Introduction

Helen Garner is a prominent Australian author. One critic described her writing as ‘sparse, droll prose and clear-eyed intolerance for bullshit [that] can make me weep with its intensely personal evisceration of the world’s ills — its institutions, her enemies, herself.’ – Meanjin

Garner also crosses genres with short stories, fiction, articles and non-fiction. While much admired for her sparse and honest prose, she has also courted controversy at times: for The Spare Room which she classes as fiction, but that some critics claim is memoir; and for The First Stone, an exploration of a sexual harassment case at Ormond College, an elite Melbourne university college. More recently, the publication of This House of Grief, capturing the arduous trial of a man on three murder charges for driving his children into a dam, further illustrates Garner’s fascination and capacity to explore the most intimate and profound aspects of personal and familial relationships.

Further background information on Helen Garner and her work can be found below:

- Truly Helen: Fact or Fiction

- Helen Garner: Conversations with Richard Fidler (podcast)

- Helen Garner: Wikipedia

- What’s in a name: Helen Garner and the power of the author in the public domain.

Activity 1:

Context for The Children’s Bach: Helen Garner and Australia in the 1980s

From the resources above select significant details of Garner’s life and her literary works that you consider of relevance to this study and your students. In addition, provide students with a sense of the social, historical and political context of the time, using the resources below. This will build their contextual knowledge of Garner and Australia and the world in the 1980s.

- Buzzfeed: 39 signs you grew up in Australia in the 80s

- The Year 1984 from The People History (global)

- More power to the 80s, from The Australian, 7 December 2009

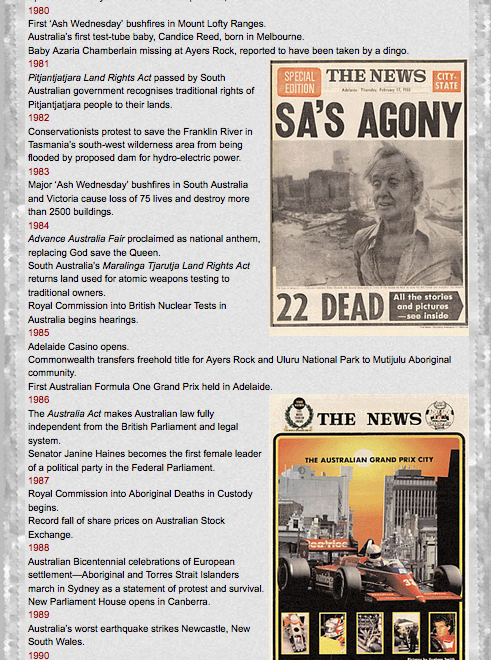

- The screen capture (below), from the State Library of South Australia Archives highlights some key events from Australia in the 1980s.

State Library of South Australia Archives

Group discussion and report:

Using on the resources above, and others they find online and through discussion with people who were adults in the 1980s, students are asked to draw some preliminary conclusions about domestic life in Australia during that time, based on what might be similar and different to life today. The goal here is to establish an understanding of the setting in which Garner situates The Children’s Bach and to establish it as an authentic domestic drama for its time.

The following are suggested topics for each group, with the teacher steering discussion to ensure relevance to the context of the novel:

- fashion and food trends,

- architecture/features of housing,

- home and personal technologies,

- music and entertainment trends,

- family/cultural demographics,

- political context including social support, immigration etc.,

- social/economic movements and reforms relating to feminism, education and employment.

(ACELR019) (ACELR020) (ACELR022)

Activity 2: Domestic scene at Dexter and Athena’s home in Bunker Street

Students read pages 1 to 21, using the following character list and map to support their initial understanding.

The Fox family who live in Bunker Street where most of the action takes place:

- Dexter and Athena (husband and wife);

- Billy (their son with undisclosed intellectual disability, possibly autism);

- Arthur (their son);

- Dr Fox and Mrs Fox are briefly present/mentioned in early and later pages.

Sisters who live in an unconverted warehouse:

- Elizabeth/Monty (Dexter’s 39 year-old ex-girlfriend, Vicki’s older sister);

- Vicki (Elizabeth’s 19 year-old sister who has recently arrived from Perth).

Father and daughter who live nearby:

- Philiip (rock musician, Elizabeth’s occasional boyfriend);

- Poppy (Philip’s 12 year-old daughter).

- During close reading, students are to identify two key quotes for each of the following:

- the qualities and traits of Dexter;

- the qualities and traits of Athena;

- the qualities and traits of Elizabeth;

- the qualities and traits of Vicki;

- the qualities and traits of Billy;

- the qualities and traits of Arthur;

- the domestic setting;

- the place of music, art or literature in the home;

- tensions arising between any of the characters;

- the context of the 1980s in Melbourne and/or Australia.

2. Form groups to share and examine the quotations selected, and students can then create:

- brief profiles of each of the characters (20-40 words max each, excluding quotations);

- brief description of the Fox’s home in Bunker Street (20-40 words max each, excluding quotations);

- brief description of how this novel is located in 1980s Melbourne and/or Australia;

- two predictions of what you believe will happen within the relationships (20-40 words maximum each, excluding quotations).

(ACELR020) (ACELR023) (ACELR031)

Students to be provided with timeline to complete reading the novel.

Introduction

In this close study of The Children’s Bach, students will focus on each of the following:

- sentence structures (Activity 1),

- the voice of the omniscient narrator (Activity 1),

- the use of journals and everyday observations to create fiction/non-fiction texts (Activity 2).

Whilst the majority of students will have come across each or most of these aspects of textual analysis and creation earlier in their schooling, for many it will provide useful revision and extension.

Close Study

Sentence structure, rhythm, meaning and identification of point of view

The notes and links provided here regarding sentence structure and narrative point of view may provide useful revision/extension reference for students.

It is vital that students understand each of the follow language features as more than simply technical devices. At the heart of literary analysis is the reader’s examination and reflection on how the writer uses language (here, sentence structures and point of view) to construct the text, and the effect of this on the reader. How effective is this technical skill of the author in influencing our interpretation and response to the text?

Revisiting the grammar of sentence structures

The following revision supports the analysis and discussion of the impact of sentence structures on the quality of writing:

Simple sentence: has the form of a single clause (e.g. ‘David walked to the shops.’ or ‘Take a seat.’) From Australian Curriculum English Glossary.

First introduced into the Australian Curriculum English at Year 1: Simple Sentence: Identify the parts of a simple sentence that represent: ‘What’s happening? What state is being described? Who or what is involved?’ and the surrounding circumstances.

(ACELA1451) (EN1-4A)

Clause: a grammatical unit that refers to a happening or state (e.g. ‘The netball team won’ [happening], ‘The cartoon is an animation’ [state]). A clause usually contains a subject and a verb group/phrase (e.g. ‘The team [subject] has played [verb group/phrase] a fantastic game’), which may be accompanied by an object or other complements (elements that are closely related to the verb – e.g. ‘the match’ in ‘The team lost the match’) and/or adverbials (e.g. ‘on a rainy night’ in ‘The team won on a rainy night’). From Australian Curriculum English Glossary.

First introduced into the Australian Curriculum English at Year 5: Understand the difference between main and subordinate clauses and that a complex sentenceinvolves at least one subordinate clause.

(ACELA1507) (EN3-6B)

Main and subordinate clauses: a clause can be either a ‘main’ or ‘subordinate’ clause depending on its function:

- main clause does not depend on or function within the structure of another clause.

- subordinate clause depends on or functions within the structure of another clause. It may function directly within the structure of the larger clause, or indirectly by being contained within a noun group/phrase. From Australian Curriculum English Glossary.

Compound sentence: has two or more main clauses of equal grammatical status, usually marked by a coordinating conjunction such as ‘and’, ‘but’ or ‘or’. In the following examples, the main clauses are indicated by square brackets: ‘[Jill came home this morning] [but she didn’t stay long].’; ‘[Kim is an actor], [Pat is a teacher], [and Sam is an architect].’ Australian Curriculum English Glossary

First introduced in Australian Curriculum English Year 2: Understand that simple connections can be made between ideas by using a compound sentence with two or more clauses usually linked by a coordinating conjunction

(ACELA1467) (EN1-9B)

Complex sentence: has one or more subordinate clauses. In the following examples, the subordinate clauses are indicated by square brackets: ‘I took my umbrella [because it was raining].’; ‘[Because I am reading Shakespeare], my time is limited.’; ‘The man [who came to dinner] is my brother.’ Australian Curriculum English Glossary

Australian Curriculum English Year 5: Understand the difference between main and subordinate clauses and that a complex sentence involves at least one subordinate clause.

(ACELA1507) (EN3-6B)

Some students may benefit from understanding and identifying coordinating conjunctions (compound sentences) and subordinating conjunctions.

The article, Get with the Beat: Sentence Rhythm, may be useful and identifies how and why sentence structures and rhythms are significant in writing and reading, including the role of long and short sentences; the impact of genre; the use of fragments; and the importance of practising. There is also a range of examples.

It is important to understand sentence structures in order to explore the rhythm and pace of prose. This includes what the author is communicating to the reader as the more complex, repetitive or continuous aspects of events or lives, and what the author wants to emphasise as significant, sudden or disruptive details.

Revisiting narrative point of view

This includes the various ways in which a narrator may be related to the story. For example, the narrator might take the role of first or third person, omniscient or restricted in their knowledge of events, as reliable or unreliable in interpretation of what happens. (Australian Curriculum Glossary)

English, Year 5: Recognise that ideas in literary texts can be conveyed from different viewpoints, which can lead to different kinds of interpretations and responses.

(ACELT1610) (EN3-8D)

In the case of The Children’s Bach, Garner uses third-person omniscient point of view:Third person omniscient is a method of storytelling in which the narrator knows the thoughts and feelings of all of the characters in the story, as opposed to third person limited, which adheres closely to one character’s perspective. Through third person omniscient, a writer may bring to life an entire world of characters. From About.com fiction writing.

Narrative point of view is significant because it positions the reader within/beyond the characters and events. For example, if links are made to Carry Me Down by M. J. Hyland, students will be aware that the narrative point in that text is very different from The Children’s Bach. In the former, John Egan tells the story as an unreliable narrator. We see everything through his eyes without any reliable glimpse of the perspectives of the other characters. Whilst in The Children’s Bach, Garner shifts perspective and provides insights and internal monologue for each of the main characters so that we might better understand multiple perspectives on the complexity of relationships and events and as they unfold.

Activity 3: Close study

Sentence structure, rhythm, meaning and identification of point of view

In this activity, students analyse Extracts A–D.

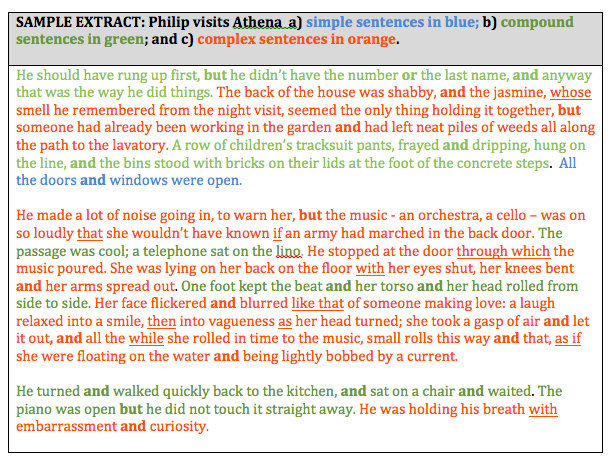

- Identify and distinguish between simple, compound and complex sentences using the colour code suggested.

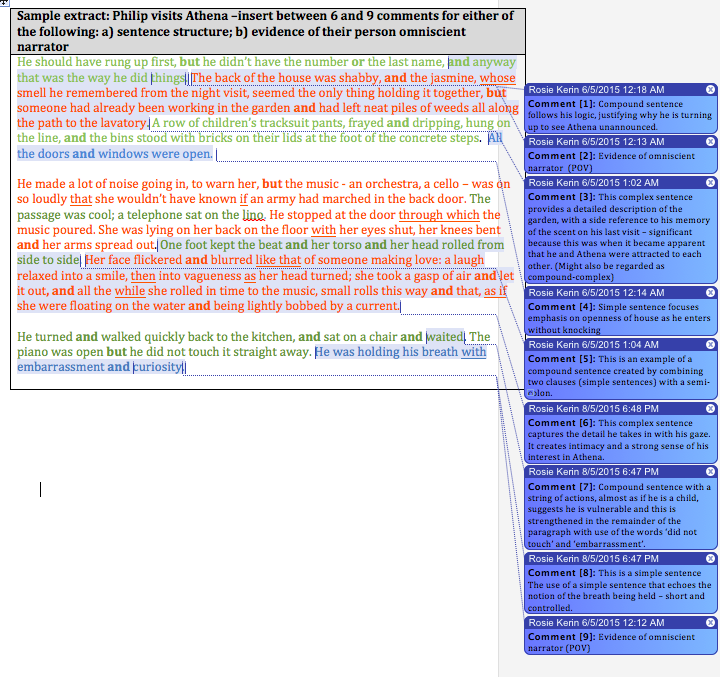

- Make between six and nine analytical/evaluative comments regarding the use of sentence structures and the third person omniscient point of view, using Word’s Track Changes feature.

If students are unfamiliar with Track Changes they should consult either of these two resources: Track changes while you work or wikihow: How to add annotations in Word.

To support students with this task, the following sample extracts are provided. The first illustrates the identification of sentence structures, whilst the second provides an example of analytic/evaluative comments on the text using Track Changes.

(ACELR023) (ACELR027) (ACELR029) (ACELR031)

Sample extract

|

|

Instructions and extracts A–D (PDF, 468KB)

Activity 4: Personal experiences, diary writing and the creation of characters

Introduction to the activity

Helen Garner is known for her extensive use of note taking and journal/diary writing as the basis for both her fiction and non-fiction works. She records her impressions and observations of ordinary daily life, her experiences and interactions with others, including family, friends and people she doesn’t know. From these observations and recordings Garner’s stories and characters emerge.

I get out that diary at the end of the day, and without fail I write ‘Today I saw so-and-so, she struck me as this. This is what she was wearing. I didn’t like her. I thought she was bullshitting me.’

And I’m writing this for my own purposes. I write in the most vivid possible way how the person struck me. So I’ve got a detailed account not just of what they said to me in answer to my questions, but a writerly account of that person’s demeanour with me, whether I trusted her or not, whether I thought she had some kind of agenda, or if she was suffering from some emotion that she couldn’t articulate. It is the most fantastic material because it’s hot.’

From Truth, Memories: Words with Helen Garner

. . . and

During the four years between Honour and Other People’s Children and The Children’s Bach I kept a notebook. I blindly took notes. I didn’t know what it was for or what I was going to do with it. Then when I got a grant I took out the notebooks and typed them up. It was completely random note-taking. I had no characters in mind. I noticed there were themes running through the notes that I didn’t know were there when I was taking them. It took me six months to work out what I was going to do with it. When I worked out the characters I realised the notes might apply to situations these characters could be put in. What I’m saying is I didn’t know I was working when in fact I was working. I had to nut out ways to stitch them together.

From Going Down Swinging: An interview with Helen Garner

This aspect of Garner’s writing has been praised, criticised and hotly debated. The authenticity of her writing in Monkey Grip was questioned: “Had she simply copied her diaries, rather than written a novel in the ‘right’ way?” The Australian November 2012. In her article: ‘I‘ published in the literary journal, Meanjin, Garner has defended herself:

Shouldn’t a real writer be writing about something other than herself and her immediate circle? I’ve been haunted by this question since 1977 when a reviewer of Monkey Grip asked irritably what the fuss was about: as far as he could see, all I’d done was publish my diaries. I went round for years after that in a lather of defensiveness: “It’s a novel, thank you very much.” But I’m too old to bother with that crap any more. I might as well come clean. I did publish my diary. That’s exactly what I did. I left out what I thought were the boring bits, wrote bridging passages, and changed all the names.

Personal experiences, diary writing and the creation of characters

Students will complete Parts A and B

Part A: Analysing the text and identifying possible journal notes and observations by Garner. Select a passage of between two and three hundred words from the novel. Type it up in Word and then Track Changes to identify three distinct sentences or clauses, and insert one comment for each of these, indicating why you believe that sentence or clause probably is (or probably is not) based on real-life observations.

Part B: Using and integrating the journal writing process.

- Select a person students know and observe that individual for a period of one week, taking note of behaviour, speech, physicality, personality and experiences. Students must ensure their notes do not in any way cause offence, humiliation, intimidation or ridicule, or invade someone’s privacy.

- Create a character based on these notes where some aspects of the observed person are recognisable and some are not.

- Write the opening paragraph of a narrative with this character as the central figure.

- Use a mixture of simple, compound, and complex sentences as explored in Activity 3 (PDF, 468KB) paying close attention to selection, placement and effect.

- Use the Track Changes tool to annotate the paragraph showing:

- aspects of character drawn directly from their notes/observations that are demonstrably accurate;

- aspects drawn that are fictional;

- one of each sentence types (simple, compound or complex) and the structural/creative reason for the selection (rhythm, impact etc.).

- The prose passage (not including tracked changes) should be between 175 and 225 words.

(ACELR019) (ACELR033) (ACELR034)

Activity 5: Characterisation in The Children’s Bach

This activity replicates Activity 7 in the unit on Carry Me Down by M. J. Hyland.

One way of analysing a text is to engage in comparative character analysis. In this activity students will examine the text, identifying data upon which they can make claims about the characters and themes of the novel.

- Divide the class into four groups (or eight according to the size and nature of your class) so that each group takes responsibility for the analysis of one of the central characters. You may wish to combine Billy, Arthur and Poppy, given their lesser roles.

- Groups will complete the table below with textual evidence in relation to their selected character, and then complete via a jigsaw activity or an electronic publication as a means of sharing. This will be particularly useful for Assessment Tasks 2 and 3.

TABLE: Activity 5

| Textual evidence revealing something significant about character (Ensure evidence is selected across the entire novel.) | Character’s name: |

| FOUR key pieces of dialogue spoken by or about that character. | |

| FOUR key phrases used to show their full body movement/actions (physicality). | |

| FOUR key phrases used to show their facial movements in speech or eating. | |

| FIVE key adjectives or adverbs relating to what a character likes to wear, what they read, what they eat, what they enjoy doing. | |

| THREE words to describe the character’s relationship to the other central characters. | Dexter: Athena: Elizabeth: Vicki: Philip: Poppy: Billy: Arthur: |

| How is this character significant to the narrative and themes in the novel? | |

| What are your feelings toward this character? Are you empathetic, critical or indifferent? Explain with reference to textual evidence collected in this table. |

Introduction

According to Australian academic and critic Don Anderson, ‘There are four perfect short novels in the English language. They are, in chronological order, Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier, Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises and Garner’s The Children’s Bach.’ Wikipedia.

Although Garner’s novel was welcomed after the success and promise of Monkey Grip, and reviewed favourably, this praise exceeds most other commentaries at the time and since. While it won the South Australian Premier’s Awards in 1986, and was the basis of a chamber opera in 2008, it is not the most enduring of Garner’s work. Her more recent forays into court and crime reporting have generated stronger media interest and sales. For example, The First Stone (1995), Joe Cinque’s Consolation (2004) and This House of Grief (2014) have been the source of considerable debate and interest in literary and journalistic circles.

The Children’s Bach, like much of Garner’s work, captures in close detail the lives of ordinary Australians. In her fiction, these lives remain located in the domestic settings of suburban Melbourne, (while in her non-fiction, the lives of ordinary Australians become propelled into the legal/criminal sphere). Whilst the homes, courts and a university college are located firmly in Australia, the themes she explores are universal and cross national and many cultural boundaries.

Activity 6: Universal themes

While the novel is set within the parameters of inner-Northern Melbourne, and places are named, this does not limit the resonance of themes and characters with readers who live in other parts of Australia or the world, nor to those of us looking back on the text, 30 years after it was written.

Themes such as family tension, living with a disabled child in the family, sibling estrangement, infidelity and feminism might be located within the reality of our lives or neighbourhoods. However, we can also learn and recognise themes when reading literature that is situated in unfamiliar worlds in the present, past or future.

Step 1: The students’ task, in groups, is to find themes in the novel, The Children’s Bach, that they believe endure across time and place. Students should identify four key themes from the list below as well as others that are believed to be as relevant to their grandparents when they were growing, as they are to young adults today, or to those who live on other continents in very different contexts.

- Domestic life

- Feminism

- Women and work (consider these statistics regarding changing times)

- Raising a disabled child

- Sibling relationships

- Infidelity

- Death of a parent

- Living in a city

- Pop culture

Step 2: The next step is to identify a theme or preoccupation of Helen Garner’s, evident in The Children’s Bach that is seen to be universal (across time and place). Students are to justify their thinking by providing a passage or quotes from the novel (between 50–100 words total) and at least two URLs to contemporary online resources or media relating to that theme. Further, they are to explain why they believe this theme is universal (between 100–150 words).

Step 3: Discuss the relevance and/or irrelevance of The Children’s Bach to contemporary Australian school students (between 100–150 words).

Assessment task 1: (Receptive)

Create a domestic scene on the verge of disruption

(This assessment task is a version of Assessment task 1 in the unit on Carry Me Down by M. J. Hyland, though this task addresses AC: Literature – Unit 2, rather than Unit 1.)

Students are to select any ONE of the images below of families and construct a scene in 750–1000 words that:

- includes universal themes (see Activity 6);

- includes the arrival of a long-lost family member or friend who is not yet visible in the photograph, but how in some way unsettles the scene, hinting that this may lead to disruption of family life later in the narrative;

- includes consciously constructed sentence structure (see Activity 3);

- includes a clearly developed point of view: omniscient or first person perspective (see Activity 3);

- avoids stereotypes, allowing for some doubt, irony or even humour, to create characters and the scene;

- follows the conventions used by Helen Garner to indicate dialogue (this includes indentation and punctuation);

- addresses each aspect of the rubric (PDF, 229KB) which stresses the importance of abiding by word limits.

Students select a photograph from the table below, considering the point of view they will adopt. Focus on a minimum of two and a maximum of four characters, including the unseen character who will enter the scene. There is no definite order for the following questions which students should consider as they plan and explore the possibilities of their scene:

- What makes this family vulnerable/interesting/unique?

- Who are each of the characters and what makes them distinctive within the family?

- How are they related, and what are the distinguishing features of their relationships?

- What is the context – time, place, social, political and economic circumstances?

- What history of tensions, goodwill, happiness, insecurity and/or events influence or surface in the present moment?

- What can you include to mimic Garner’s focus on the details of domestic life?

- What style of language and vocabulary (including slang) will be used to enliven the dialogue and help the reader learn more about what distinguishes each character?

- How will the scene open, develop into a revelation of some kind and then close with a degree of ambiguity about how the disruption might undo the family for a time, if not forever?

Creating a domestic scene on the verge of disruption

Before commencing this 750–1,000 word task as outlined and prompted above, students should consult the assessment rubric (PDF, 229KB) provided for it.

1. Photo by Kevin Dooley. |

2. From Amandajm. |

3. Photo by Thomas Hawk. |

4. Photo by Trent Kelley. |

5. From macinate. |

6. From Wonderlane. |

7. Photo by Stefan Schmitz. |

8. From Nordiska museet. |

9. Photo by Colin Campbell. |

10. From Bread for the World. |

11. From Apple Jia. |

12. From Taz. |

Please note that this assessment task is a version of the Assessment Task 1 in the unit on Carry Me Down by Helen Garner.

Synthesising ideas

One of Garner’s fans reflected on her reading of Monkey Grip as a young woman, and then more recently many years later:

Garner’s writing is a place in itself. It is the words and everything else in between. It is her honesty and her humanity. She helps us enter places we think we already know, only leading us in through a different door. In my 20s, I used to think that experience happened elsewhere, that reading about ordinary Australians would not be worth reading.

From The Age, Revisiting Chapters from the Heart.

Although Garner has crossed boundaries between fiction, non-fiction, short stories and journalism, she is highly regarded by critics for ‘her honesty and her humanity’.

Further to this, another critic, in reviewing Garner’s 2014 best-seller, This House of Grief, commented:

This House of Grief has all the trademark Helen Garner touches: harrowing scenes recorded without restraint or censorship; touching observations of characters’ weaknesses; wry moments of humour.

From The Guardian Review.

This capacity to record life in its various and conflicting wry, harrowing and humane moments is hallmark Garner. Robert Dessaix echoes this in a review of The Spare Room (2008) when he suggests that Garner is unique in her capacity to ‘report from the suburban front line’ with ‘abrupt insights and kitchen-table candour’.

Building on these insights, students should consider the materials provided that feature extracts from Garner’s work (PDF, 116KB). Each of the extracts illustrates aspects of Garner’s style and preoccupations, and students can draw on these in their response to Assessment task 2 (PDF, 238KB).

Assessment Task 2 (Receptive): Formal literary essay

‘Helen Garner creates family relationships and homes that appear mundane, yet under the surface ripples begin to emerge suggesting that those characters are lurching toward pain or regret.’

Discuss this statement, drawing on your knowledge and understanding of The Children’s Bach, as well as the extracts from other works by Helen Garner (PDF, 116KB).

The assessment rubric (PDF, 238KB) should be consulted before commencing the essay, ensuring criteria are addressed and word limits observed.

(ACELR020) (ACELR022) (ACELR023) (ACELR029) (ACELR030) (ACELR031) (ACELR036)

Composite assessment task (Receptive and Productive): Formal literary essay

The Children’s Bach by Helen Garner and Carry Me Down by M. J. Hyland

Please note that this task addresses Learning Outcomes and Content Descriptors for Senior Secondary Literature – Unit 2, though it might easily be adapted to current local needs and syllabuses. The assessment rubric (PDF, 233KB) should be consulted before commencing the essay, ensuring criteria for Unit 2 are addressed and word limits observed.

This Kakfa quote, ‘A book must be an ice axe to break the sea frozen inside us,’ has been used in reference to both Garner’s and Hyland’s fiction.

With close reference to The Children’s Bach and Carry Me Down, discuss how both authors construct domestic spaces and disruptions where ‘ice axes’ break the ‘sea frozen’ within central characters. Your essay must be between 750 and 1,000 words.