p. 65

Every few weeks I hear of another death . . . A generation is moving on. And with each passing life I feel it more keenly: there are tales aching to be told, craving to be heard, before they too disappear into the grave.

So I return to the café, to the remaining storytellers, to listen and record. To inscribe and pass on. And in so doing, to add to the mythology of an ancient land.

Martin pp. 112-113

Having discussed these questions and explored the text to find supporting evidence for their ideas, they could write an extended paragraph on the role of the narrator in Café Scheherazade.

Narrative Style

The narrator seamlessly slips from his own thoughts into the experiences recounted by the storytellers. His lyrical style is easily heightened to a poetic intensity or pared down to bare statement of facts. He achieves this largely through rhetorical, rhythmic and sound devices rather than surprising diction or complex imagery – a style that evokes the resonances of a sensitive and measured spoken voice.

Following a teacher modelled analysis of a personal favourite passage, students could do a stylistic analysis of the following extracts annotating them for rhetorical devices such as:

- Repetition

- Cumulation

- Balance

On that night, under an impassive moon, Laizer discovered parallel universes, hovering side by side, one of beauty, one of ugliness, one permeated by darkness, the other suffused with light. On that night Laizer regained his childhood sense of naivety and awe; and he realised that by learning to manoeuvre between these alternate universes he could generate the charge of energy necessary for him to pull through. On that night, Laizer became a survivor.

Laizer’s story p. 64

On 1 September 1943, the ghetto is sealed off. In the following weeks thousands are herded towards the Vilna station. Those still capable of work are transported to labour camps; the men to Estonia, the women to Latvia. The old, the sick, the lame, the remaining women and children, all those deemed not fit for slave labour, are trucked out the be shot in Ponary, or entrained to the gas chambers of Majdanek. The final liquidation of Vilna ghetto has begun.

Avram’s story p. 165

There are of course other voices in the novel, the voices of the storytellers. These are usually filtered through the voice of the narrator. However, there are a few times when they are supposedly heard directly and these sections are signalled by inverted commas. Here we can get a sense of the characters coming through in what they say and through their tone.

This is a tale of maps, both old and new. Maps with shifting borders. Obsolete before the ink could dry. Maps that created bands of nomads, stateless refugees. Maps criss-crossed by trains shunting their cargoes of uprooted wanderers thousands of kilometres east, on a nine-week journey, over glacial plains and snow-capped ranges through white nights and broken days, an interminable journey that came to an abrupt halt at a remote station.

Masha’s story p. 50

Student activity

Returning to their character profiles, students could do a close study of the following extracts and consider:

- to what extent the language indicates the character traits they have identified; and,

- how the language of the character shapes our attitude to them.

In small groups, each focussing on one of the characters, students could then experiment with reading the extracts in what they imagine could be the voice of the speaker. They comment on each other’s reading and advise how to make it sound an expression of the character they outlined in their analysis.

A rehearsed reading of each monologue is presented to the class with a commentary on why this particular rendition was chosen.

Masha’s voice

Two weeks later we set out again, this time by train for Warsaw. Poland was under siege. I was afraid. And I was excited. I had been entrusted with a mission. Father told me to take charge. Mother remained silent because her Polish was heavily accented. She could easily be identified as a Jew. I was to do the talking. I loved the responsibility. I felt like an adult.

p.47

Laizer’s voice

It was a comedy. Our toilet was a drum, standing in the corner of the room. The room did stink of our own waster. We smelt like vagrants, unwashed tramps. We had a daily rations of bread and diluted soup. You could not call it soup. It tasted like swamp water. Every fortnight we received a matchbox full of sugar. This was our first great luxury. There was only one window, high up, and through it, from a certain prized position, you could see a patch of sky, a ray of sun, or dark clouds rushing by. Or, sometimes, even the moon. This was our second and final luxury.

pp. 60 – 61

Zalman’s voice

You could feel it…The city [Shanghai] was unhinged. There were even buildings rising from concrete rafts which, in turn, floated on mud flats. In the side streets, abandoned children covered in sores ran in packs. Beggars tugged at your sleeves. I saw the desperation in their eyes. Those who were making a living hurried by. They did not look. They did not wish to see. Those well-off snuggled back in their cars on their way to the cabarets and private clubs.

p.118

Yossel’s voice

Yet somehow for me, Shanghai was a beautiful life. That is how I remember it. What do you want me to say? That I am ashamed? That I should not have enjoyed myself when I had the chance? If not for Mao I would have stayed. Even at the worst of times I still loved it. During my six weeks, en route, in Kobe, I sold the diamonds I had smuggled from Vilna; and I arrived in Shanghai with cash in hand.

p. 142

Avram’s voice

In the swamps and forests we were kings. We lived by our instincts and wits. When the Luftwaffe planes circled overhead we would hide in the mud. They were too frightened to come by land. We could remain invisible in the swamps for hours on end. We ate grass and drank our own urine to ease out thirst. We learnt that everything can be turned to an advantage. When the planes dropped their bombs, they would get stuck in the mud. We would creep up, defuse them, take out the explosives and use them in our mines.

p. 174

Themes

In groups students note characters’ statements about such ideas as:

- Freedom

- Continuity/discontinuity

- Powerlessness and loss of control

- Loss

- Displacement

and note them, the storyteller and the page reference on post-it notes, which can be copied and distributed to the other groups.

Each group:

- discusses the various statements;

- categorises them into thematic clusters; and,

- develops a thematic statement using these clusters as supporting evidence.

Groups can compare their decisions.

Synthesising task

This activity may require some differentiation in ability as the poem on p. 87 is more difficult than that on p. 164 and the second task is more difficult than the first.

Divide the class in two and have half look closely at the poem on p. 87 and the other half at the poem on p. 164. Of these two groups, have half complete the first (easier) activity and the other half complete the second (more difficult) activity.

Task 1

Students work in pairs and describe:

- the possible speaker of their poem

- the addressee and

- the intended audience

as the raw material for answering the question:

- What is the relationship between the speaker and the reader of the text?

Task 2

Students identify and explain the paradoxes stated or implied in the poem as the basis for answering the question:

- How does the tension arising from the oppositions in the poem evoke its themes?

They may need some guidance here with questions such as:

- What grows / what dies? (p. 164)

- What is lost / what remains? (p.87)

They then share their results with the other students working on the poem and decide how they are going to present their findings to the half of the class working on the other poem.

After the presentations and class discussions arising from them students complete an essay:

To what extent can the two poems be said to summarise the concerns of the novel?

(ACEEN024) (ACEEN025)

The importance of stories

In its title, its structure and its content, this novel values and attests to the importance of telling one’s stories. Students can be invited to appreciate the significance of storytelling to our lives and the very nature of being human.

Student activity

Students can produce a range of texts using the novel.

Text 1

An argument for the importance of stories.

Students could read the quotations from Café Scheherazade below and the following web sites that argue for the importance of stories in different ways.

This is a tale of many cities: each one consumed by the momentum of history. Each one recalled at a table in a café called Scheherezade, in a seaside suburb that sprawls upon the very ends of the earth, within a city that contains the traces of many cities.

p. 7

They continue to tell their tales, as if to talk is to know they have survived.

p. 33

‘And what my philosopher friend, can anyone be sure of?’ asks Laizer.

‘Perhaps only stories’ says Zalman. ‘The rest is speculation.’

p. 65

‘Yet there were other times, as I trudged from one hour to the next, when I believed that one day I would prevail, that one day I would tell my unbelievable tales. I imagined that I would bring back a deeper truth about the taunting beauty of nature. I would bring back my experience of human indifference and expose the system that produced it. I imagined the astonished faces of the friends and family I had left behind, how they would hang on every detail, on each measured word. I did lie awake at night, beside my snoring workmates, and conjure the picture of my triumphant return. I saw myself walking the final steps to the door. I would tell my story, and my life would not have been wasted.’

Laizer p. 50

Text 2

An animated essay on why great storytellers matter more than ever in helping us make sense of an increasingly complex world.

Text 3

A blog on the importance of stories.

Text 4

An article on how narrative is a basic organising principle of memory.

In small groups students choose one of the texts (the class should cover all four texts)

- Summarise its argument.

- Analyse the way language is used to present the argument.

- Assess the effectiveness of the text for its audience, purpose and context.

Groups considering the same text come together to share their findings and synthesise them for a presentation to the class.

(ACEEN021) (ACEEN022)

History/story

The Shoah Foundation, an historical archive, founded by Steven Spielberg hosts many personal stories of survivors. They have been recorded as historical documents to further the remembrance of the Holocaust. Many of these testimonies take several hours, but below are two extracts that took place in Poland.

Students may be directed to view the first minutes of the interviews as the details of the witness are recorded before moving to the extract itself. This adds a layer of formality and authenticity to the recording.

- Helena Jonas Rosenzweig (41.40 – 50.00)

- Michael Zelon (1.07.30 – 1.19.33).

Another source is the interview of Jan Karski by Claude Lanzmann in the making of Shoah.Jan Karski was a spy for the Polish Free Government in exile, who was smuggled into the Warsaw Ghetto and Belzec concentration camp. His assignment was to report the atrocities there to the allied governments, in the hope of securing some way of preventing mounting death tolls.

Jan Karski: The Messenger (23.30 – end; 17 mins)

Full transcript

In all these interviews, the speakers try to maintain a detached tone to project a sense of objectivity, fully aware of the importance of their contribution to the historical record. These are simple descriptions of fact. However, there are times when they are overcome by the power of memory and narration.

Class Activity

History is made up of stories, not all of them heroic. History should acknowledge heroism, and creating a website devoted to the work of those who did not stand by and watch injustice is one way to do so.

A simple, free and popular platform is Weebly. Using their area of interest as a guide, students can be divided into groups focusing on aspects of the project such as:

- Content development of individual stories.

- Website structure, navigation and development of style and of the home page.

- Technical production including filming of monologues and uploading of content.

Students should start by researching Chiune Sugihara, Raoul Wallenberg, Oscar Schindler, Irena Sendler, Ho Feng-Shan and looking at some of the stories of the righteous amongst nations.

They might also find it helpful to read about how to develop monologues. This one from ATYP focuses on dramatic monologues.

Using the same testimonial style of the survivors, students draft a monologue in which one of the righteous amongst the nations gives an account of:

- what they saw,

- what they understood,

- what they did to save the lives of victims,

- the dangers involved, and

- how they felt at the time.

The intention would be to deliver their monologue in character and have it videoed using any digital device.

Students will need to give the website a title and perhaps target it at a particular audience.

The videos would then be uploaded to the website which could be housed on the school intranet.

(ACEEN026) (ACEEN033) (ACEEN034)

Reporting of the Holocaust in the contemporary media

By the end of 1942, partly as a result of Karski’s testimonies, reports confirmed that the Nazis intended to exterminate all of European Jewry. Both in the United States and Britain, Jewish groups demanded that their governments take a stand against the atrocities. However, nothing of any consequence was put in place as governments argued for Roosevelt’s ‘rescue for victory’ approach advocating that all resources go to the war effort as the most effective way to rescue Jews from extermination.

The Museum of Tolerance’s Multimedia Learning Centre has published research on American Radio Coverage of the Holocaust which concludes:

American radio failed to provide a detailed and comprehensive account of the Holocaust. By its very nature, radio news programming is episodic and event-oriented, and sporadic reports about complicated events fail to make an impact on American audiences. Clearly, this limitation of radio applied to the failure to report the Holocaust during World War II. Moreover, broadcast guidelines and codes mandated routine objectivity and prohibited emotional controversy, thereby limiting the ability to report atrocities. In addition, the example of invented atrocity stories during World War I had made the networks fear unverified news stories. Thus, only as the war ended, were the crimes of the Holocaust fully verified; and only then did the sudden impact of revealed atrocities demand an emotional response. At that point, radio coverage became adequate.

The Bergson group published a series of advertisements in American newspapers to stir the conscience of citizens of the United States to action and mounted a huge pageant in New York City’s Madison Square Garden called, ‘We Will Never Die.’ The performance was dedicated to the 2,000,000 European Jews who had already been murdered. Hundreds of thousands saw the pageant as it toured America cities but it failed to make any difference to U.S. policy.

Have students read these advertisements and view the trailer of Reporting on the Times. They should also read an excerpt of the speech delivered to Parliament by the member for Kalgoorlie (located beneath the videos) on June 15, 1939 regarding Australia’s accepting only 5,000 European Jews a year for three years and consider:

- how language is used to persuade,

- how attitudes to an issue are represented in different contexts,

- how or whether attitudes and/or their representation change over time.

(ACEEN028) (ACEEN029)

Creative non-fiction

Café Scheherazade is not pure nonfiction. Working from the raw material of interviews students have watched on the Shoah website, Arnold Zable has ‘reshaped and re-imagined’ their accounts and Yossel, Zalman and Laizer are ‘composite characters’.

The author’s note however, asserts that ‘all dates and historical events have, wherever possible, been checked and authenticated’ and that ‘Café Scheherazade is based on actual events’ and Holocaust survivors’ interviews. The novel is a form of creative non-fiction.

Creative non-fiction is a term that is used to describe such writing as fictionalised biography, life writing, narrative or dramatised history writing. Yet the form has had a controversial history as can be seen by some of the statements below.

Student activity

Students can separate out the statements into those that would support the value of creative nonfiction and those that would not. They then could decide which side of the controversy they wish to take and position themselves on the pro- or anti- side of the room. Students from either side in turn advance an argument to support their contention trying to convince those on the other side to cross the floor. They may use examples fromCafé Scheherazade or any other creative nonfiction they have read or viewed to support their statements.

- Imaginary writing connects with realities wider than the events of the story.

- Writing labelled as ‘nonfiction’ should be true in every way.

- The reporting of actual events always involves some subjectivity.

- Using the tools of fiction writing helps the reader empathise with real people and their real experiences.

- Creative nonfiction does not convey authentic experience.

- In nonfiction there is a relationship of trust between writer and reader that there has been no conscious manipulation of the facts. Break that trust and the work is pointless.

- Autobiographies cannot be considered nonfiction as the writer is too subjective.

- The reader trusts the writer of creative nonfiction to research material thoroughly and present events with accuracy in the context of the story.

- Historical fiction is more fiction than history.

- Docu-drama or re-enactment of real events tells us more of the reality than documenting the facts.

- Nonfiction can never be pure fact.

- The survival or success of protagonists in creative nonfiction protects us from the harsh realities of the world and distracts us from the millions of others who did not succeed or survive.

- By blending fact and fiction, creative nonfiction distorts the truth.

Synthesising task

Creative writing

A story has no beginning or end: arbitrarily one chooses that moment of experience from which to look back or from which to look ahead. ― Graham Greene, The End of the Affair

Students could choose an incident from the news broadcast or from history and use creative approaches to convey their factual material. They could focus on one or more of the following strategies that have been discussed earlier in the unit:

- Conventional plot or dramatic structure,

- Characterisation,

- Point of view or perspective,

- Narrative voice and style.

Verifiable facts must remain true but fictional elements should be used to provide personal insights into the situation.

It would be helpful to offer some examples of how contemporary events may be enlivened by any of these approaches such as the hold-up of a store:

- as a thriller narrative;

- focalising the events through the eyes of one of the participants;

- telling the story from the perspective of a policeman on site/the mother of a participant etc;

- using a sympathetic/antipathetic narrator.

As a warm-up, students can play the storytelling game I was present using an actual event (scroll down to Game 3 in PDF).

(ACEEN032) (ACEEN033) (ACEEN034) (ACEEN035) (ACEEN036) (ACEEN037)

Rich Tasks: Representation of the Holocaust

Comparisons with other texts

There are many points of comparison of Café Scheherazade with other texts as there is now a great deal of Holocaust literature that can form a basis of comparison in terms of content and purpose. Well known to teachers are:

Written texts:

-

-

- Anne Frank, 1952: The Diary of a Young Girl

- Elie Wiesel, 1960: Night

- Mark Raphael Baker, 1997: The Fiftieth Gate

-

Multimodal texts:

-

-

- Art Spiegelman, 1991: Maus

-

Film:

- Claude Lanzmann, 1985: Shoah

- Steven Spielberg, 1993: Schindler’s List

- Edward Zwick, 2008: Defiance

These texts all take different approaches to the representation of reality, some with greater inclinations towards realism than others. Students could read or view a text of their choice from this list, or a substantial extract (10–20 pages for the written texts) and consider:

- What aspects of the text convince us of the reality, or even authenticity, of the information?

- What aspects of style and form by their very nature arrange ‘reality’ into ‘art’?

- What is not/ cannot be represented? Why?

Representation of the Holocaust in film

Representation of the Holocaust in film has had a chequered history. Early examples such as The Diary of Anne Frank in 1959 is most notable for its message of hope at its end – deeply ironic given her death in Belsen soon after – and often read in terms of the indomitable nature of the human spirit. The 1961 film Judgement at Nuremberg, while containing some newsreel footage of the camps, is primarily a story augmenting the American myth of righting wrongs and bringing freedom and justice to the oppressed. These films convey issues around the Holocaust in terms of conventional story types. The Pawnbroker (1964), on the other hand, is more honest and can only express the anguish of the Holocaust in a silent scream – an image of the inexpressible.

In 1978 a television series entitled Holocaust became the catalyst for survivors to begin telling their stories. Perhaps they felt strong enough after more than 30 years or perhaps they noticed that people might listen. However, the series was heavily criticised by Elie Wiesel for trivialising the events, so initiating the debate about the morality of turning the Holocaust into art.

This has become a huge issue. Using Café Scheherazade as well as a selection of these other texts, students could discuss the tensions between:

- diminishing the scope and brutality of the Holocaust by representing it in an artistic form; and,

- a way of ensuring that it remains a testament to the suffering of victims and humanity’s capacity for wholesale cruelty and disregard of human life.

These questions could structure their discussions:

- Should the Holocaust be the subject of art?

- If not how can it be represented?

Another approach to representation of the Holocaust could be through Life is Beautiful. This film came under some heavy criticism for the inappropriateness of comedy existing within the imagined reality of the camps.

Students could discuss this representation of the Holocaust considering:

- the role of comedy in the film,

- the importance of fantasy and romance (knightly tales) to its meaning,

- to what extent the fantastic elements of the film declare that experience of the Holocaust, its scope and its horror, is unrepresentable.

This idea of the failure of representation could also be explored through the poem by Dan Pagis: ‘Written in Pencil in the Sealed Railway-Car’

Student reflection

Students could write a reflection on what they have learned about the nature of representation through studying texts dealing with the Holocaust. Their reflection should guide them towards considering the power and limitations of representation.

(ACEEN028) (ACEEN030) (ACEEN031) (ACEEN038) (ACEEN040)