Introduction and background

First performed in 1955, Summer of the Seventeenth Doll has become an Australian classic, praised for its accurate portrayal of ‘ordinary Australia’. Its sense of authenticity springs from the way situation, characterisation and language depict a turning point in how Australians saw themselves and were seen by others.

Summer of the Seventeenth Doll was the first Australian play to tour internationally and enjoyed an award-winning season in England, as well as a less popular one in New York. Despite this, the film rights to the play were purchased and Season of Passion was released in 1959.

In 1994 the play was turned into an opera by Richard Mills (composer) and Peter Goldsworthy (librettist). The Victorian State Opera premiered the work at the Playhouse, VAC, on October 21, 1996.

Context

Australian society in the 1950s

To be able to appreciate the tensions within this play, students need to understand the social conditions of the 1950s, particularly:

- gender roles

- attitudes towards sexual morality

- traditional notions of Australian identity.

These can be researched in the usual ways but if time is short, the Belvoir Theatre’s Teacher’s Notes on Summer of the Seventeenth Doll provide a comprehensive source of information and activities.

Ray Lawler, in his introduction to the 2012 edition of the play, also draws attention to aspects of life in the 1950s that are key to understanding the play, including:

- the nature of cane-cutting and the role of the ganger

- disapproving attitudes to the job of barmaid

- the important social function of the boarding house

- an explanation of the kind of kewpie doll that filled fairgrounds at the time and dazzled young girls.

The National Archives of Australia provides background of the play and an image of Ray Lawler.

Reading in performance

Set

Lawler’s description of the set is precise, detailed and contains commentary. Have students:

- Draw their interpretation of the scene.

- Compare their drawing with others’ drawings.

- Using these initial ideas, as a class arrange the furniture in the room to form a rudimentary set.

Costume

After scanning examples of 1950s clothing, students bring in items to be used as identifiers for each character. These are to be worn during the initial reading.

Scenes

Students will need to read the play or view a performance, but for the purposes of study, the following scenes have been identified as key to the development of the action and emotion of the play. These scenes can be distributed to groups for presentation in the class, along with the preparation activities that follow.

ACT 1

Scene 1

OLIVE: That mother of mine should be home by now . . .

OLIVE: Let’s have another drink on it.

PEARL makes a grateful escape and OLIVE turns back to BARNEY . . .

OLIVE: I’d have gone lookin’ for you with a razor.

Scene 2

ROO: . . . Come on in Bub – how are you? . . .

ROO: Drop it or I’ll bash your face in.

PEARL: Well now, more to it than that of course . . .

BARNEY: Well, no point rabittin’ on ’bout that. Here’s Olive.

ACT 2

Scene 1

PEARL: Who are the Morrises then? . . .

BARNEY: Nothin’ to it.

BARNEY: How’s the paint business today? . . . end of scene.

Scene 2

BARNEY: Lissen, me and Johnnie – . . .

BARNEY: Pearlie?! Pearl?!

BARNEY: Forget her. Let me introduce you – see this feller, Bub? . . .

She responds with a nod and a radiant smile.

BARNEY staggers, recovers his balance and – aware now that he must justify his actions – drops any pretence of drunkenness as a cover . . . end of Act 2.

ACT 3

ROO: All the – you’ve taken down all the stuff? . . .

She moves to leave the room and ROO stays her with a tired gesture, the beginnings of acceptance.

ROO: Got to say I never knew any cryin’ woman look worse than you do . . .

end of play.

Scene preparation activities

In their performance groups, students will need to consider:

- the motivation of their character in the scene

- the objective of their character in the scene

- how that objective contributes to the super-objective of the character, i.e. their ultimate desire

- what obstacles to achieving the character’s objectives need to be overcome

- what the character is doing in the scene to achieve these objectives/overcome any obstacles

- what approaches will be needed to clearly realise that character on stage and make these aspects clear to the audience.

Students should:

- write these up as director’s notes for the scene and provide them for other students to read

OR

- present them verbally before or after enacting the scene.

These director’s notes, in addition to the presentation, form the basis for peer review or feedback. Feedback discussion could involve such issues as:

- the validity of the interpretation of the scene

- how effectively this interpretation was rendered by the movement, gestures and speech of the characters, their interaction with each other, and with the set

- suggestions for other interpretations of the scene in keeping with the themes and super-objectives of the characters.

Synthesising task/activity

Mapping the action

In groups, students should:

- Map the action of the play in terms of its emotional intensity. This is most easily done through a bar graph and there are many free graphing tools on the web. To allow maximum comment, you can arrange text boxes horizontally in Word, with the details of the scene written in each bar.

- Identify points of crisis.

- In a brief statement (about 150 words), consider how the play works in terms of its dramatic structure.

Senior English Unit 4

(ACEEN060) (ACEEN061) (ACEEN062) (ACEEN063) (ACEEN069) (ACEEN070) (ACEEN075) (ACEEN076) (ACEEN079)

Literature Unit 3

(ACELR038) (ACELR039) (ACELR040) (ACELR042) (ACELR044)

The writer’s craft

Character

Have the students create a sociogram of the characters in the play. Inspiration software which allows ‘Notes’ for each character would work well with this activity.

- For each character, students answer the following questions:

- What does the character say about him/herself?

- What does he/she say about the other characters?

- What do other people say about this character?

- What objective assessments are given about the character by the playwright through the stage directions?

Language and style

The play script

The text of a play is different from the text of a novel or poem in that the latter two are presented as a totality. On the other hand, ‘[P]laytexts . . . are actually pre-texts to performance, closer relatives to musical scores than to purely verbal artifacts like novels or poems, and the script is no more the play than a score is the symphony’ (Brown, 2000).

Much of the meaning for an audience is conveyed through tone, movement and gesture, some of which are specified in the stage directions but many vary from production to production. Lawler’s instructions are particularly detailed and he takes the trouble to clarify much of the characters’ inner thoughts; for example, ‘BARNEY staggers, recovers his balance and – aware now that he must justify his actions – drops any pretence of drunkenness as a cover‘ (Act 2, Scene 2).

Students can experiment with different tones and gestures for a range of lines in the play to see how meaning may be affected. For example, the lines below are uttered by Pearl, a master of innuendo and sub-text, and can be made to change significantly:

Act 1, Scene 1

PEARL: [broodingly] Mmmmm. Well, I’m fond of a good book myself now and then.

PEARL: [sharply] I don’t have to fit in. What I am here for is a . . . a visit . . .

PEARL: [stammering] Yes. Olive did mention – I’m Mrs Cunningham. How d’yer do.

Act 1, Scene 2

PEARL: You might like to take my bags upstairs.

Act 2, Scene 1

PEARL: Well, after all, who would want to knit a sweater for an eagle.

Australian English

The language of The Doll is distinctively Australian, particularly reflective of the group now known as ‘Aussie battlers’ – not affluent but straightforward and decent.

Lawler captures the speech of the working class of the early 1950s through his use of plain speech, phonetic spelling and colourful idiom.

Student activities

Have students view the ABC 7.30 report, The Doll to tour Australia again. Compare the language and accents of the characters in the play to that of Ray Lawler in each

of his interviews (1971 and 2011). To what extent does this difference imply that this is a play about class?

One of the greatest appeals of the play is its use of Australian idiom. Have students read the interview with Ray Lawler from Meanjin (page 33) and, noting examples from the text, consider in what ways the Australian vernacular has changed over time.

Metaphor and symbol

Using examples from texts that students have previously studied in class, explain the difference between cultural symbols and symbols that are specific to a particular

text. Ask them to identify objects and colours in the play that are potential symbols (including set and costume), noting their cultural symbolism and then considering the

extent to which these symbols differ in their meaning within this text.

Themes

Growing up

Katherine Brisbane, in her introduction to the 1978 edition of The Doll, asserts that the play is ‘about growing up. It is about growing up and growing old and failing to grow up’. Students can consider this theme of the play, by finding examples to support this reading through:

- The set:

- For example, the theme of the play is signalled in the first words in the description of the setting, ‘charming and fast-vanishing relics of Victorian architecture’, and reinforced by its setting in Carlton, ‘a now scruffy but once fashionable suburb of Melbourne’.

- The outdoor shrubbery is described as ‘wild’ and ‘overgrown’, ‘enshrouding’ the interior, the last bastion of cheerfulness. The furniture seems randomly selected and placed but the whole is held together by the brightly coloured fairground paraphernalia.

- The characters:

- For example, Olive’s first entrance, dressed symbolically in ‘a crisp green and white summer frock’ and showing ‘an eagerness that properly belongs to extreme youth’, presents an appearance which is somewhat inconsistent with her age and ‘surface cynicism’.

- The action:

- For example, at the end of Act 2, Roo pulls the vase containing the seventeenth doll from Barney’s hands in anger, smashing it and scattering the dolls. While the action is a childish one, it indicates Roo’s recognition that the quality of his past life and relationships is over and that the time has come to grow up.

Having found and articulated how these examples are illustrative of the theme, students can write scenes that occur outside the action of the play:

- in the sitting room where Nancy tells Olive she is getting married

- in the cane fields where Roo falls

- in the pub where Barney convinces Johnnie to come to the house and clear the air with Roo.

Students can also consider whether or to what extent the situation would have led to a crisis if one of the following had occurred:

- Nancy had not got married

OR - Roo had not fallen on the cane field.

They can also write scenes which occur after the play, such as a meeting one year later between:

- Olive and Nancy

- Barney and Nancy

- Roo and Emma

- Bubba and Emma.

Shattering of illusions

Growing up in this play involves coming to terms with reality and the development of self-knowledge. Tragically for Roo and Olive, this means the shattering of their illusions about themselves and their place in society and the natural cycle of life. The issue is brought to a head through characters’ conflicting perceptions of reality, most obviously Olive’s and Pearl’s, but also that of the other outsider in the play, Johnnie Dowd, who ‘just can’t see’ what Roo and Barney see in the place.

Students should go through each scene of the play in groups or individually and collect references to seeing, blindness and how things ‘look’. This task can be divided among them. They can also consider this theme in relation to the three generations represented in the play.

National identity

Katherine Brisbane adds that the play is not simply about the characters but Australia itself, which in the fifties was ‘at the watershed of our national consciousness’. Australia was changing dramatically after the Second World War with the waves of European migration and the drift from a rural to an urban society. Roo and Barney, as itinerant canecutters, sit at the cusp of this change as their lives oscillate between outback hardship and the city highlife.

Students can consider the associations with and connotations around the ‘outback hero’, as Olive sees Roo. They should note the implications for the Australian archetypal character in a sunburst such as the one here, and do the same for the ‘city man’ as perceived by Olive in the play. Students then discuss:

- how close these are to reality

- whether the play endorses either of these extremes.

Gender roles in society

For Olive, Roo and Barney, the lay-off was ‘a time for livin”, in contrast to the rest of the year, ‘seven months . . . [of] killin’ themselves’. The lay-off was a time when Roo and Barney were ‘two eagles flyin’ down out of the sun’, paragons of masculinity basking in Olive’s and Nancy’s adulation. As time wore on, Nancy realised that the time for this ideal was over and that this kind of man and this way of living was not sustainable.

Olive has rejected the traditional feminine role of marriage and children, opting instead for the idealised ‘party-time’ of the lay-off. She works in what, in the fifties, was a purely masculine world and demands the kind of freedoms only acceptable for men at that time. Her commitment is to the rugged masculine ideal and she finds Roo’s machismo flattering to her romantic self-image and a bulwark against any social censure. When Roo tries to redefine his self-image, Olive can only see its diametric opposite and with his change in identity, her own must crumble if she accepts his proposal of marriage.

The play begins with two unmarried women, Pearl and Bubba, discussing Nancy’s wedding. Pearl’s view that she ‘had her head screwed on the right way’ and that the women in the lay-off relationship could be seen as ‘cheap’ was very much the prevailing social attitude of the time. The play ends with the two men leaving a domestic setting, littered with broken dolls and shattered heterosexual relationships. Roo and Barney’s mateship has been restored but their roles have reversed as Barney guides Roo out into a new ‘all-male’ world with the final words of the play, ‘C’mon, boy’.

Students should consider such features of the play as:

- the use of separated masculine and feminine domains

- the place of domestic scenes in the play

- what the play implies about stable male/female relationships and single gender mateship.

Students then write an essay on the topic: How does the ending of the play realise its themes? To what extent can it be said to resolve its thematic issues?

Rich assessment task (Receptive mode)

Students choose a short extract from the play for performance with an ‘alter ego’ exercise (where one student plays the role of a character while another stands behind telling the audience what he is really thinking). The wisdom of their choice is critical to the success of this activity; for example, it would work well with Roo and Barney, who both have secrets from the other characters and the audience.

Students choose one of these performances as the basis for transforming the extract into narrative prose in which they:

- convey the action of the scene

- articulate the inner thoughts of a character

- create a narrative voice that can be sympathetic to or critical of the stance of the character.

It is a good idea to provide a prose model for students before they commence writing. Students can annotate an example from a section of a novel, such as the one below from James Bradley’s Wrack, to see how a writer can allow for the portrayal of both the internal and external situation by using:

- an omniscient narrator

- careful selection of diction that adds a descriptive layer to the action

- a focaliser

Claire and David met a year after Tania died, brought together by friends. A summer dinner party, the not-so-subtle manoeuvrings of their hosts. After dinner, the two of them had walked home through the warm streets together, half drunk, talking, and David had found himself relaxing into their tentative liaison, Claire’s undemanding presence giving him the room to unfold the battered vessel of his

heart. In the dark outside her flat she had taken his hand, and David had felt her lips on his cheek, and his body had trembled so violently he thought she must feel it, must know. So much tangle and bruise inside of him. But she had said nothing, just smiled and squeezed his hand, his skin remembering the cool pressure of her lips, fingers, as he navigated the orange-lit streets to his home.

On completion of their narrative, students can write a reflection on the activity, commenting on such things as:

- why they thought the scene would work well as prose

- what linguistic and stylistic features they used successfully

- any difficulties they found in writing the transformation.

Senior English Unit 4

(ACEEN060) (ACEEN061) (ACEEN062) (ACEEN063) (ACEEN064) (ACEEN065) (ACEEN066) (ACEEN069) (ACEEN070) (ACEEN071) (ACEEN072) (ACEEN075) (ACEEN076) (ACEEN077) (ACEEN078) (ACEEN079)

Literature Unit 3

(ACELR037) (ACELR042) (ACELR043) (ACELR044)

Summer of the Seventeenth Doll – film

The Doll was the first Australian play to tour internationally. Following its debut seasons in 1955 in major Australian cities, it enjoyed great success in England, eventually transferring in 1957 to New York, where it was less appreciated. However, in 1959 the play was adapted to a film entitled Season of Passion, starring Anne Baxter and Ernest Borgnine as Olive and Roo. A review summary can be found here and an image of the movie poster can be seen here.

Students can consider how the movie poster implies a changed audience from the covers of the play text by comparing the 1978 edition with the 2012 edition.

Search for stills from the movie that take the play beyond the sitting room:

- lying on the beach

- at the boxing ring

- in the bar

and have students consider the same question of a changed audience.

This would also be a good time to examine the different demands of the change of medium from stage to screen, asking students:

- why the scene changes are necessary for the medium of film

- where in the play they think these scene changes were inserted

- whether they can identify other opportunities for adaptation of the play to film.

If you are able to track down a copy of the film, there would be value in having students consider:

- how other countries represent Australians in their cultural productions

- to what extent these representations capture Australian characters and society.

Tragedy

Remind students of the conventions of the tragic hero, such as his or her downfall being:

- brought about through own choices

- precipitated by an error of judgement

- not fully deserved

and that despite the heartbreak, the tragic hero gains self-awareness, so increasing his or her stature in the eyes of the audience.

Have students discuss in groups how these conventions are played out in Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, and then share their ideas with the class.

Divide the class in two to argue point-by-point, supporting this question with evidence from the text: who is the greater hero, Roo or Olive? (You may want to give them some extracts from Theatre notes to boost the case for Olive as the play script tends to support the case for Roo more strongly.)

Have students read this extract from Arthur Miller’s essay, ‘Tragedy and the Common Man’ (1949), and discuss the question: are the characters in Summer of the Seventeenth Doll tragic or merely pathetic?

There is a misconception of tragedy . . . the idea that tragedy is of necessity allied to pessimism . . . This impression is so firmly fixed that I almost hesitate to

claim that in truth tragedy implies more optimism in its author than does comedy, and that its final result ought to be the reinforcement of the onlooker’s brightest opinions of the human animal.

For, if it is true to say that in essence the tragic hero is intent upon claiming his whole due as a personality, and if this struggle must be total and without reservation, then it automatically demonstrates the indestructible will of man to achieve his humanity.

The possibility of victory must be there in tragedy. Where pathos rules, where pathos is finally derived, a character has fought a battle he could not possibly have won. The pathetic is achieved when the protagonist is, by virtue of his witlessness, his insensitivity, or the very air he gives off, incapable of grappling with a much superior force.

Pathos truly is the mode for the pessimist. But tragedy requires a nicer balance between what is possible and what is impossible. And it is curious, although edifying, that the plays we revere, century after century, are the tragedies. In them, and in them alone, lies the belief – optimistic, if you will, in the perfectibility of man.

Conventions of form and style

Have students brainstorm aspects of traditional bush values and characteristics (isolation, mateship, male society, physical hardship, courage in the face of adversity, anti-authoritarianism, dry sense of humour, reticence, understatement). They then take each of these qualities and, in groups, discuss which would be easy to enact on a traditional stage and which would be more difficult. They could consider:

- set

- action

- characterisation.

Have students go back to their map of events and emotional intensity in Summer of the Seventeenth Doll and consider their summaries of the play against the following features of realist drama, making notes about how the play conforms to these conventions.

| Convention | Realisation inSummer of the Seventeenth Doll |

| Use of the fourth wall | |

| Commonplace setting | |

| Serious treatment of contemporary themes relating to ordinary people | |

| Believable characters with understandable motivations | |

| Everyday language | |

| Clear logic of cause and effect | |

| A structure of exposition in the first act, action and intensity increasing through rising action in the second, and climax and dénouement in the third. |

Synthesising task

Students should synthesise this information to explain the following statement by Jane Cousins in her essay on gender and genre in Summer of the Seventeenth Doll: ‘What Lawler was able to do . . . was to bring the characteristic elements of the outback play (the bushman stereotype and the values of mateship and physical prowess) into the domestic interior of classic European naturalistic theatre.’

Senior English Unit 4

(ACEEN060) (ACEEN063) (ACEEN064) (ACEEN065) (ACEEN069) (ACEEN071) (ACEEN072) (ACEEN075) (ACEEN076) (ACEEN077) (ACEEN079)

Literature Unit 3

(ACELR037) (ACELR038) (ACELR039) (ACELR040) (ACELR042) (ACELR043) (ACELR044)

Synthesise core ideas

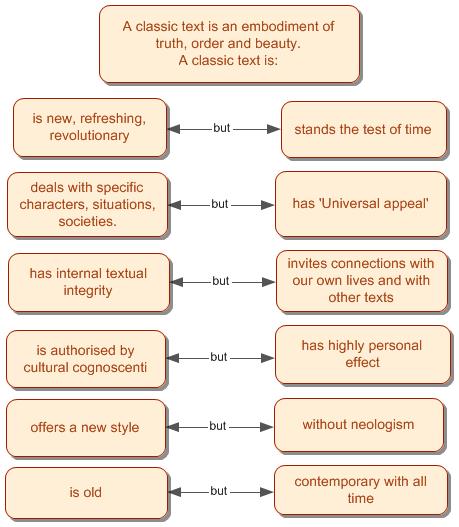

Summer of the Seventeenth Doll has frequently been called an Australian classic. ‘Classic’ is a word that is flung around as a fairly empty turn of phrase in everyday speech, yet students of English need to have a sense of the significance of the term and how a ‘classic’ text operates culturally. There has been much theoretical discussion about what makes a text a ‘classic’ that appear to offer a range of contradictions.

Italo Calvino, in his essay ‘Why read the classics?’, has a very modern take on the classic, one that students will relate to, in that he focuses on the personal aspect: ‘Your classic author is the one you cannot feel indifferent to, who helps you define yourself in relation to him (sic), even in dispute with him (sic).’

Ask students what qualities they think a text should have to be considered a classic, and possibly build up a mind map of their discussions.

Rich assessment task (Productive mode)

In groups, students are to contribute a section on Summer of the Seventeenth Doll to a website entitled: ‘Australian classics’. The purpose of the website is to promote Australian culture to Australians and to the world.

The website provides:

- an outline of the content of the text and its appeal to Australian audiences

- commentary on its ideas

- an overview of its role in and significance to Australian culture

- an explanation of how the play can capture the imagination of people around the world.

Students will need to:

- research reviews and images of productions

- write and hyperlink the copy

- create and insert film footage

- present the information in an entertaining way.

Students will need class time to organise their various roles in the group and could use such platforms as Wikispaces or Weebly, or simulate a website using PowerPoint. The materials are then uploaded for sharing.

Senior English Unit 4

(ACEEN061) (ACEEN062) (ACEEN064) (ACEEN065) (ACEEN066) (ACEEN069) (ACEEN070) (ACEEN075) (ACEEN076)

Literature Unit 3

(ACELR037) (ACELR038) (ACELR040) (ACELR044)