Introductory activities

Bruce Dawe

But poets are naturally suspect;

they are the shower without the bath mat, the rug on the slippery

parquet floor . . .

‘Interviewing a poet’, Sometimes Gladness, p. 270

Participating imaginatively: Exploring student attitudes to poetry

Ask students: Which of these forms do you prefer to read on a scale of 1-5?

|

1

Love it

|

2

Don’t mind it

|

3

Indifferent

|

4

Don’t like it

|

5

Hate it

|

|

| Movies | |||||

| Documentaries | |||||

| Poetry | |||||

| Novels | |||||

| Magazines | |||||

| Newspapers | |||||

| Comics or graphic novels |

After students complete their surveys, collect these and assign a student to collate the results and read them to the class. They can add up the marks using the 1-5 scale – the text with the least numbers is the most popular. Most likely they will find that poetry is the least popular, so find out why. Divide the class into six small groups. Assign a de Bono’s hat to each group – they have to respond only according to their hat. After a few minutes reorganise the groups so that there is a student representing each hat in the newly formed group. They have to go around the group and present what brainstorming was produced by their original hat groups.

- White hat: list facts or information about poetry.

- Red hat: list feelings about poetry and in poetry.

- Yellow hat: outline the positive side to poetry.

- Black hat: outline the problems created by poetry.

- Green hat: what are the creative possibilities presented by poetry?

- Blue hat: organise a plan for understanding poetry.

Now open the discussion around the room:

- Why would any Australian write poetry knowing that it was mostly ignored?

Reading

Students can read the poem ‘Interviewing a Poet’ on page 270 and pages xvii-xxi of the introduction to Sometimes Gladness.

Writing

Students can use this poem and ideas from the introduction and lesson to write a reflection about the role of poetry and poets in society. Alternatively, they could write and present a poem called:

If I were a poet I would write

Research

Students should conduct research on Bruce Dawe

- When did he live?

- What was his childhood like?

Personal response on reading the text

The initial reading

The best way to introduce the poetry of any poet is to read lots of poems aloud so that the rhythms and ideas become known. Students can open at any page of the book and read aloud to the class. It is a good idea to commence any such reading with good readers or even with a teacher first, so that the standard is established. Suggestions 2 and 3 are ways of further developing this reading aloud process.

1. Understanding the title of the collection: Sometimes Gladness

Ask students to discuss in groups:

- What does the title Sometimes Gladness convey about life?

- If you had to write about the moments of gladness in your life, which moments would you pick?

- Look at the poem that acts as an epigraph (page xv)

- Read the first line of each stanza: What relationship does each first line evoke?

- Which relationships would you write about?

2. Performance

Dawe’s poetry captures such strong voices that it is worth presenting as performance. A wonderful poem for performance is ‘Enter without so much as knocking’ but others can be found in the index of dramatic monologues. Hand different poems to groups and ask students to dramatise them without knowing the poet or the poems. Present the poems to the class and enjoy the voices that can be created. What image of Australian life does each poem capture and how effective is Dawe’s choice of language in doing this?

3. Reading poems

Divide the class into groups ands assign a poem to each group. They practise a reading of the poem to present to the class. Students listen and can use the Y chart to gather ideas about the poem after the reading. The Y chart can refer to how they feel, what they imagine it looks like and what sounds they hear.

Outline of key elements of the text

Possibilities for teaching

Sometimes Gladness has been organised to facilitate different ways of teaching.

Chronological organisation of poems leads to:

- a contextual study of the issues that concerned Australians at each period

- a study of the author’s development as a poet over time

- what issues the poet engaged with at different periods.

Index of themes

Comparative study of groups of poems on similar ideas considering whether:

- the poet’s attitude to an issue remains stable throughout the different poems

- there is a clearly identifiable stance

- there are patterns of language that can be discerned, linking the poems.

Index of forms

A study of different forms of poetry, to consider:

- how the choice of form affects the poem’s meaning

- how changing the poem to a different form would affect meaning

- how other poets use this form

- which form Dawe favours and why.

Synthesising task/activity

Having read and heard at least three of Dawe’s poems, student should write their own ‘Sometimes Gladness’ poem of the experiences, people, or places that have affected them.

Work in pairs to critique each other’s work and offer some editorial advice on: structure, images, line length, rhythm, sounds, punctuation.

Reflect on the experience of the rewriting – how important is it to have an editor for your work?

AC: English

Year 9: (ACELA1553) (ACELA1561) (EN5-2A) (EN5-1A)

Year 10: (ACELA1569) (ACELT1815) (EN5-3B)

AC: Literature

Unit 1: (ACELR005) (ACELR009) (ACELR010) (ACELR013) (ACELR014)

Unit 3: (ACELR038) (ACELR044) (ACELR048) (ACELR049)

The writer’s craft

A poem sounds itself into speech into words and the symbolic record of that progress lies on the page before us.

Introduction, Sometimes Gladness, p. xix

Bruce Dawe’s skill lies in being able to articulate the complex issues of everyday Australian life using accessible language and imagery. His themes are therefore centred on everyday issues that affect everyday people. He is also a poet with a strong social conscience and this is evident in the way he takes topical issues such as unemployment and develops a sensitive perspective.

Dawe’s themes include:

The index of themes (pp. 323-27) suggests some ways that the poems can be studied under themes, but these themes are not exhaustive.

Poetic forms

Dawe favours free verse but he also uses rhymed forms and for some poems he employs the sonnet form. Free verse allows for the development of an idea in a free form that appeals to the modern audience in being more prose-like. Dawe’s forte can be seen in the strong characterisation emerging in the number of dramatic monologues that address the reader on controversial issues such as hanging or nuclear war.

He also includes narrative poems. A poem such as ‘At Shagger’s Funeral’ captures the tone of Paterson’s bush ballads with a touch of humour for Shagger, with ‘the old shag-wagon’ ‘caught with his britches down’ at the end.

Look at the index (pp 328-332) for the list of different forms but be aware that this does not include forms such as narrative.

Text and meaning

Close study of a theme: the War Poems – a comparison Year 9 activity:

Interpret, analyse and evaluate how different perspectives of issues, events, situations, individuals or groups are constructed to serve specific purposes in texts.

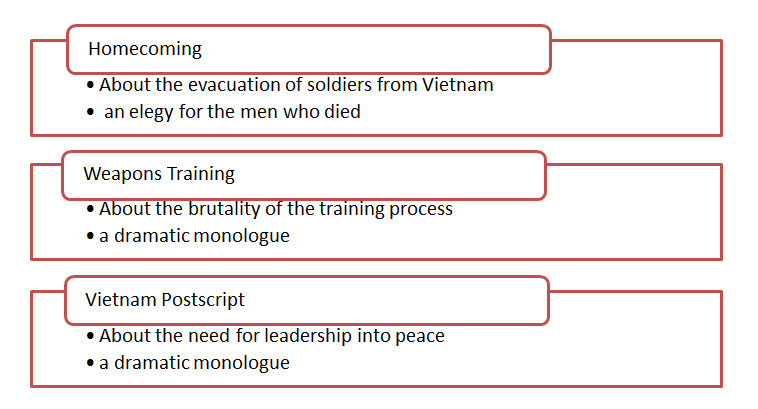

Poems to use for this activity are: ‘Homecoming’, ‘Weapons Training’, ‘Vietnam Postscript, 1975’.

In an interview in 1997, Bruce Dawe spoke with Robin Hughes and said this about the Vietnam War: ‘But it [the Vietnam War] was all a nonsense, and a very tragic one, to me, and I wrote out of that sense of the tragedy of it’. Watch this interview extract of Dawe talking about his war poems (the transcript is also available).

Dawe was in the RAAF but his only war experience overseas was a posting to Malaysia. Therefore, his poems about war might draw from some experience but they are more about Dawe, the man with the social conscience, speaking out against what he perceived to be a useless war.

These three poems have very different approaches to the same war. Students can complete this close activity with examples.

‘Homecoming’ (1968)

‘Homecoming’ is written in the third person. A significant feature of the poem is the use of present continuous tense (ending in –ing) and repeated phrases to indicate ongoing and extended activity. The opening is filled with lists of actions (…………………………. ), descriptions of transport (…………………………) and types of soldiers identified by their hair (………………………………..). Commas are used to divide the extended lists and create the sense of the pace of the action, while dashes stop the reading for a new action. The scale of the official evacuation is impersonal compared to the ‘noble jets’ bringing them home (‘with ………………………..’). The longing to come home is focused in the repletion of (………………………). The landscapes that the plane flies over are (……………………..). In the final lines an elegiac sense of mourning enters and spreads as the (………………………………………………………….). The paradox of a homecoming for those who are dead is expressed in the final line (……………………………………………………).

- Listen to a reading of ‘Homecoming‘ after studying the poem. Does this reading capture the feelings you sense in the poem? Explain your attitude.

- Watch this student video of the poem and assess its merits against another video.

- Use the format of the ‘Homecoming’ discussion above to create a paragraph on each of the other poems: ‘Weapons Training’ and ‘Vietnam Postscript, 1975’.

‘Weapons Training’

Students can consider these comments by Dawe (2008) when exploring this poem: ‘In ‘Weapons Training‘ the metaphors used are from the common stock of such language which has its equivalents wherever military training is needed. (Written later, during the Vietnam War, the racist references were obligatory.) As the focus for this process of stripping-down and re-assembling for recruits, I chose the machine-gun drill then in use. It is the weapons instructor who is speaking to a squad of new recruits.’

- Find examples of the metaphors ‘from the common stock of such language which has its equivalents wherever military training is needed’

- Why is this poem so shocking?

- How does the poet capture the sound of ‘machine gun drill’

- What is Dawe saying about war?

Students can use these openings to write about ‘Vietnam Postscript, 1975’ or other war poems.

- ‘Vietnam Postscript. 1975’ is written in ………………….

- A significant feature of the poem is …………………

- The opening is ……………………

- (Punctuation – name the punctuation or lack of) is used to ………………….

- The (discuss any extended idea) ……………………

- In the final lines ………………………………………………..

Once each poem has been considered individually, they can be compared in a table like the one below:

| Poem | Subject matter | Theme | Style (language) | Effect |

| ‘Homecoming’ | ||||

| ‘Weapons Training’ | ||||

| ‘Vietnam Postscript, 1975’ |

Close study of form: dramatic monologue

‘More often I tend to work at an issue through a particular character who’s identified negatively or positively with a particular issue.’ Bruce Bennett and Brian Dibble, 1979, ‘An interview with Bruce Dawe’ in Westerly.

Form

A dramatic monologue is a piece of writing capturing one person’s voice and directly addressing the reader. It has dramatic elements in being able to be performed.

‘A Victorian Hangman Tells his Love’

One of the most powerful dramatic monologues in the book is the poem ‘A Victorian Hangman Tells his Love’ (p. 79). The poem can also be studied thematically alongside ‘On the Death of Ronald Ryan’ (p.80) and ‘The sting’ (p. 81).

Ask a student who also studies drama to present this to the class as a reading – give some practise time first.

The event: Context

It is imperative to teach the context of this poem:

- The Australian Coalition Against the Death Penalty (ACADP) have a website on Ronald Ryan

- The Herald Sun True Crime Scene article on Ryan will also capture the imagination of students using crime photos as support.

Ask students:

- Why is this event so interesting or important? What issues does it raise?

Title

Victorian = Victorian period when gaols were being revolutionised

Victoria = the state where the last hanging took place.

hangman linked with love – explain the paradox.

Voice and tone

As with all dramatic monologues, the voice of the speaker is important in creating a sense of the character of the person. Voice in writing is developed through choice and organisation of words. The only clues we have are through what this person chooses to say and how he says it, starting with the opening line:

Dear one, forgive my appearing before you like this

Ask students:

- Which of the following words best describes the tone of the first line and the whole poem. Why?

- informative, old fashioned, casual, formal, unexpected, official, gentle, respectful, insolent, ambiguous, offhand, callous, misanthropic, sympathetic, empathetic, conspiratorial, angry

- Who is he addressing?

- One of the limitations of dramatic monologue is that we cannot hear other voices. How does this poem allow us to witness the other character?

- What kind of person do you think this hangman is?

The voice is instrumental in creating a mood. How would you describe the mood of this poem and how it makes you feel?

Structure

Ask students to note the interplay of first person and second person pronouns. It may be useful to set up a table such as the one below to show the movement between the two characters. Don’t give all the answers but ask students to collect these.

Ask students:

- What insight do we gain about the way the poem is structured?

- Consider the process of the hanging and how each part of the poem reflects the process.

| First person | Second person | The process of the hanging |

| I would have comeIf I must bind your armsI would dispense withI know your heart isI trust | You have dreamed about this moment of consummationIf you have anything to sayYou did not reject | Preparing for the hanging |

| Let us now walk a stepWe’re wed | The hanging | |

| I slip itAllow me to adjustI, alas, am not yet fit to share | You have been given a clean bill of healthYou will go forthYou will sinkAccept your roleYou are this evening’s headlines. | The report after the hanging |

Time and verbs

Another way of understanding the movement of the poem is to look at the verbs. This poem moves between the actions taking place (present tense), the events that follow (future tense) and possibilities (modal verbs).

Students can highlight all the verb groups (this includes any auxiliary/modal), remembering that verbs are usually more than one word except in simple tenses such as simple present, which is also used here.

Students should consider:

- Why does this poem favour the present simple tense?

- When is passive voice used and who is it applied to? Consider why.

- What future is suggested by the poem?

Metaphors and similes

This poem depends on the sustained metaphor of a marriage that begins from the title in the word ‘love’.

Students should trace all the references to the ritual of a wedding on the table below – relating them to the hanging ritual. These can include the phrasing and any similes that also relate to the wedding.

They should explain the effect of this unexpected metaphor.

| Wedding | Hanging |

What other metaphors and similes can students find and what is their effect?

Punctuation and line length

Bruce Dawe does not have one style of punctuation for all his poems. Some poems follow the formal convention of starting each line with a capital but this poem does not. Instead it uses enjambment as the lines move fluidly through the hangman’s speech. Students should consider: Why would this poem about a formal event like a hanging ignore the formality of punctuation? What attitude to the hanging would this convey?

Other punctuation features are the use of ellipsis marks and dashes. Students should note where these occur and give an explanation about the effect.

The other feature is line length. Line length is an important visual cue to something that stands out – this can be as simple as creating a visual effect of movement or it can contrast with something else in the poem.

Three lines stand out because they are relatively shorter than the others and students should consider why this is so.

I would have come

. . .

modern bride.

With this spring of mine

Evaluate the poem

The following is an extract from an interview with Bruce Dawe in which he talks about the poem ‘The Victorian Hangman Tells his Love’.

DAWE: . . . And even in the hangman poem, if one takes it slowly, it couldn’t be said that I was really attacking the hangman, but was seeing him as a victim of the State policy just as much as the more obvious victim, the person being hanged.

BENNETT: In that case you seem to be particularly interested in the language of deception, of bureaucracy and of State officialdom. You seem to be enjoying, in the process, the language that you’re satirizing. Is that right?

DAWE: Yes, I think so. In that one in particular I think I had in mind the way in which even those who are bureaucratic (and the word isn’t necessarily a derogatory word, though it’s often used that way) themselves may only be the expressions of bureaucracy. The people typified may be themselves caught in something much larger than they can handle. They themselves don’t know the answer to the problem but are merely acting out certain roles as in fact a hangman is. One is not really indicting the hangman per se at all. One is indicting a general philosophy. That may be why the bureaucracy is merely the instrument of putting into effect that philosophy.

More recently in 2008 Dawe said: ‘The hangman’s apologetic speech in this monologue (echoing Miles Malleson’s warden in Kind Hearts and Coronets) I also based loosely on the Elizabethan courtly love tradition – hence the title, ‘Victoria Hangman tells his love’. In this convention, the frustrated lover is usually dying of unrequited love, and is embarrassed by his situation. In this poem there is a marriage (a matter of life and death), an altar (the scaffold), a public context with the public in ritual attendance, and a lover (the hangman) shamed by his situation.’

Students can write an extended response using this extract and answering:

- How effectively did Dawe achieve his purpose in this poem?

(Extra reading on the poem: John M. Wright, ‘Bruce Dawe’s poetry’, Westerly, 1974.)

(ACELY1742) (ACELT1643) (ACELR042) (ACELR043) (ACELR049) (EN5-2A) (EN5-3B)

Synthesising task/activity

Following a theme

1. Analytical: Read the other war poems listed in the index (p. 324) and select 2-3 to discuss. Write a comparative essay on Dawe’s war poems. Develop your own thesis to argue. An example of a comparative essay on war can be found on the internet.

2. Imaginative: Work in groups to create a new poem. Each student can take one poem from the list on page 324 and find one line they like best. These lines are presented to the groups. Each group then forms a new poem using these lines. They may have to add their own lines in between to make the new poem work. Present this to the class.

(ACELY1742) (ACELR011) (ACELR014) (ACELR045) (EN5-2A)

The dramatic monologue

1. Composing and performing

Students should read the newspapers to locate an event that interests them. They can then consider the features of a dramatic monologue as described by Bruce Dawe in the Judith Wright lecture to the Poets Union in 2008: ‘The dramatic monologue as a form can appeal to us for a number of obvious reasons. Firstly, it is direct speech; it cuts out the middle-man, the go-between. The distancing conventions are abolished . . . A second advantage from the point of view of the author is that, if successful, such dramatic monologues pay a compliment to the reader/audience. The author says: Here they are, they are yours; make of them what you will . . .

A third advantage the dramatic monologue may have for writers is that it can solve one of the major problems we face: how to be aesthetically objective when our feelings are so strongly engaged as to make it unlikely . . . the impetus of speech-patterns as they develop in a dramatic monologue are of central importance. Lose the rhythm, and you’ve lost the thread through the maze of the experience.’

With these comments on the form in mind, students can then compose their own dramatic monologue on an issue they have located in the news which they perform to the class.

In preparation for writing the monologue students will need to:

- choose a speaker who would provide an interesting perspective on the event or issue

- consider the character of that speaker

- decide how they will communicate his/her/its voice and attitude.

2. Composing an analytical piece of writing

Students can use the close study above as a model and conduct their own studies of another of Dawe’s monologues listed on page 330. They can either:

a. Write a critical essay on their own choice of dramatic monologue, developing a thesis that they can argue, OR

b. Write a comparative study of two dramatic monologues discussing the way Dawe uses dramatic monologue form to reflect on important social issues.

(ACELT1643) (ACELT1815) (ACELR014) (ACELR050) (EN5-3B)

Comparison with other texts

In order to gain a fuller picture of Australian poetry and Bruce Dawe’s place in poetry, students should be encouraged to read some more poets who are contemporaries of Dawe. The Australian Poetry Library provides a comprehensive source of poems by pre-eminent Australian writers.

Evaluation of the text as representative of Australian culture

‘[Bruce Dawe] our foremost living example of the popular poet’ – Chris Wallace Crabbe, 1979 (Dennis Haskell, 1997).

The influence of Bruce Dawe on generations of students cannot be underestimated. He has often been selected on school senior English curricula because he is so quintessentially Australian, speaking about issues that appeal to Australians while presenting a social conscience in accessible language. His work has been studied under topics such as consumerism, identity, belonging and as an example of Australian literature. He has even been called an Australian literary icon by MP Kelvin Thomson.

The Bruce Dawe Poetry Prize, judged by the University of Southern Queensland where Dawe was professor, is one way that Dawe has supported future Australian poets.

Dawe is therefore a pre-eminent Australian writer who:

- writes about Australian issues

- is taught and known widely in Australia

- captures the Australian voice.

Over his career Dawe has found himself and his poetry written about in many articles, sometimes in praise and sometimes more critically. Most of the criticism centres on his popularity in reaching the everyday person. Dennis Haskell’s article ‘Bruce Dawe, the Ordinary and Extraordinary Bloke’, published in Southerly in 1997 is a good place to see the different perspectives.

Some of the attitudes that Haskell cites are:

- that poet of Middle Australia who does not mind the tag’ – Helen Frizell, Sydney Morning Herald, 22 November 1980

- [looking] more like a salesman than a poet . . . [Dawe] seems the very opposite of artistic’ – Terry O’Connor, Newcastle Herald, 20 November 1991

- [many of Dawe’s poems] reach a public who, otherwise, would not read a poem from one year’s end to the next.’ – Kevin Hart, 1979 (in Haskell)

Activity

Students should become aware of the issues surrounding Dawe as a poet by reading Haskell’s article. They can locate the comments and list these in a table as below:

| Comment | Source | Negative | Positive |

They can also consider other reviews researched by them from a variety of web sources. They can then discuss:

- How do we measure the worth of a poet?

- Why has Dawe attracted so much controversy?

Identifying and justifying language/stylistic techniques for specific narrative or dramatic purposes

Australian elements for study:

- humour

- the suburbs and Australian places

- Australian issues

- Australian speech patterns

Australian humour

Australian humour is regarded as so important culturally that the Australian Government website writes this:

Australian humour has a long history that can be traced back to our origins as convict colonies. It is therefore no surprise that a national sense of humour quickly developed that responded to those conditions. This unique sense of humour is recognised (although maybe not always understood) the world over as being distinctly Australian. Our humour is dry, full of extremes, anti-authoritarian, self-mocking and ironic.

Explore the following Dawe poems with this definition of Australian humour in mind.

In the following extracts:

- explain how the humour works in each of these extracts

- is there anything distinctively Australian about the humour?

‘The Not-so good Earth’, p. 72

For a while there we had 25-inch Chinese peasant families

famishing in comfort on the 25-inch screen

and even Uncle Billy whose eyesight is going fast

by hunching up real close to the convex glass

could just about make them out –

‘Which One’s the Dog?’, p. 88

Which one’s the dog? you find yourself saying

after the last escape-route has been cut

with the photograph-album lying heavily . . .

‘At Shagger’s Funeral’, p. 109

At Shagger’s funeral

there wasn’t much to say

. . .

The service closed with a prayer, and silence beat

Like a tongue in a closed mouth.

Of all the girls he’d loved or knocked or both,

Only Bev Whitside showed – out in the street

She gripped her handbag, said ‘This is as far

As I’m going, boys or any girl will go,

From now on.’

‘Head for the Hills’, p. 59

‘Head for the Hills!’ and before you could say, ‘Whose shout!’

The pubs were empty, sentences hung in mid-air . . .

Then in groups:

- find other examples from these poems or Bruce Dawe’s poetry in general of humour that appeal to you

- decide which you think are particularly Australian or particularly funny.

Share these with the class.

Australian places

What features of Australian places does Dawe capture in these extracts? (Note: ‘Provincial City’ is about Toowoomba where Dawe lived most of his adult life.)

‘Cravensville’, p. 123

‘Run of the mill’, you might well call this town

– A place where many go, but few remain

‘Provincial City’, pp. 138-9

Climbing the range your ears pop like champagne

. . . In season the currawongs in the camphor-laurels

cry like tin-shears.

(The jacarandas hang their sheets

of blue water in mid-air.)

Australian issues and speech patterns

Students can work in groups on selected poems, to list the issues in the poems and to locate examples of Australian speech.

(ACELY1752) (ACELR037) (ACELR038) (ACELR039) (ACELR040) (EN5-8D)

Rich assessment task 1: Design a webpage

In this group task, students will design a webpage called ‘Dawe: an Australian poet’, drawing on the poems in Sometimes Gladness. Teachers can access templates for web design pages on the weebly education site.

The task is to design a webpage that will attract students to read Dawe’s poetry. The best way to do this is to find ‘grabs’ (good lines) from a few poems and use strong visual appeal. Students could include links to poems, interviews, videos, but don’t forget that they need to show poetic techniques.

Students need to consider: layout, numbers of columns, top bar/ribbon information, a logo design, the text size, the colour, icons.

All webpages have to be presented to the whole class with an explanation of the decisions that were made. A voting system can take place to decide which webpage was the best in capturing what poetry is about. These pages can be uploaded on the school server.

(ACELY1748) (ACELY1776) (EN5-2A)

Synthesising core ideas

The poet as private and public person

Dawe has been acclaimed by his peers including important Australian poet, Les Murray, who has described him as ‘our great master of applied poetry’. The term ‘applied poetry’ is an important one suggesting the ability of this poetry to connect with all people who can apply the poems to their own lives. We started this unit with an exploration of the way that poetry disengages the regular public by looking at student perceptions about poetry. That is why a poet like Bruce Dawe is so important. He acknowledges and respects his audience’s right to connect.

Dawe realises: ‘Each of us is both a private person and a public person, an ‘I’ and a ‘we’, with a private fate and public fate . . . [Poetry] helps us to see ourselves and our work more clearly. If confused, it will help us to see our confusion for what it is. If we are lonely, it will help us to recognise that we are not alone in our loneliness.’ (Introduction,Sometimes Gladness, pp. xx-xxi)

Rich assessment task 2: nominating Bruce Dawe for an Order of Australia

Ask students to write the nomination for Bruce Dawe to receive The Order of Australia and deliver the speech awarding the OA to him.

Bruce Dawe has received the Order of Australia. Before such an award is given there has to be a nomination process. Once decided, the Award also has to be given at a ceremony where the awardee is introduced in a way that shows why the Award was given.

Students can watch this video of MP Kelvin Thomson (2009) talking about ‘Australia’s Literary Icon: Bruce Dawe’. He talks about the importance of Dawe’s poetry in his life, recites a poem and explains why it had an impact. This can be used as a model but students should be encouraged to be even more creative in their presentation.

They then:

- Find the Order of Australia nomination form and look closely at what is valued. They are to complete the nomination for Bruce Dawe to receive an award. This begins in Section 3 of the award nomination page. Students need to think carefully about everything he has done and how he represents Australia in his work. They should give evidence of his engagement with public life through poems on important issues.

- When an award is given the person has to be introduced and the award has to be justified. Students write and present the speech at the ceremony offering the award to Bruce Dawe. To make the speech lively, entertaining and moving, they should make reference to aspects of particular poems and offer a reading.

(ACELY1752) (ACELR037) (ACELR038) (ACELR039) (ACELR040) (EN5-8D)

(1 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(1 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)