Introductory activities

Introduction to the multi-genre research paper: Rich assessment task 1

Throughout the unit students develop and build on a multi-genre research paper focusing on a person, idea, trend, time period, event, movement, viewpoint, thing or place that connects to a specific aspect of public language arising from their study of Death Sentence. This type of research paper combines imagination, analysis and experience and the activities in the lessons are designed to build the required skills and understandings.

Tom Romano, a proponent of this model, states in his book Fearless Writing that a multi-genre research project is ‘not an uninterrupted, expository monologue nor a seamless narrative. A multi-genre paper is composed of many genres and sub-genres, each piece self-contained, making a point of its own, yet connected to other pieces by theme and content and sometimes by repeated language, images and genres. A multi-genre paper may also contain many voices, not just the author’s. The craft then – the challenge for the writer – is to make such a paper hang together as one unified whole.’ (page 8)

A multi-genre paper has characteristics that resonate with a study of language and in particular Watson’s Death Sentence: The Decay of Public Language, including:

- combinations of texts

- a persistent argument

- examples drawn from historical and more recent contexts

- the inquiry process

- the intersection of personal experience and research

- a call to action

Activity 1: Why does language matter?

This and all the following activities provide a link into the multi-genre research paper (rich assessment task 1). This first one introduces some possible areas for exploration that students may wish to pursue in their research project. The statements in the half-sentence activity that follows could provide directions for research and possible unifying threads for their discussions.

In this activity students explore why language matters and should matter. Remind students that while not everyone studies language in a formal way, we all have views and perspectives about language. Language is central to human existence and daily life and we need to think carefully and precisely about language. Norman Fairclough argues that a ‘critical awareness of language . . . arises within the normal ways people reflect on their lives as part of their lives’. He states that the ability to understand how language functions, to think about it in different ways, is crucial to understanding society and other people. Understanding language is not about being accomplished, intelligent and doing well in school; there is much more at stake. Fairclough argues that to understand power, persuasion and how people live together, a conscious engagement with language is necessary. That is, critical thinking about language can assist in resisting oppression, protecting the powerless and building a good society (The Language, Society and Power Reader, p. 54). Both the quotation from de Saussure and the statements below could be research starters for the student research paper.

Step 1:

Display the discussion provocation below and invite students to brainstorm their responses in small groups. The techniques listed below could be explained and modelled to the class; students could choose an approach or two that they would like to try, or the teacher could allocate techniques to different groups.

‘In the lives of individuals and societies, speech is more important than anything else.’

(Ferdinand de Saussure)

What do you think?

Brainstorming techniques

- Substitution: where students substitute other aspects of living they think are more important than anything else.

- Combination: where students combine two aspects from the statement that they see as synergistic.

- Adaptation: where students select an aspect of the statement and adapt it. Recent technological developments in social media might be interesting here.

- Modification or distortion: where students select an aspect of the statement for exaggeration and explore its effects.

- Putting an aspect of the statement to other purposes: where students consider which aspects of the statement could be used in a different situation.

- Elimination: where students eliminate an aspect of the statement and reflect on the changes that result.

- Reverse or rearrange: where students re-order the statement and look at the effects.

After exploring the statement in groups, invite students to select three different findings they have discovered in this process and record these for later sharing.

Step 2:

Explain to students that they are going to explore some other statements about language using a sentence matching activity (PDF, 120KB). A number of statements about language, some referenced in Death Sentence and others drawn from a variety of texts, are given to students. These statements are divided in half and distributed to students who then proceed to find their match. This activity actively develops students’ speaking and listening skills.

After matching the sentence halves correctly, students:

- decide whether and why the halves match

- discuss what aspects of language the statements value.

Students return to their seats and, as a whole class, discuss the implications of the statements and how they link to de Saussure’s. Display these observations for students, in the classroom or on a blog or wiki.

Link this discussion to the notion of language and purpose and ask students to explain how their statements link to purpose. David Crystal in How Language Works: How Babies Babble, Words Change Meaning and Languages Live or Die, identifies the following range of purposes that could be used as starting points:

- expressing emotion

- expressing rapport

- expressing sounds

- playing

- controlling reality

- recording facts

- expressing thought processes

- expressing identity

- meeting technological demands

(ACELA1565) (ACELY1749) (ACELY1752) (ACELY1754) (EN5-7D) (EN5-8D) (EN5-2A)

Activity 2: Why does public language matter?

(Link to the multi-genre research paper: This activity introduces the idea of power and language. Students also respond to different texts and textual forms that they could include in their projects.)

Through a workstation learning activity, students will develop an understanding of what public language in written, spoken and visual forms actually is, and what it says about individuals and society.

In the introduction to Death Sentence: the Decay of Public Language Watson writes: ‘Public language is the language of public life: the language of political and business leaders and civil servants – official, formal, sometimes elevated language. It is the language of leaders more than the led, the managers rather than the managed. It takes very different forms: from shapely rhetoric to shapeless, enervating sludge; but in every case; but in every case it is the language of power and influence. What our duties are, for whom we should vote, which mobile phone plan we should take up. In all these places the public language rules. As power and influence are pervasive so is the language: we hear and read it at the highest levels and the lowest. And while it begins with the powerful, the weak are often obliged to speak it, imitate it.’ (page 1) These activities orient students to the ways language shapes all our lives.

Step 1:

Provide students with a range of different textual examples of public language at work in the world by arranging computer workstations around the classroom. Each workstation has displayed:

- a different type of text such as a comment, article, sports interview, speech radio, interview, protest speech, declaration of war, poem, announcement, advertisement, website and image. Suggested weblinks are listed below

- these focus questions (PDF, 108KB) displayed on the computer

- a place for collaborative comment such as a mini-whiteboard, blog or notepad. This should have written on it the question: Shapely rhetoric or shapeless sludge?

Workstation texts:

While some of these would need regular updating to ensure currency, the prompts could be adapted to different texts.

- Comment: Rosalie Kunoth-Monks

- Article: Richard Flanagan

- Sports interview: Nick Cummins

- Speech: Australian Chief of Army, Lieutenant General David Morrison AO

- Radio transcript: Alan Jones and Malcolm Turnbull

- Protest speech: High school student 1970

- Declaration of war: R.G. Menzies 1939

- Poem: Mutant Proverbs

- Image: Young, Lazy and Driving us Crazy

- Website: Sea Shepherd

- Advertisement: The Australian: Mining Boom

- Announcement: The War on Terror

Step 2:

Choose one of the texts above and preview it with students using these prompts for class discussion:

- What is the text about?

- What is notable about its use of language?

- Do you consider the language to be official, formal or informal?

- In what ways does the language used exert influence or power?

- Do you think this language is imitated in society?

- Do you consider the language used to be shapely rhetoric or shapeless sludge? Why?

Step 3:

Direct students to visit three or four different workstations instructing them:

- to read and view the text and record their responses to the questions

- record an opinion about the use of public language in the text on the mini-whiteboard, blog or notepad.

Step 4:

As a class, classify whether the texts might relate to:

- language and identity

- language and politics

- language and the media

- language and vision

- language and management/marketing

Step 5:

Working in pairs or small groups, invite students to synthesise the comments on the texts to evaluate whether the readers saw the texts as illustrating either shapely rhetoric or shapeless sludge and present these findings to the class.

Step 6:

Display for students Watson’s statement ‘Public language is the language of public life.’ Ask them to write down what this means in their own words.

(ACELA1564) (ACELA1565) (ACELT1639) (ACELT1641) (ACELT1812) (ACELY1752) (ACELY1754) (EN5-5C) (EN5-7D) (EN5-8D) (EN5-3B) (EN5-2A)

Activity 3: Memorable experiences of public language

(Link to the multi-genre research paper: This activity relates public language to personal and literary experience. The exposition could be included as one of the initial texts to be included in the paper and these discussions could form the basis of other imaginative or analytical writing.)

In this activity students recall instances of public language that create indelible moments. Linking discussion to the previous texts, remind students of de Saussure’s comment which essentially states that how we speak determines who we are as individuals and who we are as a society. Introduce students to the concept of indelible moments (Fearless Writing, pages 68-69) by explaining to them that such moments are often associated with vivid images and exact memories of words. Romano emphasises that indelible moments are often laden with emotion and complex meaning and that they can be defining moments.

Step 1:

Tell the students about an indelible moment in your life where public language has affected you:

- recreate the detail of the place, characteristics of the speakers, the emotion and reaction that transpired

- emphasis the moment, the image, the short space of time.

Step 2:

Share with the students an example from literature. Porter’s poem Mutant Proverbs might be particularly useful here.

Step 3:

Invite students to deliver a sixty-second anecdote recreating an indelible moment where public language has strongly affected them.

(ACELA1564) (ACELA1571) (ACELY1750) (ACELY1751) (EN5-5C) (EN5-3B) (EN5-1A) (EN5-2A)

Activity 4: Planning the multi-genre research paper

(Link to the multi-genre research paper: Students commence preliminary exploration of ideas.)

In this activity students reflect on possible areas for their research paper. After the answers are completed, students should revisit them two or three lessons later to revise their initial thoughts. Students could present a brief overview to the class after this review.

- Name a possible aspect of public language for investigation.

- What do you already know about the topic?

- What do you want to know about the topic?

- What sparked your interest? List some aspect of public language.

- Make a list of as many questions as possible of things you would like to know about the topic.

- Which kinds of texts will you create or include

- Create a bibliography.

(ACELY1757) (ACELY1776) (EN5-2A)

Rich assessment task 1: The multi-genre research paper

This activity sets down the requirements for the paper. Please refer to the rubric (PDF, 116KB).

Students will develop a multi-genre research paper focusing on public language. This could involve a person, idea, trend, time period, event, movement, viewpoint, thing or pace connects to a specific aspect of public language arising from their study of Death Sentence. The research paper is a creative text in that it includes students’ own created compositions which could be imaginative or analytical or both. The initial framing of the topic is critical to deeper thinking, richer writing, and more powerful performances. It could be presented as a multimodal or print text.

Possible aspects of public language that students might explore or include:

- the nature of public language

- language and national identity

- language, politics and power

- language, truth and the media

- rhetoric and vision

- language and heritage

- the language of marketing

- the language of management.

Reading requirements

The required reading texts are:

- Don Watson’s Death Sentence: The Decay of Public Language and George Orwell’s ‘Politics and the English Language’, in Inside the Whale and other Essays

- articles including primary sources such as interviews, first-hand accounts, observations, speeches, other writings on language

- reliable internet sources.

Mandatory genres to be included in the paper:

The number and nature of the genres to be included in the multi-genre research paper will be determined by the resources, interests and abilities of the class and the adaptations the teacher wishes to make in the teaching and learning cycle. In designing the research paper there are some specifics which give it a strong framework. The multi-genre research paper should include:

- an expository piece that names the argument a student presents, contextualises the viewpoint in the texts included and clearly establishes a unifying element that says something about the nature of public language. This would be the introduction (about 300 words).

- an endnote or a reflection statement where students review what they have come to understand about the nature of public language

- texts created by the students

- texts gathered (and annotated) by students

- genres that demonstrate their responses to Watson’s Death Sentence: The Decay of Public Language and Orwell’s ‘Politics and the English Language’.

A suggested list of genres follows:

- poetry

- examples of stories

- examples of myths, fairy tales and tall tales

- examples of rhetoric

- examples of polemic

- examples of nonfiction

- examples drawn from the media

- an appropriated text

- examples of visual texts such as images, multimedia, sound grabs, annotations of texts that link meaning, public language and specific rhetorical techniques

- a bibliography

Other examples can be found here. The actual number of required texts could be adapted to the needs, interests and prior learning experiences of the class.

Unifying elements

There must be unifying elements such as:

- repeated images, symbols or motifs

- repeated phrases

- a detail used as a basis for elaboration

- metaphors.

For students who prefer the multimedia paper:

Documentary story-telling in some ways approximates a multi-genre research task in that it combines different texts and experiences related to a single concept. The documentary site Unspeak provides examples of public language at work. Students could create a multimedia paper, which in some ways is a documentary. This could include:

- archival footage

- photos

- interviews

- short movies

- music

- sound

- combinations of narrative, persuasion, argument

- narrative perspective

- expert opinions.

(ACELA1564) (ACELA1565) (ACELA1569) (ACELA1571) (ACELT1639) (ACELT1641)

(ACELT1642) (ACELT1643) (ACELT1814) (ACELT1815) (ACELT1644) (ACELY1749)

(ACELY1754) (ACELY1756) (ACELY1757) (EN5-5C) (EN5-7D) (EN5-3B) (EN5-8D) (EN5-2A) (EN5-6C) (EN5-1A)

Close Reading

The close reading activities that follow are structured around a series of DARTS (direct activities, related to texts) reading strategies. These encourage students to read a text carefully, to go beyond literal comprehension and to think about what they read. These practical and collaborative activities could be used in a number of ways including:

- a sequence of lessons focusing on Death Sentence: The Decay of Public Language

- a series of mini-lessons interwoven with the development of the multi-genre research task

- learning activities for class groups

- teaching strategies that can be adopted to different texts.

Activity 5: Polemics and plain speaking

(Link to the multi-genre research paper: Students need to make specific reference to this text in their research paper. They can use Watson’s text or they can refer to some of the other texts he used in Death Sentence as examples of polemic.)

Through this activity students will become familiar with the introductory premise of Death Sentence: The Decay of Public Language and with aspects of Watson’s style. By re-presenting the opening paragraphs to students, sentence by sentence, students can reflect on the initial framing of public language as a concept and the voice in Watson’s polemic.

Step 1:

Introduce the term polemic to students. Display for students two possibilities offered in the Macquarie Dictionary:

- a controversial argument; argumentation against some opinion, doctrine etc.

- someone who argues in opposition to another; a controversialist

As a class, make a list of people who might qualify as polemicists. Students could draw on some of the texts they have already encountered in their study, other speeches, essays, bloggers, social commentators. Polemics also occur in social institutions such as schools – perhaps the principal’s address could be a fruitful site for polemics. Discuss with the class how these examples of polemic align with the definitions.

Invite students to research some quotes from these polemicists and analyse:

- the nature of the controversy

- the attitudes held on both sides of the controversy

- how these attitudes are evidenced in the tone of the quote

Step 2:

Read to students the opening paragraphs of the introduction of Death Sentence: The Decay of Public Language.

- Display for students the extract from the insurance company newsletter from the first page of the handout and ask them to read it in pairs. They could read it aloud to each other

- Students discuss what they think the newsletter is saying and rewrite it more simply

- As a whole class, make a list of the words that they think are unnecessary

Step 3:

Display for students the remainder of the opening paragraphs sentence by sentence. Ask students to write down anything they notice that they think frames the viewpoint. Class discussion might include aspects such as:

- the essential point students see in each sentence

- direct address to the reader

- formal and informal diction

- the use of italics

- word play

- syntax

- the overall argument

Step 4:

Invite students to read and discuss in pairs, and subsequently as a whole class, the remainder of the chapter, which discusses the relationship between public language and marketing, managerialism, politics and war. This would be another place where an episode of Unspeak could be shown.

Step 5:

As a concluding activity ask students to write a description of the controversy about public language that Watson poses and the attitudes evidenced in the tone of the writing.

(ACELA1570) (ACELT1641) (ACELT1643) (ACELY1752) (ACELY1754) (EN5-3B) (EN5-8D) (EN5-2A)

Activity 6: Weasel words

(Link to the multi-genre research paper: This activity enables further close study of Death Sentence and examples of some different genres such as media, website, announcements, mission and vision statements.)

This DARTS activity provides opportunity for students to consider how the language of management is used in representing our society and what they think about that. Eva Cox, human rights activist, has made the point repeatedly in recent years that as a country we need to consider ourselves as a society, not an economy. How we see ourselves and others is demonstrated in the language we use to describe our shared human experience. Watson worries about how corporate-speak leads to obfuscation or a loss of meaning. The discourse around disability provides examples for you to use as an introduction to this aspect of Watson’s discussion.

Step 1:

Present students with an overview of some of the key points Watson raises on the use of corporate language including:

- the fact that it is seeping into private conversation

- its inappropriate use

- its limited capacity for complex or uncertain meanings

- its mechanistic quality limits the need to think

- how marketing shapes our language.

Display for students this list of words and ask them to suggest contexts for the story in which they might be contained.

| promote independence | service user choice |

| purchase your own care provider | fairer charging policy |

| transitioned | person-centred plan |

| case | value |

| transparency | accessing the community |

| current placement | increasing independence skills |

| positive behaviour team | challenging behaviour |

| empowered | circle of support and influence |

| person-centred plan | inappropriately obsessive |

| challenging boundaries | lacking mental capacity |

Step 2:

Invite students to read this article, Viewpoint: 10 jargon phrases used for my autistic son, and consider these questions:

- What is the author’s intention?

- Does the author appeal to our logic or emotions, or both?

- Does the author address any opposition to his views?

- What is the sub-text to the article?

- How is language used in this article? Consider tone, voice, diction.

Step 3:

Divide the class into groups of four and ask them to choose two extracts from pages 8-44 listed below. Taking one of the two chosen extracts, students work in pairs to devise questions for the other students to answer.

- From Parrots, when they are separated from their flocks . . . to liability for the language to be limited. (pp. 9-10)

- From There have been signs of decay in the language of politics . . . to like the sections of a prefabricated henhouse. (pp.13-15)

- From This blurring of the corporate . . . to And it probably is, at the end of the day. p. 17)

- From If in your professional life you want to understand your fellow human beings . . .to customer shall not perish from the earth. (pp. 35-26)

- From Corporate leaders sometimes have good reason to twist their language into knots . . . to enhance sustainable growth for the benefit of all the stakeholders. (pp. 35-36)

- From At Optus we are paving the way for better . . . to This language really works!(pp.38-40)

- From The buzz word is the corporate equivalent . . . to are we much enlightened by it.(pp. 43-44)

Each group reports orally to the whole class explaining the extract in their own words and drawing links to the overview offered initially by the teacher.

Optional steps:

Supplementary learning activities that could be undertaken with a class or as additional research include:

- Rewriting bureaucratic speak in a more truthful way. (The website Weasel Words provides recent examples.)

- ‘Rescue a word’: as a class, determine a word or expression from contemporary usage that is being used and abused and is, therefore, in need of rescue.

- Reading the mission and vision statement of the school and assessing its accuracy and relevance and suggesting any possible changes.

- A survey of mission and vision statements developed by schools, and published online, to test how the language of marketing and business-speak have seeped into our language. This could be followed by a rewriting.

(ACELA1564) (ACELA1565) (ACELY1749) (ACELY1750) (ACELY1751) (ACELY1752) (ACELY1754) (EN5-5C) (EN5-7D) (EN5-8D) (EN5-1A) (EN5-2A)

Activity 7: Language and representation (how to avoid sludge)

(Link to the multi-genre research paper: Students need to make specific reference to George Orwell’s ‘Politics and the English Language’ in their research paper. This activity also promotes analysis of language techniques and possibilities for unifying elements.)

Throughout Death Sentence: the Decay of Public Language Watson offers advice on various aspects of language. In this jigsaw activity students examine some of Watson’s and Orwell’s remarks about the qualities of clear writing and, after discussion, devise and agree upon a set of writing rules for the class.

Step 1:

- Ask students to comment on what Watson sees as sludge and whether they agree.

- Elicit from students the possible meaning of the word barbarous and ask them to consider and explain how writing could be barbarous.

- Display for students Orwell’s rules for writing as shown below and ask them to apply these to one of the examples of sludge cited by Watson (for examples see pages 65, 83, 86). Students write a paragraph analysing how their selected examples violate the rule they have chosen from Orwell’s rules.

But one can often be in doubt about the effect of a word or a phrase, and one needs rules that one can rely on when instinct fails. I think the following rules will cover most cases:

(i) Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

(ii) Never use a long word where a short one will do.

(iii) If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

(iv) Never use the passive where you can use the active.

(v) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

(vi) Break any of these rules sooner than say anything barbarous.These rules sound elementary, and so they are, but they demand a deep change of attitude in anyone who has grown used to writing in the style now fashionable. One could keep all of them and still write bad English, but one could not write the kind of stuff that I quoted in these five specimens at the beginning of this article. I have not here been considering the literary use of language, but merely language as an instrument for expressing and not for concealing or preventing thought.

From Politics and the English Language by George Orwell

Step 2:

Allocate students to work in ‘home’ groups of four–five students. Each student in the group is given one of the aspects of language listed below as a prompt for investigation.

Students are reformed into ‘expert’ groups. Once in the expert groups students research their chosen aspects of language. They should:

- establish a definition for the language concept

- find examples cited in Death Sentence: the Decay of Public Language

- find specific quotes that represent the advice Watson suggests. (This could be drawn from either his direct comment or the other texts cited as examples or advice.)

- find examples from contemporary Australian usage. (Rich fields for exploration would include the media, sport, social institutions like schools, churches and community organisations.)

Students return to their home group and teach the group their chosen aspects of language.

Aspects of language:

Clichés

A French word, ‘cliché’ originally referred to a metal block used by printers to make multiple copies of engravings. Terry Pratchett said that ‘The reason clichés become clichés is that they are the hammers and screwdrivers in the toolbox of communication’. We often let them do the work for us, like machines. In fact, you could say that a cliché is an expression that does your thinking for you.

Euphemisms

‘It’s amazing – my parents call everything a discussion. If I were standing across the street, firing a bazooka at my mother, while my father was launching mortar back at me, and Jeffery was charging down the driveway with a grenade in his teeth, my parents would say we should stop having this public “discussion”.’ (Jordan Sonnenblick, Drums, Girls & Dangerous Pie)

Catchphrases

Stop the boats is a catchphrase. A catchphrase is a saying that catches on in public language and memory. Often they reduce complex ideas to facile statements.

Platitudes

A platitude is defined in the Macquarie Dictionary as ‘a flat, dull or trite remark, especially one uttered as if it were fresh and profound’. Somerset Maugham offers this example in A Writer’s Notebook: ‘She plunged into a sea of platitudes, and with the powerful breast stroke of a channel swimmer made her confident way towards the white cliffs of the obvious.’ The internet is a rich source of platitudes, although it can be ephemeral.

Grammar

In The Elements of Style Strunk and White write: ‘Write with nouns and verbs, not with adjectives and adverbs. The adjective hasn’t been built that can pull a weak or inaccurate noun out of a tight place.’

Step 3:

As a group students devise a set of rules to propose as a guide to clear writing. Each group displays its rules and the class, through discussion, adapts and/or adopts the rules as principles for clear writing (or how to avoid sludge) to be used in that class.

Discuss with the class possible unifying elements for the research paper suggested by this investigation.

(ACELA1569) (ACELA1570) (ACELA1571) (ACELT1642) (ACELT1643) (ACELY1757) (EN5-3B) (EN5-2A)

Activity 8: Rhetoric and vision (pages 67–139)

(Link to the multi-genre research paper: This activity promotes analysis of rhetorical effects and possibilities for unifying elements in the research paper.)

In this DARTS activity students explore the relationship between what is said in public language and how it is said. Throughout Death Sentence Watson discusses the relationship between public language, literary heritage and historical events and their connections to rhetoric. Rhetoric according to the ancient Greeks involved having something worth saying, arranging it, styling it, remembering it and delivering it. Each step is equally important. For students, two key ideas that will resonate with their own text production developed in this section are:

- the need to have something to say – vision (Death Sentence: the Decay of Public Language, p. 114)

- the understanding that in making speeches people seek an embrace with an audience – rhetoric (Death Sentence: the Decay of Public Language, p. 139).

Step 1:

Divide this section of the book into chunks for the class according to the historical examples it uses. For example:

- Pericles

- Henry Lawson

- Henry Parkes

- Robert Menzies

- John Howard

- George Orwell

- national occasions such as Anzac Day

- historical events such as the Al-Qaeda attack on 9/11

- comparisons to other international figures – Abraham Lincoln, Tony Blair, George W Bush

- representations in literature, for example Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar

Step 2:

Invite students to read a section of the text aloud and multiple times. In pairs students:

- highlight key words or phrases and underline important places and people

- circle words that are unfamiliar

- use context clues to help define these words

- look up the meaning of unknown words

- write synonyms for these new words in the text.

Step 3:

Students record their findings using these headings:

- section and page references

- what the section is about – its ideas

- a list of unfamiliar words and meanings.

Step 4:

Students break the text down into smaller chunks, for example:

- its key phrases

- examples that are particularly effective

- what it has observed about vision and rhetoric.

Step 5:

Students write a paraphrase of the chunks and display these for the class.

Step 6:

Display this statement by Michael Kirby published on the cover of Sally Warhaft’s Well may they say . . . Great Australian Speeches: ‘A great speech is public poetry. It casts a spell on the chosen audience.’

- Using this statement as the opening sentence to a structured paragraph, students assess their findings from their reading on vision and rhetoric.

- Encourage students to consider examples that negate as well as support this statement by Michael Kirby.

(ACELY1752) (ACELY1754) (ACELY1756) (EN5-8D) (EN5-2A) (EN5-1A)

Activity 9: Language, politics and power – what should a politician say?

(Link to the multi-genre research paper: Students need to make specific reference to rhetoric in their research paper and to deliver a presentation at the end of the unit.)

In this DARTS activity students reflect on the relationships between power, politics and language. Discuss with students the idea that leaders – politicians, sportspeople, public figures in a democracy portray a society to itself. What is acknowledged in public discourse shows who and what we should remember or forget, who should be included or excluded from the national body or hopefully what our vision for the future should be. In this activity students adapt a published speech to a different situation and context, appropriating its syntax.

Step 1:

Begin this activity by inviting students to individually read the below extract from Death Sentence (pp. 139-140) and construct an argument tree with the topic as the trunk and the arguments as the branches. Supporting evidence can be lateral branches from the main branch.

When people make speeches they attempt an embrace. They say to their audience, “you and me both”: we are for all practical purposes the same. Martin Luther King did it in sentences that swept his audience across the United States – “from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire . . . to the curvaceous slopes of California”, and many places in between. FDR did it, comparing the troubles of Americans in 1933 with “the perils which our forefathers conquered”. Pericles, Lincoln and Mark Antony all did it in their own way. It’s a universal device: it says we are all one, with one profound inheritance, and one ideal to live up to. Speechmaking is an exercise in welding people together by welding them to whatever it is they have in common, be it their landscape, their ancestors, their ambitions, even their language. Politicians rarely get to make speeches as far-reaching as Martin Luther King at the Lincoln Memorial; but they can say similar things when they open a pre-school in an outer suburb, or a medical centre in a country town. They can talk about the suburban frontier, that most common of Australian experiences. They can link a new housing estate to the nation’s history, and the nation’s values and the Australian dream. They can do the same in the country town, except here they will talk about rural values, and community values, and quite possibly the values of mateship and sticking together. And not for nothing our politician will be seen soon afterwards patting cows and dogs and babies – because, if he got his words right, that is what he has just done with the people. He has stroked them, comforted them, bonded with them; told them that far from being forgotten they are a priceless asset, part of the heroic national story and frequently on his mind.

Invite the students to form pairs and to share their representation of the argument in the text.

Step 2:

Show students some examples or extracts of political speeches such as John Howard’s Bali memorial speech, Michael Kirby’s 2002 address at the opening of the Gay Olympics, Julia Gillard’s misogyny speech or Tim Winton’s address to the Australian Parliament (text in green) in support of marine parks. Other examples can be found in Men and Women of Australia: Our Greatest Modern Speeches (ed. Michael Fullilove), Speaking for Australia: Parliamentary Speeches that Shaped the Nation (ed. Rod Kemp and Marion Stanton), Stirring Australian Speeches (ed. Michael Cathcart and Kate Darian-Smith), ‘Well May We Say’ : The Speeches That Made Australia (ed. Sally Warhaft).

Based on their understanding of the extract from Death Sentence and working in pairs, students analyse a speech responding to the prompt: How does the speech you have read relate to the idea that a speech says to its audience ‘you and me both’?

Step 3:

Students now move from pairs into groups of four to discuss their understandings. Display the chart below to support group discussion.

| Discussion activity | Conversation starters |

| Ask questions to clarify your understandings | Can you tell me more about . . .? Can you give me an example? Could you rephrase your statement that . . .? |

| Ask for reasons to support an idea | This reminds me of . . . because . . . I think this is true because . . . |

| Ask for evidence when something sounds inaccurate | I am not sure about that, can you show me where that idea comes from? Can you tell me why you think it is true? Another example that is different is . . . |

| Use ideas from others | I agree that . . . I noticed . . . as well |

As a class, discuss with students the rhetorical techniques that they have observed in the speeches including aspects such as:

- how the speaker related the speech to the lives of the audience

- how the speaker carried the audience on her/his journey in the speech – rhetorical questions, use of stress and emphasis, pausing

- how the speaker created tension – timing, structure, development, release of information, repetition

- how the theme of the speech was significant

- how the speech used language to create a powerful effect

- the balance of emotion and logic – evocative language, tone, imagery

- what these speeches had to say about who and what we as a society should remember or forget, who should be included or excluded from the national body or hopefully what our vision for the future should be.

Additional assessment task: oral

As a formal assessment task, students develop a two to three minute speech focusing on an aspect of Australian society. Students choose one of the speeches that they have listened to earlier and re-write it changing the story, the situation and context to fit one of the areas set out in the table below. Students maintain the tone, structure and syntax of the chosen speech; that is they imitate the style of the speech and speaker. Aspects of Australian society could also be drawn from these areas.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(ACELA1564) (ACELA1565) (ACELA1569) (ACELT1639) (ACELT1640) (ACELT1641)

(ACELT1643) (ACELT1815) (ACELT1644) (ACELY1749) (ACELY1750) (ACELY1751)

(ACELY1752) (ACELY1754) (EN5-5C) (EN5-7D) (EN5-3B) (EN5-8D) (EN5-6C) (EN5-1A) (EN5-2A)

Activity 10: Words and pictures

(Link to the multi-genre research paper: Students need to make specific reference to media and visual texts in their research papers. Students could also adopt Watson’s column layout for their research papers.)

In this activity student critically assess the relationship of visual text and words in a daily media publication such as the evening news or news item, a news website or a current affairs programme, a multimedia montage or week in review segment on television. In weaving his argument about the relationship of public language and representations of the truth in the media, Watson acknowledges the power of the image. After analysing these media texts, students write a paragraph, with an accompanying example, commenting on the relationship between words and image in the text they have read, heard or viewed. In this activity students experiment with developing a particular voice.

Step 1:

Read these extracts from Death Sentence with the students, pointing out to them that examples to support Watson’s argument are juxtaposed next to these comments.

- Television news purports to tell us what is going on in the world. It tells us, however, in much the same way that the word biscuits written on a biscuit jar, or gorilla written on gorilla cage, tells us about biscuits and gorillas. News on TV is not much more than signage – the current word for more than one sign; as in, ‘God sent Moses a piece of signage’ or, Moses had a signage event that empowered him going forward. Naturally, the TV news cannot tell us everything, but it is the principal medium of information for the masses, the crucial medium of government and politics – and, of course, the slickest of vehicles for marketing. (p. 61)

- In media, soundbites grow ever shorter and more tendentious, even if this also means they are misleading, inadequate or silly. TV news adopts a strange sentence structure to accompany images. It is, after all, a visual medium . . . where words and images compete, go with the image. (p. 62)

- Pictures rule: but words define, explain, express, direct, hold together our thoughts and what we know. They lead us into new ideas and back to older ones. In the beginning was the Word. It might help everyone a little if among the signage in the news room – or the party room, or any room where decisions that concern the nation’s life are made – there was one that quoted the writer Barry Lopez: ‘Take care for the spiritual quality, the holy quality, the serious quality of the language.’ (p. 65)

Step 2:

Explain to students that institutions such as news websites and the evening news have power because they contain information that people have chosen to convey to the people; they decide how much time or space they will devote to each item and control what news will be shared and whose perspective(s) is(are) going to be shared.

Show students an example from the evening news or a news website where words vie with images. As a class critically analyse this text. Prompts might include:

- Whose viewpoint is expressed in the news article?

- Whose voices are silenced?

- Whose voices are discounted?

- What might some alternative perspectives be?

- What does the image depict? Why?

- Who or what is missing from the picture?

- What does the image maker (videographer, photographer) want you to think?

- What might an alternative image show?

- How does the visual text relate to the spoken text?

As a class discuss:

- how the image combines with the written or spoken text to create meaning

- which elements carry the strongest meaning?

- whether the text is reliable.

Remind students about:

- the way Death Sentence is structured with examples of sludge and literary advice exemplifying the discussion

- the way Watson asserts his argument through the voice in his writing.

Ask students to write a short paragraph critically analysing the text they have read, heard or viewed in the style of Watson’s text.

- Choose an aspect of the text that combines words and images upon which they wish to comment.

- Choose one of the extracts above to use as a model for students to write a short paragraph.

- Choose an accompanying example to include as a side note.

(ACELA1564) (ACELT1815) (ACELT1644) (ACELY1749) (ACELY1752) (ACELY1754) (EN5-5C) (EN5-3B) (EN5-6C) (EN5-8D) (EN5-2A)

Activity 11: The book cover

(Link to the multi-genre research paper: Students need to make specific reference to visual texts in their research papers.)

Using the book cover as a stimulus, students reflect on whether they agree with the sentiments expressed in the book. Discussion prompts could include:

- What is the significance of the black cockatoo?

- How does the layout of the cover relate to the book itself?

- Do you think the claims made about the book are true?

- Are there any aspects of Australian society silenced in this book?

- Do you agree with Watson’s title that public language has been issued a death sentence? If so, who has issued it?

(ACELT1640) (ACELT1641) (ACELY1749) (ACELY1754) (EN5-5C) (EN5-3B) (EN5-8D) (EN5-2A)

Ways of reading the text

The language of social institutions shapes both national and individual identity. David Buckingham in his introduction to Youth, Identity, and Digital Media notes the essential ambiguity inherent in the word identity. Its derivation is from the Latin root idem meaningthe same. However, the notion of identity suggests similarity and difference. We think we possess, as individuals, identity – we are different one from another – and that this is in some ways a consistent phenomenon. However, when we consider concepts such as national identity we imply that our identity is shared with other people. Public language – the language of national identity, cultural identity, gender identity – descends on each of us as individuals and shapes how we see ourselves. In the activities which follow students analyse examples of texts, drawn from the wider world, that relate to public language and its influences.

Activity 12: Talkin’ ’bout my generation

(Link to the multi-genre research paper: Students need to include examples of personal experience in their research papers. These texts provide models for genres that could be included.)

Mark McCrindle and Emily Wolfinger write in Word Up that ‘we are all a product of our times, and heavily influenced by the culture, technology and social markers that were merging during our formative years’ (page 10). Public language reflects this in its representation of young people as Judith Bessant points out in her article Talkin’ ’bout a generation: understanding youth and change. Bessant warns of the dangerous use of cliché and catchphrases to depict individuals and society.

Step 1:

Invite students to make a list of words and phrases used to categorise their generation such as Zeds, Gen X, Gen Y and make a list of words commonly used in public discourse to portray them. Others that Bessant suggests: Millennials, DotNets, Gen Next, Lost Generation, Me Generation, Narcissistic Generation, Digital Natives.

Step 2:

As a class, discuss what this language suggests about them and why this may have come into being. Prompts might include:

- How is time referenced in these labels?

- What attributes of young people are suggested in these labels?

- What role does technology play? Is this justified?

- Does this language empower or disempower young people?

- What social identity does it create?

- Compare the different labels used to describe different generations and explore how the language positions different generations in the public discourse (adapted from Wordup (Pages 9-10).

| Born 1901–1924 | Born 1925–1945 | Born 1946–1964 | Born 1965–1979 | Born 1980–1994 | Born 1995–2009 | Born From 2010 |

| Federation Generation | Builders | Baby Boomers | Generation X | Generation Y | Generation Z | Alpha Generation |

Step 3:

Working in pairs, have students survey and read some newspaper articles that discuss Generation Z and compare the observations they offer. A simple internet search of terms such as news articles Generation Z will provide an interesting analysis even on the results page:

- Display a results page and have students list all the words that they see as positioning Generation Z.

- Ask students to classify these words according to their intent, for example critical, supportive, relating to technology, relationship characteristics.

Have students choose one article and analyse the assumptions that underpin its use of language:

- Whose message is represented in this article? Why?

- Who is the audience? What words or images or sounds suggest its age, ethnicity, class, profession, interests, etc.?

- What is the text of the message? What is the subtext of the message? How does this relate to public language about Generation Z?

- What assumptions underpin the lifestyle it presents?

- What groups of people does this message empower?

- Are there any gaps or silences in the article?

As a class discuss the social identity the article represents and whether students feel that they identify with this.

(ACELA1564) (ACELA1565) (ACELA1571) (ACELY1749) (ACELY1750) (ACELY1751) (ACELY1752) (ACELY1754) (ACELY1813) (EN5-5C) (EN5-7D) (EN5-3B) (EN5-8D) (EN5-1A) (EN5-2A)

Activity 13: Public language and politics

(Link to multi-genre research paper: Students synthesise their investigations through critical analysis. This will support skill development for reporting investigations and identifying unifying elements.)

In this activity students analyse how specific rhetorical effects shape all forms of public language from slogans through to parliamentary debate and formal addresses. Students reflect on the the standard of public language used and whether they feel it is appropriate.

Step 1:

Slogans, most commonly a feature of advertising, have increasingly infiltrated the language of politics. Display for students a list of political slogans used in election campaigns and ask them to explore patterns in the language such as:

- the use of the pejorative

- specific areas of word choice such as the language of fear, of belonging, with fear

- their syntax, whether they are commands, whether they have a finite verb

- representations of national identity such as a fair go for all

- the extent to which the slogans are genuine.

Slogans are commonly used to distill complex ideas and debates into one-dimensional propositions. Discuss with students some slogans used in current parliamentary debates such as:

- whether someone is a battler or a bludger

- whether someone is a refugee or a queue jumper or an illegal

- whether someone is a lifter or a leaner

- three word slogans such as stop the boats

- alliteration such as toxic tax

- wordplay such as real change for a change.

Ask students to choose one of the slogans they have observed and to write down what complex ideas have been distilled into this slogan. Students could:

- list the groups in society that are empowered and disempowered by the language used

- list reasons for or against the ideology behind the slogan

- explain how the ideology in the statement can be resisted

- create a debating statement for use in class, for example that the media controls the image of battlers.

Step 2:

Conduct a vote with your feet game.

- Ask the students to stand.

- Allocate opposite sides of the room to for and against.

- Display for students the debating statements they have created.

- Students vote with their feet according to their views.

- Ask one or two people from either side to explain why they voted that way.

- Give students the opportunity to change sides if they wish and ask what prompted the change.

Step 3:

Show students an extract from parliamentary question time and instruct students to note down any examples of colourful public language that strike them as being effective. This summary of former Prime Minister Keating’s contributions could be useful. Invite students to analyse and evaluate Keating’s use of public language as typified in:

- the points he made

- his invective

- use of figurative language

- reliance on idiom.

Step 4:

Using this resource from the Parliamentary education office in Canberra, conduct a parliamentary style debate.

As a concluding lesson, brief students regarding the context of the Redfern Address and invite students to watch it. Discussion prompts could include:

- the ways in which the speech calls our concern to indigenous rights

- how it uses structure and argument to keep thinking and feeling together

- the connotations of words and images

- the ways in which the speech uses story to deliver its message.

Step 5:

Display for students Auden’s remark (mentioned in Death Sentence) that: ‘Even politicians speak / truths of value to the weak’ and pose this question: Based on your encounters with Australian political language in this learning activity, to what extent does Auden’s remark reflect your experience?

(ACELA1564) (ACELA1565) (ACELA1569) (ACELA1571) (ACELT1639) (ACELT1640)

(ACELT1641) (ACELT1812) (ACELT1642) (ACELT1643) (ACELT1814) (ACELT1815)

(ACELY1749) (ACELY1750) (ACELY1754) (ACELY1757) (EN5-2A) (EN5-5C) (EN5-7D) (EN5-3B) (EN5-8D) (EN5-1A)

Activity 14: Parody

(Link to multi-genre research paper: These activities enable the development of skills associated with parody and appropriation.)

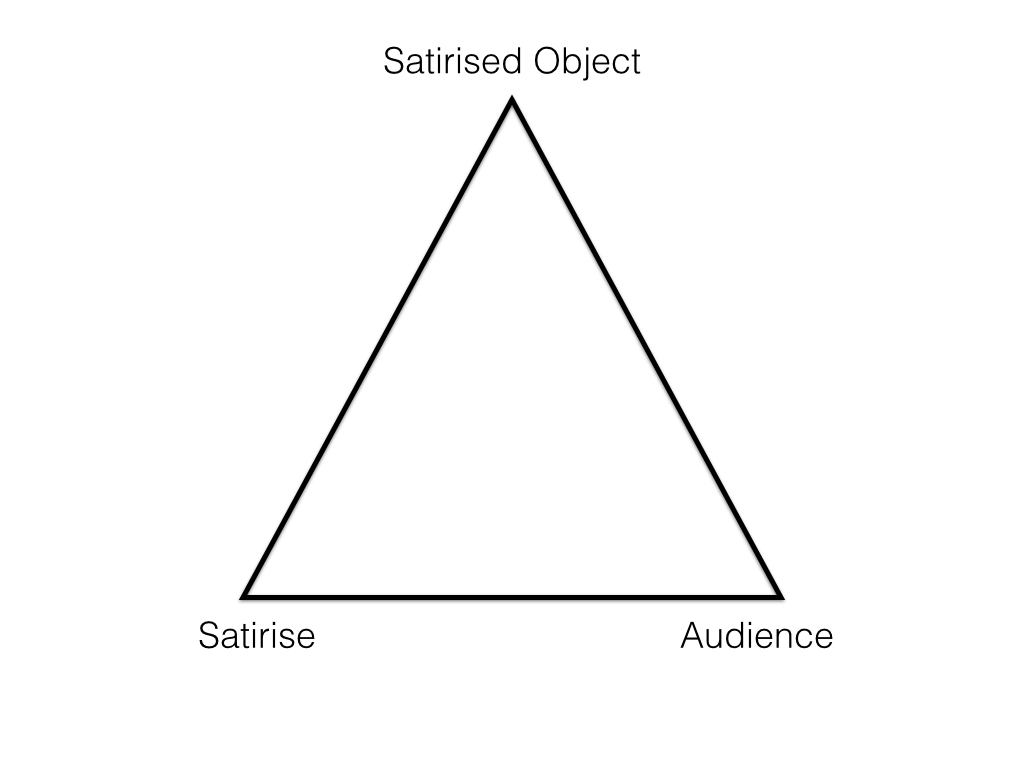

Public language provides opportunity for satire and parody. When there is a perceived absence of vision or the use of shapeless rhetoric in public discourse, people and events will be the objects of satire, and so for satire and parody to be effective people need to understand the relationship between satire, audience and the satirised object. In this activity students design a parody after studying the representation of an original text, place, person or object. It is through this approach that they appreciate the concept of a ‘critical distance’. Parody enables students to develop a heightened form of criticism and also a detailed knowledge of the text and its grammar and ideology. Students will then use one of the original texts to generate their own genre revisions and critical reflection on the issue under consideration. The sequence listed below is based on David Seitz’s discussion, Mocking Discourse: Parody as Pedagogy.

Step 1: Understanding satire and parody

Explain to students that they are going to create a parody and explain to them the relationship between satire, audience and satirised object using this diagram:

Show students some examples of satire such as political cartoons, television satire such as Clarke and Dawe’s The Use of English Language in Australia and this week’s News in Lego.

Invite students to name the audience for each of the previewed texts, the nature of satire used and the satirised object. Discuss with students elements such as the use of humour, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to expose and criticise people’s poor judgement, stupidity or vices.

Step 2: Developing critical distance

Invite students to form groups of three and agree upon a current public issue. Each member finds and brings to the group one to two opinion pieces on the issue. These should cover a range of views that represent the spectrum for the issue they have chosen.

Working in groups students then choose three texts, preferably opinion pieces, that refer to the same or similar events or person but from different positions or viewpoints. Students will summarise the issues and the ways language is used to show each author’s position. Opinion pieces could be drawn from interviews, social media, advertisements, essays and contributions to public debate such as parliament or speeches. Student summaries should include for each article:

- what the issue is

- what the text says about that issue

- what the author’s position is on the issue

- a brief list of the arguments offered and the rhetorical strategies used by each author.

Remind students that satire and parody arise from a close study of the original text, and as a class discuss their findings so far. Discussion prompts might include:

- What are the beliefs that underpin each article?

- How does each author define the issue differently? What is emphasised? What is silenced?

- How does the author’s background affect their discussion? Consider aspects such as age, class, political views, race, gender, religion.

- How do the authors use specific language effects or types of argument to present their views?

- Do these articles appeal to logos (logic), pathos (feelings) and ethos (ethics) and if so, where is the appeal strongest?

Step 3: Presenting the parody

Working in their groups, students now proceed to create their own parodies in the form of a commercial or public service advertisement. They should select three or four arguments or rhetorical effects from their three chosen texts to include in the parody of the chosen issue. Requirements for the parody include:

- acknowledgement of a clearly identified audience

- images and text for either a commercial or public service advertisement of between 30 and 60 seconds in length

- a transcript of the advertisement

- presentation through multimedia or role play.

Step 4: Genre revision and critical reflection

Working individually, students choose one of the opinion pieces and rewrite it in at least one different genre. Possible genres might include any of the genres listed in the outline of the multi-genre research paper.

After competing these adaptations students write a critical reflection focusing on comparisons of:

- the audiences for the original texts and the adapted text(s)

- the different tone of voice toward the issue

- the different arguments

- the different cultural assumptions

- the rhetorical strategies.

(ACELA1564) (ACELA1565) (ACELA1571) (ACELT1639) (ACELT1640) (ACELT1641)

(ACELT1812) (ACELT1642) (ACELT1643) (ACELT1814) (ACELT1815) (ACELT1644)

(ACELY1749) (ACELY1750) (ACELY1751) (ACELY1752) (ACELY1754) (ACELY1756)

(ACELY1757) (EN5-5C) (EN5-7D) (EN5-3B) (EN5-2A) (EN5-6C) (EN5-8D) (EN5-1A)

Presentation

The concluding sequence focuses on the final submission of the multi-genre research paper. There are three components: a presentation, a reflection activity and the final submission as a display. This assessment rubric (PDF, 116KB) could be used for both the presentations and the written paper, covering both receptive and productive modes.

Activity 15: Presentations

In this activity students present an aspect of their multi-genre research paper at a class conference called Unspeakable: Public Language? This simulation offers a number of forums for students to share an aspect of their work. Suggestions are listed below.

Prior to the class conference, determine which kinds of presentations students will use and group students accordingly. Allocate a group leader who will manage the group – for example sequencing presentations, keeping time limits, coordinating peer evaluations (PDF, 101KB) of the presentations.

Presentation suggestions:

- a debate using a topic such as the quality of public language determines how a society views itself

- readings of their own created texts to small groups

- a speech to the small group emulating a style they have observed

- parody of an aspect of public language

- presentation and explanation of a digital scrapbook

- interview or expert query

- sharing an anecdote

- slam poetry presentation

- presentations of visual texts or artefacts

- a partner presentation where two people co-present

- a panel discussion

- presentation of a multimodal task.

(ACELA1564) (ACELA1565) (ACELA1569) (ACELA1571) (ACELT1640) (ACELT1642) (ACELT1643) (ACELT1814) (ACELT1815) (ACELT1644) (ACELT1749) (ACELY1750) (ACELY1751) (ACELY1752) (ACELY1754) (ACELY1757) (ACELY1813) (EN5-5C) (EN5-7D) (EN5-3B) (EN5-2A) (EN5-6C) (EN5-8D) (EN5-1A)

Activity 16: Reflection activity – creating endnotes

Prior to the final submission, invite students to reflect on the decisions they have made throughout the research process. Questions could include:

- Why did you choose your topic?

- What interesting facts have you learned about your topic?

- Why did you choose these genres?

- What was the most difficult thing about the research?

- What was the most difficult thing about working on the genres?

- What do you feel you have learned about public language?

(ACELA1570) (ACELA1571) (ACELT1814) (ACELT1815) (ACELT1644) (ACELY1757) (EN5-3B) (EN5-5C) (EN5-6C) (EN5-2A)

Activity 17: Final submission

Publication of the research papers could take a number of forms:

- a gallery walk where students display their research paper complete with:

- project title

- project Idea (summary of main issue/task/purpose)

- content (summary of key standards/topics)

- genres

- Students move around visiting the projects and asking questions about their development.

Other possibilities:

- a showcase to other classes, parents, schools

- creating an archive of the research papers in the classroom

(ACELT1644) (ACELT1814) (EN5-6C) (EN5-5C)