NOTE: It is not anticipated that students will complete every activity in this unit. In designing a program, teachers should select activities that best suit the context of their students.

Introductory activities

Introducing the concept of identity

Have students collate their own mini-gallery of artefacts that represent their identity. They could bring in several objects and documents that connect to important experiences, personality traits or relationships. Rearrange the classroom so that each student has a desk and wall space upon which to display their collection. Students could browse each others’ collections and then, choosing one, try to work out the story behind the collection. Have a ‘show-and-tell’ lesson where students explain their collections. Lead into a class discussion of adolescence as a period of identity formation, as teenagers push boundaries and test out ‘versions’ of themselves, and the influences upon their personal shift from their parents as primary source to media and their peers.

Introducing the genre

Read and discuss:

- the interior nature of these sorts of texts – the reader is usually given significant insight into the main character in some ways

- the implications of multiple perspectives and/or points of view

- the sense of verisimilitude that is created by a collection of ‘found’ items, especially those that appear to be ‘official’ or published documents

Discuss whether social networking sites can be considered a multimodal form of the epistolary genre: does the combination of messages, status updates, embedded texts such as YouTube videos, articles and photographs, etc. on such pages combine to form a kind of narrative?

Introducing the text

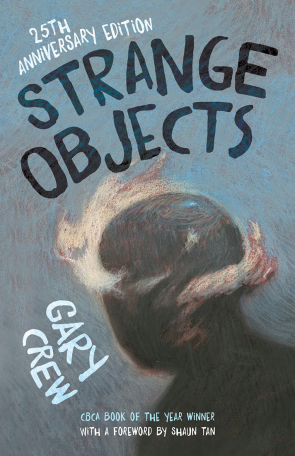

Examine the cover. Explore the font and imagery used on the cover of the edition students are using, considering the connotations suggested by these design features. See here for an example (PDF, 173KB).

Think about the epigraph. Consider the H. P. Lovecraft quote used as the epigraph. Use the ‘think-pair-share‘ strategy to explore the possible meanings of this quote and the way it might position readers. Explain the use of ellipsis at the end of the quote, which further adds to a sense of foreboding, as does Lovecraft’s reputation as a horror writer. Introduce the concept of intertextuality and its implications for reading the remainder of the novel.

Read through the Prologue, ‘Notes on the Disappearance of Steven Messenger, Aged 16 Years’, as a class. Discuss student responses to this Prologue. You may wish to consider the following prompts:

- Why might Steven be missing?

- Why might Steven be charged with a crime under the Historic Shipwrecks Act?

- Is the threat of possible criminal charges enough reason for him to have run away?

- How do you think Steven might have felt discovering the pot and mummified hand? How would you feel?

- Who has supposedly written this Prologue? What is her job? Does this person seem like a credible narrator? Why might Crew have opened the novel with a prologue from such a person?

- How do you feel about the novel so far? Does this opening intrigue you and make you want to read on?

Introducing context

Research the history of the Batavia and its wrecking on the Abrolhos reef. The following websites may be useful:

- National Museum of Australia – Wreck of the Batavia

- Australian National Maritime Museum – The Batavia shipwreck disaster

- Western Australian Museum – Batavia, 1629

- Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water – National Heritage Places – Batavia Shipwreck Site and Survivor Camps Area 1629 – Houtman Abrolhos

Using Popplet, Pinterest or a similar application, create a digital pinboard that includes various documents, maps, videos and so forth, exploring this event. This could be completed as a small group or whole class activity, or individually for stronger students. Alternatively, use a retrieval chart such as a 5W chart to record salient facts.

Locate Texel, in the Netherlands, as well as the Abrolhos reef and islands, on a world map. Chart the journey of the Batavia from the Netherlands to Western Australia. Some students may like to experiment with charting their map online using the Travellerspoint website, which allows them to add notes and pictures at each stage of the journey.

Additional activities

Conduct a timed creative free-writing lesson. Bring in an object or small collection of objects and ask students to create a narrative that incorporates each of them in a meaningful way. Use this as an opportunity to introduce narrative elements such as character, setting, plot and so on. You may wish to set limits such as keeping it to a 50-word micro-story. Many examples of micro-stories can be found on the internet.

Initial understanding and response

Questions and comments while reading the text

Provide each student with several sticky notes. Generic, non-brand versions of these can be purchased quite cheaply from discount stores and office supply stores. Students can use these as they read to indicate sections of the text they wish to comment on, whether this be:

- a question they wish to ask

- a striking use of language they wish to share

- an ‘aha!’ moment (particularly if they think they have discovered a thematic idea)

- an emotional response

- a prediction they are making

Encourage students to annotate their sticky notes so that they remember why they have marked this particular point in the novel. Twice a week, as students are reading the novel, allow time for pair, small group or whole class discussion to share these ideas. You may wish to change the focus for each discussion; for example, one time only look at striking uses of language and another time, predictions and so on. This will encourage the students to maintain close reading and to have aspects of their reading validated. This is also a useful tool to check if students are keeping up with set reading goals!

Personal connections with own experience: identification with characters and situations

Steven’s character is quite ‘human’ in the breadth of emotions he feels. At times he experiences loneliness, warmth, disgust, isolation, anger, frustration, spite, depression, curiosity and so on. Use cut-outs of a human figure, roughly A4 in size; a template is available (PDF, 408KB). At the top, write one of these (or other) emotions. On one side, students should identify an example in the text where Steven experiences this feeling. Encourage the inclusion of quotes to support the example. On the reverse, they could write about a time when they experienced a similar emotion or situation. Use these to lead into a discussion about empathy and whether Steven is an empathetic character. For example, in Item 11, Steven feels let down by his friend, Kratz. Was there a time when the student felt let down?

Initial reflection on completion of the text

Students could create their own quizzes to test each other on their factual recall of the text. Encourage students to design a mixture of multiple choice, true/false, close and short answer questions, focusing on significant aspects of the text. They should also write the answer key to help develop their own understanding. Working within pairs or small groups, students will then swap and complete each others’ quizzes. Alternatively, a sample quiz is also available (PDF, 75KB). Focusing on factual recall, this quiz is designed only to assess whether students have completed reading the text.

Conduct a poll to find out who enjoyed the epistolary nature of the text or who found the multiple voices and lack of linearity confusing.

Additional activities

- Set a journaling activity, where students imagine themselves living Steven’s rather isolated lifestyle, with the issues he faces with loneliness, grief and so forth. Sensitivity would be needed here as the text deals with issues such as depression and the loss of a parent.

- Students might like to write a letter to Gary Crew to share their thoughts on the text and ask any questions they might have.

Outline of key elements of the text

Plot

The novel is ostensibly a collection of records collated by the protagonist, Steven Messenger, into a scrapbook, which is then subsequently published by another character, Dr Hope Michaels, who adds a Foreword and Afterword. The records range from newspaper clippings, letters, journal entries from Steven himself, the serialised journal of Wouter Loos (a marooned sailor from the Batavia shipwreck) and a cassette tape transcript.

Although fragmented, there are three basic narrative streams. Steven recounts his own, albeit unreliable, experiences after he discovers the ‘strange objects’ of the title: an iron pot, a mummified hand and a gold ring. Although the pot and hand are turned over to the authorities, Steven keeps the ring. Wearing it, he starts to have visions of the past and other disturbing visions involving an alternate version of himself and alien spacecraft.

The second major narrative stream is the serialised journal of Wouter Loos, which recounts the story of his survival on mainland Australia, along with another survivor, Jan Pelgrom. They encounter the local Aboriginal people and are taken in, meeting another survivor of a different shipwreck. Jan becomes increasingly disturbed, and after taking Ela, the European girl, as a wife, ends up killing her. They also bring disease to the Aboriginal people.

The third stream is that of Dr Hope Michaels, who charts the investigation into the artefacts and reveals Steven’s strange disappearance.

Ultimately, the novel resists any attempt at resolution. The reader does not find out what happens to any of the major characters and is left with an array of questions.

Characters

| Steven Messenger | The isolated teenaged protagonist who discovers the artefacts and, after keeping the ring, becomes increasingly erratic and experiences visions. |

| Nigel Kratzman | Steven’s neighbour and somewhat friend. |

| Wouter Loos | A real historical figure, Wouter (and Jan Pelgrom) were cast away for their roles in the mutiny and murders that took place on the Abrolhos Islands after the shipwreck of the Dutch East Indiaman Batavia; while there is no evidence Loos made it to the mainland, Crew has speculated on what may have happened if he had. |

| Jan Pelgrom | Loos’ 16-year-old fellow castaway and original carrier of the ring, who becomes increasingly disturbed throughout the course of the novel. |

| Charlie Sunrise | A local Aboriginal elder who reveals, through his role as a lore keeper, that many of Steven’s visions were of ‘true’ historical events, so to speak. |

| Dr Hope Michaels | The Director of the Institute of Maritime Archaeology in Western Australia, who publishes Steven’s scrapbook. |

Themes

| History |

|

| Racism |

|

| Media |

|

| Identity |

|

Synthesising task

Book review

Students can write a review of the novel as a way to express their response to its ideas and construction. Explore some of the reviews in the More Resources section, or use websites like ReadPlus, CBCA Reading Time and Kids’ Book Review as a model. Develop students’ understanding of the review genre, ensuring they extend beyond pure affective response and instead provide thoughtful discussion of the text and its significance to the lives of young adults. A model for planning a review is available (PDF, 93KB).

(AC9E9LE02) (AC9E9LE03) (AC9E9LE04) (AC9E9LE05) (AC9E9LY06)

Book trailer

For the more technologically savvy, students can produce a book trailer instead. Using a platform of their choice, students can create a multimodal review that incorporates music, voice-over, text, stills and/or moving images to develop a thoughtful response to the novel. Students have only a few words in which to capture the essence of the book and its themes and so should use various multimodal elements to contribute meaningfully. The following resources may be useful:

Narrative elements

Structure

The Prologue, Hope Michaels’ notes, might seem in some ways to be a kind of spoiler, as it reveals all the main mysteries of the text: the pot and hand, the missing ring, Steven’s disappearance. Brainstorm reasons why the novel opens in this way, such as:

- It introduces these mysteries, but certainly doesn’t explain them, thus generating reader interest.

- It adds to the verisimilitude of the novel, lending it an appropriate air of authenticity and credibility.

- It sets the context for the following, fragmented, narrative. If the novel actually began with the Items in Steven’s scrapbook, the reader might be bewildered.

- It blends fact and fiction, thus setting up one of the major themes of the novel.

Possible intertextual connections could also be made to texts such as Shakespeare’s plays, which also include a prologue that outlines the action of the play.

Pose students the question of how Gary Crew has created structure out of these individual Items. Introduce the conceit used by Crew to create a structure for his epistolary novel: that Steven Messenger has collated these narrative fragments into a scrapbook, creating a sequenced narrative, which has then been added to and published by an ‘expert’, Hope Michaels. Provide each small group with a photocopy of the first ten Items, separated. Have them experiment with rearranging the Items, exploring the impact on narrative structure and the impressions readers might gain if they were presented in an alternative order. In turn, each group should report their findings to the class. Conclude with some focused writing, commenting on the impact of structure on shaping reader response.

Crew makes extensive use of parallels and contrasts in this novel. Have students identify connections between the various characters, for example:

- In Item 20, Steven complains he is ‘feverish and wheezing’, and in Item 21 Jan Pelgrom also has ‘fever and fluxes’.

- In Item 18, Jan Pelgrom assumes the Aboriginal people will ‘kill us and eat us’. In Item 2, Steven refers to the pot as the ‘cannibal pot’.

- In Item 21, Wouter Loos notes that Jan glows ‘with a soft light’, and Steven frequently sees his ‘movie star self’ bathed in a glow. Ela’s mother is described as having her hair floating around her ‘like a circle of gold’ (Item 17) and the cave art depiction of Jan has ‘yellow paint, like a halo’ (Item 29).

- Both Steven and Jan Pelgrom are afraid of the Aboriginal people they meet, for example Steven in Item 20 and Jan in Item 21.

- A number of characters make assumptions about others: Steven makes unflattering characterisations of Aboriginal people in Item 4, Jan Pelgrom believes the Aboriginal people are Indian cannibals in Item 18 and Hope Michaels assumes Steven has ‘a serious psychological condition’ in the Afterward.

- Both Steven and Nigel Kratzman live in single parent families (Item 6).

- Steven becomes fixated on the skeletons of creatures, for example in Item 28, whilst Charlie Sunrise is also connected with skeletons via the X-Ray paintings he cares for in Item 29, a connection Steven himself notes. Steven and Charlie also share the same ‘secret place’ on the headland.

- Examples of so-called factual history being refuted are also numerous, such as in Items 25 and 26, where the story of two ‘child castaways’ is first told as fact by one ‘expert’, then refuted by another.

After brainstorming a number of these parallels, use the ‘think-pair-share’ method for students to mind-map the various reasons for the parallel, such as the ideas it suggests about history or the human condition, and the way it functions to create textual cohesion in a fragmented narrative.

Characterisation

An important factor to consider with students are the implications upon characterisation that arise as a result of the fragmentary nature of the novel itself. Readers have to piece together clues about a character such as Steven through the various Items. Complicating this further is the fact that Steven is an unreliable narrator. Have students draw up a table with four columns, headed:

- What Steven tells us about himself.

- What Steven’s actions and speech reveal about him.

- What other characters say about him.

- What the parallels to other characters suggest about Steven.

This task could be split amongst groups of students, so that different students look at different Items and then compile the overall list as a class. Importantly, highlight the instances where Simon reveals himself to be an unreliable narrator, such as when he says his dad is away, but his mother reveals that his father is, in fact, dead.

Using the ClassTools ‘Fakebook’ resource, students are to create a social networking page for Steven Messenger. The focus should be on using only direct information from the novel, or inferences based on textual evidence. The profile should flesh out Steven’s character, with reference to his relationships, actions, feelings and thoughts. These can be reflected in the different sections of the ‘Fakebook’ profile: relationships, status updates, likes and so on. With careful planning, students can actually demonstrate a thoughtful, complex understanding of character through such a profile.

Alternatively, students could write the ‘Missing Persons’ report for Steven Messenger. A sample template (PDF, 50KB) is available. This would require students to search the text for details about Steven’s appearance, state of mind, history and motivations, as well as factual details such as location last seen.

Develop the previous discussion into a discussion on reliability of narrators. Which narrators seem reliable? Why? Why is Steven not seen as reliable? What clues are there, however, that Steven maybe is telling the truth? For example, his inexplicable return to the motel after the incident in the sinkhole, the fact that the content of his visions are made manifest in the cave paintings in the sinkhole, as well as his subsequent disappearance, suggest perhaps some veracity to Steven’s version of events. On the other hand, many other seemingly more reliable narrators are undermined, such as:

- Prof. Freudenberg, the translator of Loos’ journal in Item 15, who is undermined by the letter to the editor in Item 16

- Jill Boxtel, who introduces Item 25, is discredited by the writer of Item 26

- Wouter Loos himself states that ‘his intentions at all times [have] been for the good’, despite Item 10 revealing Loos’ status as a murderer.

The Afterword even reveals that Nigel Kratzman is not this character’s real name. What are the implications here for readers? Why might Crew be overtly discrediting each narrator, particularly those whom readers might deem more authoritative?

Conduct a guided close reading of Item 34. Consider the implications of Steven’s views on his and others’ behaviour as indicated by this Item. Explore the idea that novels, especially those featuring young adult protagonists, very usually chart the protagonist’s growth and development. Consider whether this is the case with Steven, and the implications of possibly limited development.

Setting

Select passages that feature strong descriptions of settings. Examples include:

- Item 6 (the Midway Roadhouse and surroundings)

- Item 11 (the cliffs near the Midway Roadhouse)

- Item 15 (the beaches and surrounding landscape in the coastal Mid West region of WA)

- Item 29 (the salt lakes, ranges and valleys of the Mid West region)

Conduct a close reading of these passages, focusing on the language and selection of detail that create a strong image of these settings. Ask students what comes to mind when imagining these places. Search for images on the internet for the Mid West and Murchison regions of WA. Have students match the descriptions of setting with the images they locate, combining them in a document or digital presentation. Students could write an evaluation of the effectiveness of Crew’s choices in language in capturing a sense of setting.

Language and style

Language skills

Develop students’ language skills (particularly those within the Year 9 Language strand) through a close exploration of the language used in an early section of the novel, such as Hope Michaels’ Prologue.

Create a close reading exercise by photocopying these pages, enlarging them and using white-out to remove several words. Select words from a range of word classes. By reading the whole sentence, students should be able to supply an appropriate word for each missing word.

On the same photocopy, highlight more challenging words, such as ‘exhausted’ (as in finances), ‘conventional’, ‘protruding’, ‘perusal’, ‘absconding’, ‘inconclusive’ and ‘breaches’. Have students predict the meanings of these words based on contextual reading before checking their answers in a dictionary. Compare the predicted meanings with the dictionary definitions and account for any differences with the intended meanings.

Explore the use of clauses and phrases to add further detail in sentences by breaking down some of the complex sentence structures used by Hope Michaels, such as:

On 29 August 1986, when 16-year-old Steven Messenger was reported missing from his mother’s trailer unit at the isolated Midway Roadhouse, Highway One, Western Australia, local police treated his disappearance as a routine case of a “short-term runaway”, believing that he would probably return when his limited finances had been exhausted (Prologue).

Reduce the sentence to its stem (‘local police treated his disappearance’) and write it on the whiteboard, and then gradually add clauses and phrases to add further information. Ask questions as prompts:

- How did local police treat his disappearance? (As a routine case.)

- As a routine case of what? (Of short-term runaway.)

- What else did they believe? (That he would probably return.)

- Return when? (When his limited finances had been exhausted.)

- When did the police make this statement? (29 August 1986.)

- Why then? (It was when Steven was reported missing.)

- Missing from where? (His mother’s trailer unit.)

- Where is that? (At the isolated Midway Roadhouse, Highway One, WA.)

Next, have students break down another sentence on their own, differentiating between phrases and clauses.

Use this section to also teach the use of more complex punctuation, such as the correct use of parentheses, dashes, hyphens, etc.

Narrative voice

Compare the style of language used across the different narrative voices. Provide small groups with a photocopy of an individual Item. Different groups should have Items that reflect the different narrative voices: Wouter Loos, Hope Michaels, Steven Messenger, news media, etc. Glue these Items to the centre of an A3 sheet. Have students annotate the Item, making comments about:

- complexity of sentence structure

- complexity of vocabulary

- register (formality)

- tone

- degree of descriptiveness

- the ratio of literal to figurative language

- the ratio of opinion to (supposed) fact.

Pin these around the room and use as the basis for discussion about the voice created for each of these narrators, focusing on the effects that arise as a result of the construction of voice. For example, who seems more credible?

Discourse

Conduct a close reading of Item 2 to analyse the use of the discourse of horror, noting:

- the metonymy of gloom and shadows

- the pathetic fallacy of the stormy weather

- the circle around a bonfire

- the telling of ‘ghost stories’

- personification of wind as ‘moaning’

- references to blood

- the description of the students as ‘a circle of the dead’

- Steven’s admission there was ‘something wrong about that place’

- the cannibal pot and mummified hand

- the description of the opening of the pot with its foul stench.

Students should annotate the text to highlight these elements. Lead into a discussion about intertextuality and why we might be familiar with these horror genre conventions. Have students suggest other examples of the use of similar discourse. Discuss the implications for reader positioning, particularly so early on in the novel. This activity could then be repeated with other Items to explore journalese, reportage or the discourse of other genres.

Symbols and motifs

Authors use symbols in their writing to create additional layers of meaning. Examine the following symbols within Strange Objects and consider the meanings that they add.

| Symbol | What it might mean | How it applies to Strange Objects |

| The ‘cannibal’ pot | ||

| The mummified hand | ||

| The ring | ||

| The abandoned mission | ||

| Blinding light | ||

| Aliens | ||

| Fragmentation of the narrative | ||

| The whale | ||

| The Life Frame | ||

| Allusion to James Dean | ||

| Allusion to Psycho and Bates Motel | ||

| Steven Messenger | ||

| Hope Michaels | ||

| Charlie Sunrise | ||

| Ela |

Additional notes (PDF, 81KB) are available.

Additional activities

| Timeline | Using an online timeline creator, students can create a timeline of the events in the various narrative streams. The advantage of using an interactive online tool is that students can easily rearrange entries. This could be conducted as a collaborative activity as several of these applications allow multiple users to log in. Of course, students could just as easily create a static timeline of events on paper. |

| Genre recipe | Explore how Strange Objects blurs the lines between genres. Discuss the generic conventions associated with historical, epistolary, horror, supernatural, science fiction, mystery, diary, family (or YA) drama and thriller texts. Small groups of students could have a short period of time in which to research one of these genres on the internet and then report back to the class on the dominant features of such texts. Have students then write a recipe for Strange Objects that represents their views on the proportions of each genre evident within this novel. For example: 1 cup historical novel, 2/3 cup mystery, a dash of science fiction, add 1 angst-ridden teenager and so on. In small groups, students should be asked to justify their recipes. |

| Which character are you? | A common occurrence on many social networking sites is the ‘Which character are you?’ quiz, referencing popular books and films. Students could design a multiple choice questionnaire/quiz asking a number of personality-related questions, with alternate answers based on several characters in the novel, such as Steven, Jan Pelgrom, Nigel Kratzman, Wouter Loos, Hope Michaels or Charlie Sunrise. Students should then write the answer key, along the lines of ‘If you answered mostly A, you are Steven Messenger’, with a paragraph summary of the character. This is a fun way to encourage students to come up with a succinct evaluation of each character. |

| Hot-seating | The epistolary nature of this novel lends itself well to role-playing or hot-seating strategies to explore character. For example, students could script and act out an interview between Hope Michaels and Steven Messenger, as if he returned from being missing. Ask students to consider the sorts of questions Hope Michaels would want to ask Steven and relate this to her character’s motivations. Consider the types of responses Steven might give, and link these to his motivations as revealed throughout the novel. In scripting the interview, students should aim to replicate the character’s personality and language traits. Other pairings could include Steven and Kratz, Steven and Sgt Norman, Hope Michaels and Kratz, and so on. |

| Discussion and journaling | One interesting aspect of this novel is the fact that, to most, Steven Messenger is not the most likeable protagonist.

|

| Finding connections competition | Explore the ways that Crew creates cohesion within his fragmented narrative, by exploring the various parallels and motifs that are established throughout the text. For example, after reading the whole text, return to Item 2, and in particular the ghost stories about the hitchhiker killer and human remains left among the meat ant nests. Connect this to Item 34, where Steven reveals that the body in his ‘Life Frame’ mysteriously has vanished from the ant mounds, as well as the Afterward, where Kratz suggests that ‘maybe the Hitchhiker got [Steven]’ and that Steven’s aerial rod, belt buckle and ‘Life Frame’ were discovered ‘among ant mounds’. Note that Steven refers to ‘a bright ring’ of light, which becomes a recurring element of his visions. Set up a competition encouraging students to revisit the text and discover other such connections. |

Meanings in the text

Exploration of themes and ideas

Have students reflect independently on what they think the novel is about, writing a page in their journals in which they identify some of the key ideas developed in the novel. From this, generate a list of keywords that identify broad themes, such as history, truth, media, identity, racism, etc. Next, divide the class into groups, assigning each group a few items from a particular narrative strand. Their task is to extend the keywords from the brainstorm into more precise ideas, finding textual evidence to support these ideas. Using a different sheet of paper for each keyword, students should write down the ideas developed by their group and relevant quotes (or page references). Different coloured papers could be used for each theme. Finally, as a class, stick these sheets to the whiteboard or a pin-up board, grouping sheets of the same colour/theme together. Generate discussion of each group’s work and collaboratively organise and refine the ideas on the board. This will allow students to visualise the development of themes across the different strands.

Using this template (PPT, 64KB), have students construct a PowerPoint presentation that explores one theme from the text in detail. This is a guided framework encouraging students to develop their explanation of a particular theme. The instructions are included within the template, allowing students to work independently. It develops skills that will prepare students for writing an essay later in this unit.

Alternatively, students could complete this table (PDF, 65KB) on themes. Complete the first row via whole class discussion, the second in pairs and the remaining rows individually.

Have students develop their writing skills by setting one or more focus questions as an extended writing activity. Model effective paragraph structure and for students who require further scaffolding, provide sentence stems or topic sentences. Suggested questions include:

- Why is Strange Objects considered an epistolary novel?

- What is the significance of the fragmentation of the narrative?

- Steven dreams of being taken away by aliens. Who are the real aliens in the story?

- What is significant about the fact that everybody refers to the pot as the ‘cannibal pot’?

- Why does Crew include ‘sources’ of information, only to then include a second ‘source’ that challenges the first?

- Why is the ‘dream-Steven’ a better dressed and better looking, James Dean-like version of himself?

- What is symbolised by the failed German mission behind which the Aboriginal characters live?

- Are Steven and Kratz really friends?

- How does Gary Crew try to give the novel the appearance of being ‘real’?

- What is the significance of Gary Crew blending fact and fiction in the novel?

Addressing the Cross-Curriculum Priority: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures

Racism is another major theme in the novel and is explored in both historical and contemporary contexts. Students should think about what constitutes ‘racism’, before discussing with a partner and sharing as a class. Try to encourage students to acknowledge that racism goes beyond racial slurs and violence, but exploitation, paternalism, textual representations, stereotyping and marginalisation also constitute racist practices. With this in mind, students should search for examples of racism in the text, from a range of characters: Steven, the German missionaries, Wouter Loos, Jan Pelgrom, various historians in the text and so on. Again use the think-pair-share model to allow students to build a wide range of examples. Conclude with these focus questions:

- In what ways do Aboriginal people experience racism in the text?

- Several characters could be considered quite racist. Does Strange Objects endorse or criticise such racism? How can we tell?

- What are the implications of the fact that contemporary characters are racist as well as the historical ones?

- How does the casually racist language used by white characters work to disempower Aboriginal ones?

Conduct a close analysis of Items 21 and 23, comparing them in terms of the representation of Aboriginal people and culture. Item 21, an extract from Loos’ journal, reveals the Aboriginal people living in close harmony with the land, with a strong sense of community and positivity. Item 23, though coloured by Steven’s own racism, represents Aboriginal people living amongst the detritus of colonisation. This section is highly symbolic, as the Aboriginal people live behind a failed Mission that sought to ‘civilise’ them. Steven and Kratz need to walk through a graveyard to find the Aboriginal settlement, which is described as ramshackle. The correlation here is significant: European intervention was doomed to fail and resulted in the devastation of Aboriginal culture.

Additional activities

| Quote matching | Set a quote-matching exercise, whereby students are provided with two sets of cards, one set with quotes on them and one set with themes/ideas on them. Students match the quote to the idea/theme it best represents. These can then be used as stimulus for paragraph writing, with the theme/idea card being the basis of the topic sentence and the quote providing evidence. Students need to add the elaboration that follows the topic sentence and the explanation of the evidence. |

| Dramatic roleplay | Organise a dramatic incident to occur, perhaps involving other staff or drama students. It might be a simulated conflict or some crime being committed. It needs to be reasonably elaborate and have the element of surprise for the students. Afterwards, have them independently recall details, such as order of events, description of people involved, details that seemed significant. Have students review their recounts and sign them. You might even have one student roleplay as an investigator, taking statements from each student. Compare students’ accounts and lead a discussion of the factors influencing the competing accounts. |

| Research task 1 | Item 30 explores the beliefs of the local Aboriginal people regarding whales and the carcasses that occasionally wash up on beaches. In particular, the significance of such cultural beliefs is highlighted in Jan Pelgrom’s transgression by clambering about in the whale carcass. Have students explore the beliefs of the Aboriginal peoples local to their area, or invite an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander guest speaker to share some aspects of their culture. |

| Research task 2 | Research Australia’s Bicentenary, in particular the advertising and political rhetoric attached to it. The following resources may be useful:

Have students critique the very Anglo-centric version of Australian history constructed by these texts and consider why Crew may have been inspired to write a text that encourages readers to question the veracity of ‘official’ histories. |

| Media portfolio | Have students collate a portfolio of media articles that reflect the sensationalism frequently encountered in the news, particularly in tabloid media. Suggest particular topical issues for the students to consider, such as so-called ‘boat people’ or WA’s controversial shark cull. Compare these with the representation of the media constructed in Strange Objects. |

Synthesising task

Socratic Circles

Socratic Circles are a form of thoughtful student-centred discussion (more information is available from Read Write Think and Facing History & Ourselves). There is no requirement to come to agreement or a definitive ‘correct’ answer. Instead, the focus is on developing close reading skills, verbal communication skills, and a deeper understanding of the ideas of the text through the discussion of a variety of opinions. This should help students develop understandings beyond the initial ideas generated in the previous activity.

Divide the class into groups of eight to ten. Although Socratic Circles can work in a whole class situation, smaller groups will provide opportunity for greater participation for individual students.

Set each group a particular Item or Items as the focus for their study and discussion. Some suggestions are offered below. Students are to study their given Item closely as individuals. Encourage students to analyse the text and annotate it thoroughly.

On the day of presentation, split each group into two circles, the inner and the outer. The inner circle will discuss the passage first while the outer circle observes and provides feedback, before the roles are reversed.

As facilitator, teacher intervention should be kept to a minimum. Ask for the inner circle students’ initial impressions of the passage. Then ask a single open-ended question to initiate discussion, after which the inner circle students are responsible for maintaining the flow of conversation for ten minutes. Some suggested questions are offered below.

The outer circle members then offer their feedback on the inner circle’s discussion, assessing their performance and interaction. The teacher may facilitate this. The inner and outer circles swap roles and the process is repeated. At this point, students may be asked to write up their understanding of their group’s passage.

| Suggested item | Suggested question |

| Item 3 | What does this Item suggest about the nature of the media in Australia? |

| Item 8 | How might we interpret Steven’s dreams? |

| Item 13 | What can we learn about the nature of history? |

| Item 15 | What does the inclusion of Loos’ fictional diary suggest about history and truth? |

| Item 20 | What do we learn here about racism and its effects? |

| The introduction to Item 21 | What are the effects of misrepresenting history? |

| Item 23 | What can we learn about white Australia’s treatment of Aboriginal people? |

| Item 26 | What are the implications of who gets to ‘write’ history? |

| Item 29 | What do we learn here about the Aboriginal culture? |

| Item 32 | What does this passage reveal about the nature of friendship? |

Ways of reading the text

Different perspectives/theoretical approaches

Organise strong students requiring extension into small groups to investigate one of the following alternate readings of the novel. This could take place while the teacher is working the bulk of the class on previously outlined activities. Students should work collaboratively to become ‘experts’ in one alternate reading. After this, the rest of the class could be divided into small groups with one ‘expert’ sharing their group’s findings with their peers.

A post-colonial approach

This novel was published originally in 1990, two years after Australia’s Bicentenary. This was a period of great reflection upon Australia’s history, particularly from a very Eurocentric perspective of celebrating the colonisation of Australia. However, such reflection also drew strong criticism, marginalising as it did Indigenous history and the nations whose earlier ‘discovery’ of Australia was overlooked. Explore the ways in which Strange Objects can be seen as subverting dominant versions of Australian history by:

- highlighting the fallibility and often contradictory nature of historical accounts

- implying that history is constructed, a pastiche that ultimately serves the interests of some whilst marginalising or even silencing others

- revealing the treatment of Aboriginal people at the hands of colonising Europeans and the resultant social issues that continue to be problematic

- suggesting that history repeats itself, particularly in regards to human nature, thus providing a gloomy vision for the future

- revealing the role of language in perpetuating racist and marginalising attitudes towards Aboriginal peoples.

Developing this approach further, question whether Crew’s novel does enough to acknowledge Aboriginal histories and cultures, or whether his privileging of white voices in the novel continues to marginalise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures. Furthermore, do his representations of the dangerous landscape and Aboriginal culture perpetuate the ideologies of colonialism?

A gender approach

There are several strong female characters in the text: Steven’s mother manages a roadhouse on her own, Dr Hope Michaels is obviously well-educated and heads up a respected institute – even Ela survives a shipwrecking. Students could be invited to compare how the female presence within the text compares to those of males. Explore the ways in which Strange Objects can be seen as challenging traditional stereotypical representations of women by:

- presenting strong female characters from both the domestic and professional spheres

- highlighting the marginalisation of women in history through the presence of the character of Ela and the symbolism of her lost language

- treating males who abuse women, such as Wouter Loos, unfavourably

- constructing female narrators as more reliable than males.

Developing this approach further, question whether history is still seen as created or ‘owned’ by males in the text. Hope Michaels may curate history, but the artefacts are found by males, the documents translated by males, and male voices dominate.

Additional activities

| Reading circles/panel discussions – an intertextual approach | Set students a personal reading challenge to read a second novel which they will then discuss in small group panel discussions. Each group will have a different focus and students need to select their novel accordingly. Suggested group focuses are: novels that deal with Australia’s history, other examples of the epistolary genre, other open-ended or unresolved novels, other novels with unlikeable or unreliable narrators, and so on. Panel discussions should focus on the students discussing how their chosen novel compares with Strange Objects, citing differences and similarities as well as articulating and justifying their personal preferences. |

| Class discussion – a contextual approach | The novel is set within an isolated stretch of Highway One. The landscape is harsh and unforgiving, yet this reflects an often-romanticised image of the Australian Outback. Discuss whether this setting is representative of Australia and the role of the Outback in our national identity. Locate other texts that romanticise the Outback. ‘Highway One’ suggests that this is a road of national importance, and the story takes place ‘midway’ along this highway. Prompt students to consider this symbolism: roads often represent a journey. What might Crew be suggesting is Australia’s ‘journey’? What is significant about being at the midway point? |

| Debate – a contextual approach | After closely analysing the text, form students into teams to debate the topic that Strange Objects is an accurate representation of Australian culture’. Members within each team could focus on different aspects, such as landscape, attitudes towards Aboriginal peoples, gender roles, media and so on. |

| Wiki – an evaluative approach | Use a ‘safe’ wiki site such as Edmodo to set up a wiki page to which all students can contribute. Set students the challenge of arguing why Strange Objects should be included in their Year 9 course. Students should collaborate on the wiki, providing and justifying reasons for studying the text. |

Identifying and justifying language/stylistic techniques for specific narrative or dramatic purposes

Clarify with students the various effects resulting from the fragmentary nature of the novel, such as:

- highlighting the competing/contradictory nature of historical accounts

- its metafictive technique of drawing attention to the constructed nature of the text, reflecting the constructed nature of both history and identity

- providing the appearance of balance through the inclusion of multiple narrative voices

- its connections to the epistolary form, allowing the interior journeys of Steven and Wouter Loos to be conveyed simultaneously

- the sense of verisimilitude arising from the inclusion of ‘documentary’ evidence.

Encourage students to write an extended response in their journals exploring one (or more) of these purposes.

Rich assessment task 1

Ela’s journal

Adopting a gendered reading practice, students are to compose their own ‘historical journal’ presenting the story of the character of Ela. In order to do so, students will need familiarity with the text to accurately represent Ela’s story as revealed through Steven’s visions and Wouter Loos’ journal. However, by reading the ‘gaps’ within the narrative, students will be able to develop her history and character beyond the marginal representation she receives within the novel. As part of the task, students should write their own ‘Foreword’ that contextualises Ela’s story and its discovery. Particular students may be extended by producing an additional ‘Item’ or two that reveals this back story and commenting on the implications of the original silencing of female voices within historical accounts. The writing process should be seen as a significant element of the task, with students demonstrating appropriate planning, drafting, proofreading and editing. The task also provides the possibility for research as students investigate Ela’s historically likely origins.

Download the assessment rubric (PDF, 63KB).

Synthesise core ideas

Students should return to their earlier journal writing where they reflected on the novel after their initial reading. Alternatively, you may choose to return to the point where students made their predictions after reading the Foreword. Having now studied the text, students should reflect on their earlier comments and write a response, noting how their first impressions have changed.

Create a knowledge tree on a large blank wall in the classroom to create a striking visual representation of students’ learning. Cut out a large tree trunk from cardboard with four main branches. Label the trunk ‘Strange Objects’ and each branch with ‘Narrative conventions’, ‘Themes and ideas’, ‘Historical context’, ‘Readings and responses’ (or categories of your own devising). Each of these main branches will then further divide into subcategories. For example, ‘Narrative conventions’ would divide into ‘Character’, ‘Setting’, ‘Structure’, and so on. Cut leaves from sheets of green copy paper. Collaboratively, students plan and devise the aspects of their learning that should be recorded in the knowledge tree, before allocating these according to students’ individual expertise. Students take responsibility for particular aspects of their learning, summarising key findings on a leaf. For example, one leaf might be devoted to a brief explanation of the epistolary form, or another on the character of Charlie Sunrise, etc. The leaves are added to the tree to provide a representation of the class’s experience.

Alternatively, the knowledge tree can be set up at the beginning of the programme of teaching and learning. As different aspects of the novel are explored, students could add leaves to watch the tree ‘grow’ as their knowledge and understanding does.

A digital alternative is to create a wiki, using a ‘safe’ site such as Edmodo, that allows students to collaborate and create a Wikipedia-style entry for the novel that draws together the core ideas.

Additional activities

Allow students to select one or more activities from the activity sheet below, which is organised according to Bloom’s Taxonomy of learning domains. Encourage students to consider the higher order skills but use the Taxonomy to differentiate for students’ varying abilities.

| Create | Design a podcast that discusses the implications of this novel and its comments on intercultural relationships for 21st century Australia. | Roleplay an interview between Steven Messenger and Hope Michaels, as if he was found 12 months later. |

| Evaluate | Discuss with a partner whether Strange Objects challenges or reinforces stereotypes regarding Aboriginal people. Record your discussion with a webcam or mobile phone. | Write a letter to your teacher explaining why Strange Objects should be included in the Year 9 course, and what can be gained by studying it. |

| Analyse | Design an assessment task that assesses your classmates’ understanding of one of the themes in Strange Objects. As part of your task, design the marking guide that outlines what students would need to demonstrate. | Conduct a close analysis of one or more connected Items, annotating them to show how their construction influences the readers’ understanding of character or theme. |

| Apply | Create a reading list of other texts that address similar themes to Strange Objects. For each entry, provide a brief explanation of their connections. | Retell the story of Steven Messenger as observed through Nigel Kratzman’s eyes. Present this in the form of a dialogue between Nigel and Sgt Norman. |

| Understand | Create a table that compares the narrative strands of Steven Messenger and Jan Pelgrom. | Reimagine how Strange Objects might be structured in the digital age. Rather than a series of journal entries, how might a teenager today construct this epistolary text? |

| Remember | Create a comic strip to illustrate five key scenes from Strange Objects. | Create a series of flashcards to help you remember key events in Strange Objects. |

Students should reflect on their learning across the previous weeks. Responding in their journals, students should comment on their personal progress and participation in their learning, the activities they enjoyed and/or did well in, new skills and understandings they have acquired and topics for revision. In addition, they should set a learning goal for their next unit of work by considering an area in which they felt they could have improved.

Rich assessment task 2

Essay

Students are to write a timed, in-class essay exploring how the construction of the text has contributed to their understanding of one of its themes. Students are to pick one of the themes that they have explored in Strange Objects and write a six-paragraph essay (introduction, four main body paragraphs, conclusion) in which they explain how their understanding of that theme has been influenced by one or more conventions employed by Gary Crew. Each main body paragraph should explore an aspect of their understanding and connect it to one or more conventions, providing textual evidence.

You may wish to allow students to plan the essay at home (or in a prior lesson) and bring their plan into the assessment with them. The sample template below is provided to assist students in planning their essay.

Introduce the novel by title, author and genre

Introduce the theme to be explored

Plan main body paragraphs, connecting ideas to conventions used

| Paragraph | Specific idea about theme | Conventions used to show this | Quotes to support this idea |

| 1 | |||

| 2 | |||

| 3 | |||

| 4 |

Download the assessment rubric (PDF, 71KB).

(AC9E9LA03) (AC9E9LA04) (AC9E9LE02) (AC9E9LE03) (AC9E9LE05) (AC9E9LY06)