Watch a short video on this text from the Books That Made Us series, available via ABC Education!

Introductory activities

Tapping into prior knowledge (e.g. content, expectations)

In this sequence students are introduced to the fictional autobiography, My Brilliant Career, its historical context and an overview of its content.

Completed in 1899 and rejected by local publishers, My Brilliant Career was finally published by Blackwood in Edinburgh in 1901, the year of Australian Federation. The novel has enjoyed a solid readership in Australia and now is firmly established in the Australian lit

Pre-reading activities: Understanding the period

Have students do a Google image search on such terms as ‘homestead/hut/women/men/children/Aboriginal/Australia 1890’, and choose three or four contemporary photographs from each category and print them in a photo album/enlarged in a frieze/enlarged as framed pictures around the room or loop them in a PowerPoint presentation on the class intranet.

Looking at all the pictures speculate about what it could have been like as a woman:

- dressed in these costumes doing physical work/in the heat/engaged in social activities

- living in these dwellings

- encountering racial and social difference.

Students refine these notions by researching the effects of the Australian Depression and long drought of the 1890s to consider such issues as:

- the lives of the rich and the poor

- the roles of men and of women

- the nature of class, race and ethnic distinction

They should make notes on these issues to tag these aspects of the novel as they come across them in their reading.

Understanding present values

Students can consider the following statements and whether they agree or disagree and then share this in a class discussion.

- Life was tougher then for women.

- Women should be allowed to choose a career over marriage.

- It’s okay not to have a career.

- Romance is overrated.

- Lack of money is the greatest problem we can face.

- You should never have to make the choice between marriage or career.

- Education is the only way out of economic hardship.

- It’s tougher living on the land than in the city.

What’s your perfect career?

Students can work in pairs to interview each other asking:

- If you had the choice and the ability what would be your idea of a brilliant career?

- Why would you like this career?

The careers can be placed on a wall chart with the title: Brilliant careers in the 21st century.

Students can view the chart and comment on the types of careers people aspire to. Students may want to consider how many of these careers wouldn’t have been possible in the past or accessible to women.

Predictions

Ask students in groups to make predictions about what the novel will be about, based on:

- the blurb on the back of the book

- the images and ideas gained from their research and discussion

- the list of chapter headings

Predictions could include such elements as:

- the genre of the novel

- the nature, values and interests of the heroine

- the language of the novel

- the kinds of complications that may arise

- its central conflict

- possible resolutions of the conflict

Personal response on reading the text

While reading the novel

Have students write a reading journal of their personal responses to and reflections on the novel as they read. Their entries can be in motivated by:

- points where they identify with Sybylla and those where they are repelled by her, and why

- situations which engage their interest and those that do not, and why

- sections where they gain insight into the way of life at the time and what these insights are

- points where their own values are challenged and how.

After reading the novel

Students complete their reading journal with a personal reflection on what they have learned about:

- what the novel is about

- what they understand in the novel and aspects about which they have questions

- how they respond to novels of this kind

- their understandings of the period that have been challenged or confirmed

- how their own view of the world is altered or reinforced by their reading.

Outline of key elements of the text

After reading the novel

Students will need to work with the content of the text in some detail. This can be done by dividing the text into sections that fall broadly into the places where Sybylla lives:

- Chapters 1–8

- Chapters 9–16

- Chapters 17–26

- Chapters 27–32

- Chapters 33–38

Groups can take charge of one of these and furnish such information as:

- A plot graph with a timeline of the action (x axis) mapped against the emotional intensity of the event (y axis).

- Key quotations reflecting:

Synthesising task/activity

Summarise your group’s findings for the others through a PowerPoint presentation defending the position that your section of the novel is the most significant to:

- Sybylla’s story

- your understanding of lives in rural Australia at the end of the 19th century.

The PowerPoint file should be posted on the class intranet along with supporting details of the group’s research.

(ACELR040) (ACELR045)

The writer’s craft

Structure and setting

The story is developed chronologically beginning from Sybylla’s first recollection of her father when she was three years old. The second chapter moves to when she was 9 years old. Her father’s misguided dreams motivate the family move to Possum Gully.

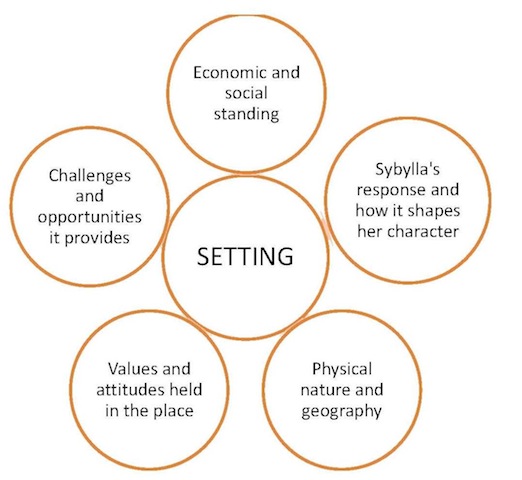

Setting provides structure for the novel allowing us to see Sybylla and her development in different places. Each setting creates a space for different possibilities. The settings are varied and contrasted.

Student activity:

- In groups choose one of the settings of the novel and find key descriptive passages. Comment on how Miles Franklin uses language to convey a sense of place.

- Develop a concept map (see example below) or some other graphic to consider how your chosen setting affects Sybylla and shapes her character. Share your findings with your class.

Approach to characterisation

As with all textual aspects, the creation of character requires more than the words on the page. A reader constructs a character by drawing inferences from the information provided by the text including what a character does, says and thinks as well as by what the narrator and other characters say and think about him or her. These inferences, drawn from our experiences of life and of other characters we have met in texts ‘flesh out’ the gaps in the data to create an imitation of a person.

According to James Phelan, the creation of a character towards whom we can have a range of feelings and attitudes is achieved through three components:

- mimetic (how a character can be suggestive of a possible person)

- synthetic (how a character is known to be a textual construct)

- thematic (how a character can point to a larger significance beyond its own attributes).

These components operate to varying degrees depending on the type of text. So for example in post-modern texts, like Louis Sachar’s Holes, Gary Crew’s Strange Objects or the television sitcoms Scrubs or Malcolm in the Middle, there is more emphasis on the synthetic component, but in a realistic text, the synthetic component is made as unobtrusive as possible to encourage the reader’s immersion in the story and identification with the characters.

In what ways is the construction of Sybylla mimetic of a possible person? How plausible a person is she? What thematic significance does the character carry in terms of:

- The role of women?

- The place of class in Australian society?

- The development of what may be called the ‘Australian character’?

Narrative voice

From its epistolary prologue My Brilliant Career makes clear that this is a first person narration, ‘this story is all about myself’ and is addressed to, ‘my dear fellow Australians’. The novel at once claims an autobiographical status as well as a nationalistic position. Indeed the links between Stella Franklin, Miles Franklin and Sybylla Melvyn are very close and at some points too close for the author’s comfort; so much so that in 1910, Franklin withdrew the novel from circulation because ‘the stupid literalness with which it was taken to be her own autobiography startled and disillusioned then constrained her’ (Webby p. 350).

This situation gives us a clear invitation to explore the nature of narrative voice and question to what extent a reader could identify a first person narrator with the implied author or even the actual author herself. The task is made even more complex as Sybylla is not the most reliable of narrators, making assertions that are not borne out in the book.

Have students consider where on the authority scale the following passages from the text could sit and have them give reasons for their decisions. Discuss the results in class.

| Author Stella Franklin |

Implied Author Miles Franklin |

Narrator Sybylla Melvyn |

- ‘This is not a romance – I have too often faced the music of life to the tune of hardship to waste time in snivelling and gushing over fancies and dreams; neither is it a novel, but simply a yarn – a real yarn. Oh! as real, as really real – provided life itself is anything beyond a heartless little chimera – it is as real in its weariness and bitter heartache as the tall gum-trees, among which I first saw the light, are real in their stateliness and substantiality.’ (p. 3)

- ‘Do not fear encountering such trash as descriptions of beautiful sunsets and whisperings of wind. We (999 out of every 1000) can see nought in sunsets save as signs and tokens whether we may expect rain on the morrow or the contrary, so we will leave such vain and foolish imagining to those poets and painters – poor fools! Let us rejoice that we are not of their temperament!’ (p. 4)

- ‘We walked in perfect silence, Harold not offering to carry my little basket . . . the most thrilling, electric, and exquisite sensation known.’ (p. 161-2)

- ‘Enough of pessimistic snarling and grumbling! Enough! Enough! Now for a lilt of another theme . . . I am only a – woman! (p. 264-5)

- ‘The great sun is sinking in the west . . . Goodnight! Good-bye! Amen.’ (p. 265)

Use of parallels and contrasts

To clarify meanings and to give form and balance to its fictional world, My Brilliant Career, like many other novels, is shaped around comparisons and contrasts. Some reflect the economic harshness of the times Miles Franklin lived in such as:

- financial comfort and ruin

- drought and fertility

- work and leisure.

Student activity:

Chart these contrasts through the novel, selecting examples from the text and consider how they influence the development of the narrative. Other contrasts go deeper and give us insights into Sybylla’s character:

- dominance and subservience

- romance and reality

- ambition and constraint

and the nature of the society she lives in:

- male and female

- rich and poor

- Aboriginal and white

- established settler and immigrant.

Student activity:

Exploring pairs of binary opposition can uncover assumptions in the text.

- Find examples of these ideas in the text.

- Consider what they reveal about Sybylla and her society.

- Question the extent to which the attitudes revealed may be contrary to the expressed meaning of the text.

Language and style

Franklin’s writing has an energy and unpretentiousness that conveys the voice of the lively young girl that Sybylla is. Her yearning, elation, ebullience and despair are carried through the use of the language which is unadorned but flows with a natural elegance.

Students can annotate such passages as the following, noting:

- variety of sentence structure

- quality of the diction

- use of repetition

- balanced sentences

- use of imagery

and how these express Sybylla’s desire to be a part of the world of the arts.

Passage from chapter 5:

I say naught against the lower life. The peasantry are the bulwarks of every nation. The life of a peasant is, to a peasant who is a peasant with a peasant’s soul, when times are good and when seasons smile, a grand life. It is honest, clean, and wholesome. But the life of a peasant to me is purgatory. Those around me worked from morning till night and then enjoyed their well-earned sleep. They had but two states of existence – work and sleep.

There was a third part in me which cried out to be fed. I longed for the arts. Music was a passion with me. I borrowed every book in the neighbourhood and stole hours from rest to read them. This told upon me and made my physical burdens harder for me than for other children of my years around me. That third was the strongest part of me. In it I lived a dream-life with writers, artists, and musicians. Hope, sweet, cruel, delusive Hope, whispered in my ear that life was long with much by and by, and in that by and by my dream-life would be real. So on I went with that gleaming lake in the distance beckoning me to come and sail on its silver waters, and Inexperience, conceited, blind Inexperience, failing to show the impassable pit between it and me.

Passage from chapter 26:

Boxing Day had fallen on a Saturday that year, and the last of our guests departed on Sunday morning. It was the first time we had had any quietude for many weeks, so in the afternoon I went out to swing in my hammock and meditate upon things in general. Taking with me a bountiful supply of figs, apricots, and mulberries, I laid myself out for a deal of enjoyment in the cool dense shade under the leafy kurrajong- and cedar-trees.

To begin with, Harold Beecham was gone, and I missed him at every turn. I need not worry about being engaged to be married, as four years was a long, long time. Before that Harold might take a fancy to someone else, and leave me free; or he might die, or I might die, or we both might die, or fly, or cry, or sigh, or do one thing or another, and in the meantime that was not the only thing to occupy my mind: I had much to contemplate with joyful anticipation . . .

Yes, life was a pleasant thing to me now. I forgot all my wild unattainable ambitions in the little pleasures of everyday life. Such a thing as writing never entered my head. I occasionally dreamt out a little yarn which, had it appeared on paper, would have brimmed over with pleasure and love – in fact, have been redolent of life as I found it. It was nice to live in comfort, and among ladies and gentlemen – people who knew how to conduct themselves properly, and who paid one every attention without a bit of fear of being twitted with ‘laying the jam on.

I ate another fig and apricot, a mulberry or two, and was interrupted in the perusal of my book by the clatter of galloping hoofs approaching along the road.

Here Franklin communicates Sybylla’s anguish at her new circumstances at Barney’s Gap, how appalled she is by the complete lack of culture or refinement of the M’Swats and her need to draw a distinction between herself and them. Students could note how this is achieved through:

- what Sybylla says and what she narrates

- how the various voices are written

- the difference in style between Sybylla’s narration and her direct speech.

Passage from chapter 28:

The children sat in a row and, with mouths open and interest in their big wondering eyes, gazed at me unwinkingly till I felt I must rush away somewhere and shriek to relieve the feeling of overstrained hysteria which was overcoming me. I contained myself sufficiently, however, to ask if this was all the family.

‘All but Peter. Where’s Peter, Mary Ann?’

‘He went to the Red Hill to look after some sheep, and won’t be back till dark.’

‘Peter’s growed up,’ remarked one little boy, with evident pride in this member of the family.

‘Yes; Peter’s twenty-one, and hes a mustatche and shaves,” said the eldest girl, in a manner indicating that she expected me to be struck dumb with surprise.

‘She’ll be surprised wen she sees Peter,’ said a little girl in an audible whisper.

Mrs M’Swat vouchsafed the information that three had died between Peter and Lizer, and this was how the absent son came to be so much older than his brothers and sisters.

‘So you have had twelve children?’ I said.

‘Yes,’ she replied, laughing fatly, as though it were a joke.

‘The boys found a bees’ nest in a tree an’ have been robbin’ it the smornin’,’ continued Mrs M’Swat.

‘Yes; we have ample exemplification of that,’ I responded. It was honey here and honey there and honey everywhere. It was one of the many varieties of dirt on the horrible foul-smelling tablecloth. It was on the floor, the door, the chairs, the children’s heads, and the cups. Mrs M’Swat remarked contentedly that it always took a couple of days to wear ‘off of’ things.

With Harold’s second proposal, Franklin intensifies the language of romance. (note Franklins’ note to publisher about the little bit of romance contained in the novel in Section 4).

Passage from chapter 36:

He gripped my hands in a passion of pleading, as two years previously he had seized me in jealous rage. He drew me to him. His eyes were dark and full of entreaty; his voice was husky.

‘Syb, poor little Syb, I will be good to you! You can have what you like. You don’t know what you mean when you say no.’

No; I would not yield. He offered me everything – but control. He was a man who meant all he said. His were no idle promises on the spur of the moment. But no, no, no, no, he was not for me. My love must know, must have suffered, must understand.

‘Syb, you do not answer. May I call you mine? You must, you must, you must!’

His hot breath was upon my cheek. The pleasant, open, manly countenance was very near – perilously near. The intoxication of his love was overpowering me. I had no hesitation about trusting him. He was not distasteful to me in any way. What was the good of waiting for that other – the man who had suffered, who knew, who understood? I might never find him; and, if I did, ninety-nine chances to one he would not care for me.

‘Syb, Syb, can’t you love me just a little?’

There was a winning charm in his manner. Nature had endowed him liberally with virile fascination. My hard uncongenial life had rendered me weak. He was drawing me to him; he was irresistible. Yes; I would be his wife. I grew dizzy, and turned my head sharply backwards and took a long gasping breath, another and another, of that fresh cool air suggestive of the grand old sea and creak of cordage and bustle and strife of life. My old spirit revived, and my momentary weakness fled. There was another to think of than myself, and that was Harold. Under a master-hand I would be harmless; but to this man I would be as a two-edged sword in the hand of a novice – gashing his fingers at every turn, and eventually stabbing his honest heart.

It was impossible to make him see my refusal was for his good. He was as a favourite child pleading for a dangerous toy. I desired to gratify him, but the awful responsibility of the after-effects loomed up and deterred me.

‘Hal, it can never be.’

Student activity: Evaluating style

H.M. Green in the History of Australian Literature describes Franklin’s style as being `sometimes excruciating: stiff, clumsy, formal, full of lapses in English and melodramatic cliches’ (quoted in Sheridan p. 330). Use the four passages above and others of your choice to discuss Green’s evaluation.

Synthesising task

- In your groups, using the information you have worked through above, suggest, discuss and refine the themes of My Brilliant Career (remembering that a theme is a statement about an idea, not simply an abstract noun). Share these themes with the class and as a whole, settle on several key ones for development.

- In your groups take one of these themes and create a presentation on how this theme is developed through the novel.

- Use a jigsaw technique to form new groups which cover all the agreed themes of the novel. Present your group’s explanation of the theme to the others.

(ACELR38) (ACELR044) (ACELR045) (ACELR046)

Genre: romance or realism

The last decade of the 19th century was the first to see the majority of the white population in Australia native born and a growing market for Australian Literature. One of the most popular and influential publishers of Australian writing was the Bulletin (‘the bushman’s bible’) with its realist accounts of masculine life in the harsh but beautiful Australian landscape. Most frequently mentioned writers in this genre were Henry Lawson, Steele Rudd, Joseph Furphy, and ‘Banjo’ Peterson. This view of Australian literature of the time does not give sufficient recognition to writers with a broader palette such as the poet Christopher Brennan or women writers who tended to focus more on romance and the domestic sphere.

Remind students of some of the bush ballads they have studied in the past, or read selections from one of these and ask them:

- what features these have

- how they have shaped our idea of the ‘Australian character’.

Then, without telling the students where this extract comes from, read this section from Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (towards the end of chapter 23), a popular classic even at Miles Franklin’s time.

‘Then I must go: – you have said it yourself.’

‘No: you must stay! I swear it – and the oath shall be kept.’

‘I tell you I must go!’ I retorted, roused to something like passion. ‘Do you think I can stay to become nothing to you? Do you think I am an automaton? – a machine without feelings? and an bear to have my morsel of bread snatched from my lips, and my drop of living water dashed from my cup? Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! – I have as much soul as you, – and full as much heart! And if God had gifted me with some beauty and much wealth, I should have made it as hard for you to leave me, as it is now for me to leave you. I am not talking to you now through the medium of custom, conventionalities, nor even of mortal flesh; – it is my spirit that addresses your spirit; just as if both had passed through the grave, and we stood at God’s feet, equal, – as we are!’

Ask students:

- Which genre this extract exemplifies?

- What aspects of the extract lead them to this conclusion?

- What other features they expect of that genre?

- What struggle do they see in this extract?

Struggle is a major element in the novel, whether it is physical, intellectual, economic or class driven. In small groups students choose aspects of and extracts from the novel that illustrate the idea of the frontier struggle and others that illustrate the experiences of a romantic heroine. A good way to get coverage of the novel is through the jigsaw technique where ‘home’ groups are given a section of the novel to cover and then share these with other groups in the class.

Students consider such aspects of romance as the:

- sudden entry into the ‘fairytale’ world of Caddagat

- transformation from ‘ugly duckling’ to appealing young woman

- many declarations of love she receives

- romantic tension

- series of obstacles placed in the way of love

- miraculous restoration of Harry’s fortune

- fidelity in the face of temptation

- distracted lover left to wander the world

and aspects of realism such as the:

- detailing of daily grind

- steady decline of family fortune

- description of the effects of drought

- shortcomings of the men as romantic heroes.

In her preface to My Brilliant Career Miles Franklin asserts that ‘This is not a romance – I have too often faced the music of life to the tune of hardship to waste time in snivelling and gushing over fancies and dreams’. Classroom discussion focuses on questions of:

- whether this assertion can be borne out by the novel

- how successful Miles Franklin has been in creating a hybrid genre.

Parody

The title of the book is clearly sarcastic; indeed it was initially submitted for publication as My Brilliant (?) Career.

Students discuss:

- whether other sections of the book may be written tongue-in-cheek

- to what extent parts of the book may be considered parodic

- whether these sections parody romantic conventions or are simply the product of a young girl’s expectations or of an inexperienced writer.

Gender

The male/female binary opposition is often the source for a feminist reading of a text. While My Brilliant Career is an overtly feminist treatise, the introductory chapters on Sybylla’s father connect her to him in having aspirations beyond their status and show that this struggle to overcome expectations is not just a female one.

Sybylla Melvyn repeatedly bemoans her situation in life. She feels unable to drag herself out of the round of poverty into which her family has fallen due to her father’s business decisions and subsequent drunkenness. Her mother has no choice but to follow and struggle as best she can and through the deterioration of their circumstances, Sybylla’s own education is inadequate for anything more than menial work.

The feminist movement in the late 19th century was in its ‘first wave’ and the calls for reform of women’s plight were slender but strident, so strident that feminists were known as the ‘shrieking sisterhood’.

For them, the question of marriage was a serious one as women did not have the same rights as men within the marriage. Pregnancy was an almost constant condition and childbirth was frequent and dangerous. These comments from Woman’s Voice, a journal published in 1894 and 1895 in Sydney, give us a sense of the concerns of women activists at this time (quoted in Magarey p. 89).

- ‘We seem to be all agreed for the moment that among human institutions marriage is the completest failure.’

- ‘Enforced motherhood is the bane of hundreds of women’s lives today.’

- ‘The crux of social reform is the establishment of equal marriage and the individual responsibility of parents.’

- ‘The “question of compulsory motherhood” is the question that underlies the declaration of the rights of woman.’

In contrast to these serious issues, contemporary audiences would have been subjected to cartoons lampooning women who wanted suffrage. Students can search the internet for such cartoons and discuss how these positioned women.

Student activity:

Divide the students into groups to gather the following evidence from the text and consider them in the light of the quotations above.

- Sybylla’s statements about marriage and motherhood.

- Longfellow’s ‘The Slave’s Dream’, which Sybylla recited at the party in Caddagat.

- Sybylla’s interest in and talent for a career in the arts.

Collect this evidence on post-it notes around the room or in some other form accessible to all students. Have students either:

- Hot seat Sybylla about marriage and a career

OR

- Write an essay on how well the film My Brilliant Career depicts these ideas.

Social reading

Sybylla has a social conscience and is sympathetic to the plight of those victims of the depression forced to tramp through the bush seeking work or charity. At Caddagat it is her job to attend to the tramps and she takes their plight to heart, giving them extra rations and questioning what can be done to assist them. This attitude differed from Jay-Jay, Granny and from Harry who see the tramps as ‘a lazy lot of sneaking creatures, fed them, and thought no more of the matter’.

Sybylla’s generosity demonstrates her social ideals and she frequently comments upon the less fortunate, ‘thousands of our fellows – starving and reeking of disease in city slums’. This identification with and compassion for the poor is possibly because of a keen awareness of her own precarious social status threatened as it is by her family’s poverty. (This view of Sybylla’s sympathies and motivation can be contrasted with other perspectives on swagmen. Students could read Barbara Baynton’s short story, The Tramp later called The Chosen Vessel).

However, Sybylla’s sympathy does not extend to Aboriginals who are spoken of with disdain. In her ‘Special Notice’ at the beginning of the book she says: ‘Better be born a slave than a poet, better be born a black, better be born a cripple!’ She refers to Harold’s employee who collected the mail at Dogtrap as ‘Harold Beecham kept a snivelling little Queensland black boy as a sort of black-your-boots, odd-jobs slavey or factotum’, and writing her regular letter to her mother from Barney’s Gap: ‘Once a week I headed a letter “Blacks Camp”‘.

These were not unusual attitudes of the period and can be compared to disparaging comments about Orientals (turning ‘Turk’, scornful references to Harry as a ‘sultan’ who could have a ‘harem’ at his beck and call). The text constructs both Aboriginals and Orientals as the wild and oppressive ‘other’. Sybylla’s desire for her own independence and her liberal mindedness in regard to social equality of whites, does not rise above these ethnic prejudices which were ingrained in her society.

Because of Australia’s geographical position and in a bid to be seen as ‘western’, Australians have, until the second half of the 20th century, stood staunchly against the influences of Aboriginal culture and of the exotic East. At the time, this intolerance was seen as an aspect of respectability and moral rectitude, a bulwark against what was perceived as cultural degeneration. Sybylla, with her skin ‘whiter than the fairest blonde’, may well have progressive feminist and social attitudes but for her radicalism to be acceptable to a contemporary readership, needed to be seen as Australian through and through and someone who does not threaten the essential western nature of society.

An expression of nationalism

My Brilliant Career was first published in 1901, the year of Australian Federation, a conjunction that has led people to see the novel as a story of fledgling nationhood and nationalism. Certainly Sybylla utters many expressions of patriotism from her opening address, ‘My dear fellow Australians’ to her closing paragraphs in praise of her homeland and her compatriots: ‘I am proud that I am an Australian, a daughter of the Southern Cross, a child of the mighty bush’.

What greater acknowledgment of this national stance can there be than Henry Lawson’s declaration in his preface to the novel: ‘I saw that the work was Australian – born of the bush . . . the descriptions of bush life and scenery came startlingly, painfully real to me, and I know that, as far as they are concerned, the book is true to Australia – the truest I ever read’.

The enthusiasm of this nationalistic expression needs to be viewed in the light of a nascent recognition that Australia was not simply another Britain on the other side of the world but had its own character that was different from the mother country and most worthy in its own right. This can also be seen in the depiction of Harold Beecham, an Australian through and through, and Frank Hawden, the jackaroo ‘on work experience’ from England.

Student activity:

As a contrast to the depiction of Frank Hawden, read Ada Cambridge’s short story, A Sweet Day. According to the family, both Harry and Frank are suitable husbands for Sybylla. Develop a Venn diagram to outline how each suitor is represented and how this representation allows us to align our preferences with Sybylla’s. This can be done equally well with the novel or the film.

In pairs find points for and against the statement: The characterisation of Sybylla’s suitors is an expression of nationalism.

The film

Film trailers

Students can look at these two trailers of the film for discussion.

Trailer 1 : My Brilliant Career

- What is this trailer saying about the way the film was received? What aspects of the film created positive reaction?

Trailer 2 : My Brilliant Career

Divide class in two, focusing on different aspects: one can look at visuals, the other can copy the quotations that are used. They can share their findings to these questions.

- What does this trailer open with?

- Follow the sequence of shots – what oppositions do the shots set up?

- What ideas are being reinforced by the selected quotations?

- Is there any other quotation that you think has been left out?

Evaluation

How effective is each trailer in summing up the themes of the novel?

Adaptation of the novel

The 1979 film adaptation of My Brilliant Career (accessible with a ClickView subscription) remains very close to the text. Some parts of the novel were excised (Sybylla’s early life), and some characters (Uncle Jay Jay and Everard Grey) as well as some scenes (the horse-races on the Wyambeet, the ball at Yabtree and the muster at Cummabella) have been merged. The incident when Aunt Helen counsels Sybylla not to lead Harry on: ‘”I have known him all his life, and understand him, and feel sure he loves you truly. Tell me plainly, do you intend to accept him?” “Intend to accept him!” I echoed. “I haven’t once thought of such a possibility. I never mean to marry anyone.” “Don’t you care for Harold? Just a little? Think.”‘ has been changed to a scene in the film where she tries to make Sybylla understand that Harry would not marry someone like her.

Compare beginnings and endings.

- Look at the opening of the film and reread the first chapter.

- Look at the ending and re-read the last chapter.

Consider any differences in the two texts and justify the director Gillian Armstrong’s decision. Work in groups to suggest alternative openings or endings.

Other scenes have been added such as:

- the pillow fight

- the aviary with Aunt Augusta

- Sybylla’s line at Harold’s second proposal ‘I’m so near loving you’.

Have students consider these changes and suggest what has been achieved by them in the interests of a film audience’s engagement (not to mention cost reduction!) and audience approval.

Interpretation of character

Judy Davis’s interpretation of Sybylla Melvyn captures that time of a girl’s life when she is caught between childhood and adulthood. She is coquettish and flirtatious with Frank Hawden and Harold Beecham without realising the effect that she is having on them and being dismissive or horrified when they interpret her behaviour as more experienced men would. Judy Davis is considerably older than Sybylla is in the novel.

Student activity:

- Choose a teenage actress and imagine her playing the part of Sybylla in key scenes in the film. To what extent would this change our attitude to her, to her ambitions and to her romantic involvements? (Remember that at the end of the 19th century girls often married in their teens).

- Choose one scene for close analysis and, if possible, use screen shots as illustrations of your argument to answer the question: How does Judy Davis achieve the sense of a young girl wavering between childhood and womanhood in her appearance and her acting?

Exposition of themes

The film brings out the themes of the novel in many ways and one productive way of demonstrating this is through examples of paralleled or contrasting screen shots. Collect screen shots of the following scenes.

- The dust and drought at Possum Gully and the lush green gardens of Caddagat.

- Sybylla sitting in her room at Caddagat and the cut away to her mother sewing in Possum Gully.

- The broad external shots of the bush and the interiors of Caddagat or Five Bob Downs.

- The ball at Five Bob and the barn dance.

Student activity:

In groups study one of the pairs of screen shots side by side and:

- outline each scene and place it in the context of the narrative

- analyse the scenes visually (colour, vectors, salience etc)

- comment on the effects of the mise-en-scene.

Post your findings on the class intranet.

The film, feminism and context

Consider the context of the making of the film: it was made during the second wave of feminism. At this time, much intellectual effort was expended on identifying women’s writing from the past. Publishers such as Virago Press in England were re-discovering the writing of women that had been lost. In Australia there was an upsurge of scholarship into the writing of 19th century women, showing just how important their work was and also offering an alternative reading of life in that century.

- Why would Gillian Armstrong be making such a film at this time?

- How might the audience of 1979 have rethought feminism in the light of this film?

A critical reading

One of the most important aspects of creation of a text is the selection of material. This is particularly so in adapting a long, detailed and at times rambling novel to the much tighter artistic form of the film. In this case Gillian Armstrong has placed considerable emphasis on Sybylla’s egotism which is, compared to the book, relatively much more prominent. The final scene of the film, where Sybylla is shown silhouetted against a bright orange sunset, with her arms outstretched over a wooden cross beam could be seen as a hint at crucifixion.

(ACELR039) (ACELR040) (ACELR042) (ACELR044) (ACELR050)

Rich assessment task 1: Essay

My Brilliant Career is about the will for self-realisation and the tenacity in achieving it. For Sybylla this involves desires incompatible with expectations and loyalties. How well does Miles Franklin succeed in representing this struggle through the novel form? Support your point of view with illustrations from the text.

(ACELR042) (ACELR043) (ACELR045) (ACELR046)

Rich assessment task 2: Critical/creative project

Adaptations of classic texts has been a popular exercise among writers and film makers. The most extensively plundered novelist has been Jane Austen. Pride and Prejudice has been made into films, television series and countless games. It has undergone many more radical new lives as: Bridget Jones Diary, Lost in Austen, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, not to mention prequels and sequels. The best of these provide insights about the societies in which they were written or the nature of artistic endeavour.

Students are to create an adaptation of the novel My Brilliant Career. They may work with a change in period, setting, culture, genre, character or point of view. They can work with any form: narrative, poetry, drama, graphic story, web site, mashup. Their adaptation must reconsider aspects of the novel for our own time and culture.

Their adaptation must be accompanied by:

- an explanation of why this interpretation has been chosen and how it casts a new light on the novel and ourselves

- a reflection on the personal difficulties and pleasures of adaptation.

(ACELR048) (ACELR049) (ACELR051) (ACELR052)

(5 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(5 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)