NOTE: In David Griffin’s version of The Happiness Box, Wobbley the frog’s name is spelled with an ‘e’. In Mark Greenwood’s version, his name is spelled without an ‘e’. This unit uses both spellings according to whichever version of the text is being referenced.

Connecting to prior knowledge

NOTE: Please be sensitive to any students who may have experienced conflict, have family members serving overseas in war zones or feel sadness triggered by the topic. Adjust activities accordingly and encourage concerned students to talk privately to the teacher or a trusted adult if support is needed.

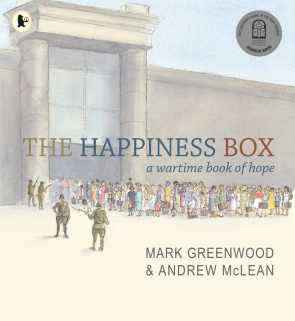

The Happiness Box: A Wartime Book of Hope, by Mark Greenwood and Andrew McLean, offers opportunities for many different conversations ranging from aspects of war to hope and happiness.

Begin by showing students the cover without comment, except to read the title and author. Students should notice the crowd outside the huge gate. Prompt them to look closely, as you want them to notice who is in the crowd, their attire and any other items, as well as the soldiers and guns.

Turn the book over and read the blurb.

Now, in pairs, invite students to talk about what they have seen and heard. Combine pairs to form groups of four and share further. Come back as a whole class and invite comments and wonderings. If students have questions, record these to return to later. Focus the conversation on the last sentence in the blurb: “the inspirational true story of a book that became a National Treasure.”

Discuss to ensure that students understand the statement, the meaning of “inspirational” and the concept of a national treasure. Explore the morphemes in “inspirational” (“inspire” as root word, suffix “tion” as the “state of being” and suffix “al” as “having the character of”). Discuss the origins of the root word “inspire” (Latin, meaning to “inflame”).

Have students form groups of four to share stories about something they think is inspirational. Provide some ideas to get started, such as a student or ex-student from the school, a family member or someone local who has done something that might be considered inspirational. Record ideas.

Now shift the conversation to the idea of a national treasure. Are students aware of anything or anyone that has been identified as a national treasure? It might be a person, a place such as the Great Barrier Reef or a thing. National living treasures can be found here but it is more likely that students will suggest someone local. Record ideas.

Move around the groups, identify one or two ideas from each, and invite those groups to share their ideas with the whole class.

Exploring the text in context of our community, school and “me”

Ask if any students know of a family member who served in World War II. In 2020 there were only 12,000 living returned veterans from WWII, all in their nineties. It may be possible to identify the family of someone local around Anzac Day, when tributes are made to those that served in the wars (a local RSL may be able to assist). Check if there is a local memorial to those that served in the war; if it is nearby you may be able to do a class visit, or you can search online through the National Register of War Memorials. The website refers to these places as “Places of Pride”. Discuss what this might mean.

Provide time for family members or local residents to talk to the class, briefing them on the information relevant to WWII and your context. Try to identify someone with links to the war in South East Asia during WWII, as that is the context for this text. WWII is not part of the curriculum for Year 4 but a short history will give context for the story. Links to various sources of information can be found under More Resources.

NOTE: If you consider it appropriate, a short history of the Battle of Singapore would help students understand the setting of The Happiness Box. Some students may know about the war from relatives. Give these students an opportunity to share what they know; it may be participating in Anzac Day in their local area or watching the Anzac Day March on TV.

Australia’s involvement in WWII was announced by Prime Minister Robert Gordon Menzies on 3 September 1939. Initially the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) joined the war in June 1940, the Army headed to the Mediterranean and North Africa in 1941, and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) played a part in the Battle of Britain. The war lasted from 1939 to 1945 and almost one million Australian men and women served during that time.

It is well known that Australians served overseas in places like Germany and Italy in Europe, the Mediterranean and North Africa, but many also served in Asia. It was always thought that Britain would protect Singapore, but in the end it was the Australians who played a significant role in Singapore and Malaya. In February 1941 nearly 6,000 Australian troops arrived in Singapore on the Queen Mary, which had been transformed into a troop ship the year before in the Singapore Naval Base.

There were two major battles: one between 18–23 January 1942, over just six days, and one between 1–15 February 1942, over fourteen days. The latter was the Battle of Singapore referred to in the opening pages of The Happiness Box. Many Australians and other members of the Allied forces lost their lives in these two battles.

On 15 February the Allied forces surrendered to the Japanese. Many soldiers and civilians then became prisoners of war and were sent to Changi Prison, which is the setting for this book. There were many English boys and girls among the civilians held in Changi and nearby prisons.

By the end of the war 39,000 Australians had lost their lives. On 17 February all of the 50,000 British, Australian and local volunteer forces were moved by route march to Changi. The Japanese agreed to some trucks for the wounded and to carry the ten days’ worth of rations each man was ordered to take. Many who were held captive by the Germans in Europe came home, but of those captured by the Japanese in places like Changi, about 36% died in captivity due to torture and conditions.

Now turn to the pages at the back of the book and read the information about Sir David Griffin CBE (1915–2004) and Captain Herbert Leslie Greener (1900–1974). Also read the section at the bottom of the page about Changi. Return to the cover where students can see the soldiers and civilians, including women and children, under guard about to enter the camp. Take a moment for students to understand the number given – 20,000 Allied troops and civilians were imprisoned in Changi Prison and the Selarang Barracks. You might like to do that by working out how many schools your size that would be.

Finally, locate Singapore on a map in relation to Australia and Great Britain. Singapore was a British territory and Australia was defending the island for Britain. Note the distance to Australia. Tell students that it was critical to protect Singapore to prevent the Japanese coming south. After surrender, the Japanese did come south. Four days after surrender, on 19 February 1942, the first Japanese bombs were dropped on Darwin. This resulted in 243 people killed, nearly 400 wounded, 20 aircraft destroyed, 8 ships sunk and military facilities destroyed. The air attacks continued until November 1943, over which time Darwin was bombed 64 times. Bombs were also dropped on Townsville, Katherine, Wyndham, Derby, Broome and Port Headland. Additionally, on 31 March 1942 three Japanese submarines attacked Sydney Harbour, killing 21 sailors. The Japanese attacks continued until June 1943, claiming a total of 503 lives.

Even snippets of this information provide a sombre introduction to this book, so remind students of the title: it is a book of hope. Brainstorm what that means.

- What type of things might the prisoners have hoped for?

- What type of things do we all hope for?

- When is it important to have hope?

Rich assessment task

The Allied forces were made up of men and women from Australia, India, Britain and China; Singapore was, and still is, a very multicultural society.

Ask students to look again at the cover. Explain that the assessment task is to choose someone from the mass of people outside the jail: a man, a woman or a child. All of these people were in Singapore at the time of surrender and immediately became prisoners of war.

The task is to write in character as the person chosen – for example, as the lady in the yellow hat carrying a small suitcase. Tell students that they are to think about the vocabulary they use. They can draw from the discussions thus far.

Once students have chosen who they will be, invite them to wander the room. On your signal, they will stop and face another student. You ask: “Who are you?” Each student responds in character, speaking to their partner. On your call, they will wander again and stop on a signal to find another partner. You ask: “How did you get here?”

Continue the process with the questions: “What have you brought with you?” and “What are you thinking?”

Now, working individually, students will write a short piece in character. Prompt with the following questions:

- Who are you?

- How are you feeling standing in the line?

- What are you thinking?

- What have you brought with you?

- How did you get here?

- Are you alone? If not, who are you with?

- Who was left behind?

- What do you think might happen?

- What do you hope for?

After the set time, students will form pairs to read their writing to a partner. After a brief discussion of both pieces, they will return to their own writing to edit for meaning, add detail, etc. While this is a short piece of writing, it is important that the writer shows they have thought about the person and that the feelings and descriptions are consistent.

Responding to the text

Read The Happiness Box to the class. After reading, ask students to take a moment to reflect before writing a response in their reading journals. Then, in small groups, invite them to share their responses. As a whole class, record some of the responses from those who want to share.

Now read the section on the last page about the original book that was buried in the camp. Display the images of the book available from the State Library of NSW.

Before moving on, show students the last double page spread in The Happiness Box and revisit the ideas from the earlier discussion about national treasures. Why might this small book be a national treasure?

Return to the full title – The Happiness Box: A Wartime Book of Hope. Ask students what the opposite of “hope” might be. Record the answers; suggest that “despair” or “fear” may be possibilities.

Organise students into groups of four or five with a copy of the book. Ask half of the groups to note all the places in the book where “despair” might have been present, recording any words that support their choice. This activity focuses on the words of the text. Ask the remaining groups do the same thing for “hope”.

| Despair | Hope |

| Pages 1 and 2

He felt a jolt with each bursting shell. |

Page 10

In stories he found escape from the miserable conditions |

| Pages 3 and 4

soldiers swarmed the streets waving bayonets |

Page 11

we could make presents (for children) |

| Pages 5 and 6

a grim fortress appeared before them |

Page 14

Page by page, Griff wove into words the tale of Winston the lizard, Martin the monkey and Wobbly the frog. |

|

|

|

Display the responses. Ask students if they can find an example where both despair and hope might have been present together.

If time allows, read The Treasure Box* by Margaret Wild and Freya Blackwood (also available as a video on StoryBox Hub). Extend the previous conversation about despair and hope – both are also evident in this book. Allow time for students to compare and contrast the way these elements are included.

Guide the students to see that although these two stories are set in different parts of the world, they have one common element. Ask what that might be. They may suggest that the answer is the value of a book.

* Reading Australia title

Exploring plot, character, setting and theme

As a class, list the settings in the book from the first pages of the battle to the end of the war. Clues about the details of each setting can be found in the illustrations as well as the text.

| Page | What the text tells me | What the illustrations tell me | Setting |

| Pages 1–2 | there was a battle | the men were frightened | battlefield |

| Pages 3–4 | the Allies surrendered | the men were captured by the Japanese soldiers | Singapore City |

| Pages 5–6 | many were taken to Changi Prison | there were crowds of people of all ages | prison |

| Pages 7–8 | the camp was crowded and there was not much food | the men were not getting enough to eat | prison |

| Pages 9–10 | the men played games and sang | reading made their lives brighter | prison |

Discuss plot in a story. Quickly record what the students know about plot and the elements that contribute to it.

This book has some highs and lows that students would recognise are connected to the setting. Now they will look at the plot and how the conflict was or was not resolved. Provide time back in groups with a copy of the book to discuss.

In groups, ask students to track the plot throughout the book. Once a discussion has taken place, construct a book plot profile together as a class. Details can be found here.

Decide on a starting point. On the first pages there is a battle, followed by surrender, entering the prison, life in prison, making gifts, etc.

- What were the major events?

- Where does the story peak? Does it peak more than once? Is there a climax?

- Is there a resolution?

Prompt students to think about how the text and illustrations work together to achieve these things.

The discussion can be recorded on a whiteboard or using a plot diagram (Flash Player required).

Rich assessment task

Part of the assessment involves the teacher listening into the group and whole class discussions. The teacher should note which students read deeply and think analytically about the events taking place. Students have been exposed to the idea of war, but the experience of young people in WWII may be challenging for many to understand.

Ask students to think about the previous discussions and, using those discussions and the book, write a brief description of Griff and what type of person they think he is.

- What attributes does Griff have?

- What proof can be found in the text (words and illustrations) to support this view?

Examining text structure and organisation

Re-read the book while students relax with their eyes closed, listening to the words. After reading ask students to share what they were feeling and what they were “seeing”.

Now read again, focusing on the illustrations. Together identify that the illustrator, Andrew McLean, used pen and watercolour pastel.

Focus on the colours as you turn the pages. Students will notice the browns and greys in the opening pages and in the camp. What happens on pages 9 and 10, which show the prisoners playing a ball game, the concert and the men reading?

Continue through the book, noting the colour palette and change in colour when the situation changes.

Put students in groups with copies of the book to look for details in the illustrations. For example, on the page showing the concert the men are holding cards. What do they say? What is the message on the stage? On the page where the camp is liberated, what flags are flying?

Ask each group to report back on their findings, encouraging them to focus on the style of the illustrations and what they bring to the text.

Sticky-note storm the question: What technique does the illustrator use to add detail to this text?

Give students a moment to think about the question. They should write their idea(s) on a sticky-note and place it in the middle of the table (one idea per note). Review the ideas.

Examining grammar and vocabulary

Begin by exploring some of the vocabulary used in this book. Earlier on the class explored the word “inspirational”, including looking at morphemes and suffixes, and origins of root words. Review the responses and see if there are any further insights into the meaning of the word now that the book has been discussed more deeply.

Read the book again, stopping to record the following words. This way the students can think about not only the highlighted word, but the context in which the word is used. Add any other words students identify as challenging.

| Page | Word |

| Page 1 | stutter of gunfire |

| Page 5 | a grim fortress |

| Page 5 | guards barked instructions |

| Page 7 | men were interned |

| Page 8 | disease flourished |

| Page 10 | cooped up |

| Page 14 | scoured the barracks |

| Page 18 | aroused suspicion |

| Page 21 | shrunken by starvation |

| Page 24 | the liberation |

Give each group three of the words. Through discussion, each group should complete the chart below for their words.

| Word and context | Our agreed meaning | Dictionary meaning | Our sentence using the word |

| Supplies dwindled | the food became less and less | to diminish in size and amount | During the school holidays the traffic dwindled so it was faster to get to work. |

Share responses with the class. Allow discussion if class members have questions or need clarification.

Pronouns and connectives

The following activities reinforce how texts are made cohesive through pronoun references.

Griff scoured the barracks for spare paper. He couldn’t make wooden toys, but he could write a story.

Working as a class, identify the pronouns. Once students confirm that “he” replaces the name “Griff”, read the sentence substituting with the name, then with the pronoun. What changes? Discuss.

Then, in small groups, invite students to do the same thing with the sentences below. Provide copies of the book as students may discover that they need to return to the text to confirm the pronoun reference.

Captain Greener was an artist. He set to work bringing the characters to life with colour collected from flowers, leaves and clay.

Griff braced himself for a beating, but a mate sprang to his defence. “I’ll see it’s destroyed,” he promised.

Discuss how understanding the pronoun reference helps comprehension of the text.

Focus on “himself” (refers to Griff), “his” (possessive pronoun refers to Griff’s defence), “I” (the mate talking about himself), “it” (refers to the book) and “he” (the mate talking).

Then, using the sentence below, identify the connectives used.

After liberation, Griff’s mates returned to the barrack’s garden and dug up a box. Inside was a handmade book. The print was smudged, the colour was faded, but the Happiness Box had survived.

On the board, rewrite the sentence without the connectives:

After liberation, Griff’s mates returned to the barrack’s garden. They dug up a box. Inside was a handmade book. The print was smudged. The colour was faded. The Happiness Box had survived.

In the first instance a pronoun is needed to connect the sentences in a different way to the conjunction. Is one technique better?

Discuss the last sentence. Does the meaning change? Read both versions aloud and discuss. Allow time for students to explore the text and find other examples of pronouns and connectives (linking devices) that make the text cohesive.

Now that students have a better understanding of how the writer used pronoun references, ask them to return to and find examples in some of their own recent writing.

Rich assessment task

After completing the activities, finish by asking students to record:

- 3 things that they have learnt

- 2 questions they have

- 1 thing that surprised them

Now, in groups of four, compare and discuss learnings, questions and surprises.

Take time to respond to the outstanding questions through a shared discussion. Celebrate the learnings.

Students have learnt that The Happiness Box by David Griffin, with drawings by Leslie Greener, was the book behind the book they have been reading. After the original book was retrieved from its hiding place following the war, it was eventually printed and sold in 1991. The history of this little book is:

- Written in Changi in December 1942

- Buried in Changi Prison before Christmas 1942

- Dug up from its secret hiding place after the liberation of Singapore on 5 September 1945

- Published in Singapore in 1991

The original version of The Happiness Box toured Australia, along with Sir Don Bradman’s cricket bat and Ned Kelly’s helmet, as part of the National Treasures exhibition from Australia’s libraries. The book is now in the State Library of NSW.

As a class, return to the earlier discussion on national treasures. What do the items that toured have in common? Why would this small book be considered a national treasure?

The recovered book was dedicated: “To the children whose fathers went to Singapore and never came back” (page 3, 1991). Briefly discuss the dedication.

The book told the story of three friends: Winston, a chi chak (lizard); Martin, a monkey; and Wobbley, a frog. They showed great kindness to the jungle creatures and were very happy in their small house in the jungle. One day Wobbley found an old heavy box when he was digging in his rice field. The friends were afraid to open it and went off to ask the wisest creatures in the jungle what to do. After visiting many animals, they asked Bumble Bee. After much consideration, he told the friends to go home and open the box, “for in it you will find the happiness of the world” (page 23, 1991).

Invite students to work in groups of four or five to discuss what the three friends might have found in the box. Each group is to plan how to present their idea to the class. It can be done as an oral presentation, a short play, a PowerPoint, etc. Check in with each group to ensure that they understand any time limits you need to impose.

Return as a class to share the ideas from the last activity. Now explain that when the friends opened the box it was lined with blue velvet and contained three books: one for each of the friends. Printed in gold was a message: “In these three books there lies the secret to happiness. Read them; then go out into the world and teach your fellow creatures how to be happy” (page 28, 1991).

Re-form the groups and allow the students to think about their response to the first task. Now they can add to or change what they did and decide on three things that they might do to teach others how to be happy. Display, share and celebrate the ideas.

In 2018 the Sydney Symphony Orchestra put this story to music, describing it as an inspiring tale of friendship and courage. The music was composed by Bryony Marks. It is no longer available in full, so listen to the introduction on YouTube. This clip introduces the instruments that represent the different characters. The choice of instruments gives insight into each of their natures. You might like to show images of the original book available in the State Library of NSW collection while listening.

Provide time for students to discuss what they have heard and seen. Ask if the introduction to the performance offered any clues as to what the secret of happiness might be.

Now reveal the secrets found in the old book:

- Winston’s book: “My book says that the world will be happy if people learn to be clever and if they learn to be like Martin and Wobbley” (page 29, 1991).

- Wobbley’s book: “My book says that the world will be happy if people work hard and if they learn to be like Martin and Winston” (page 30, 1991).

- Martin’s book: “My book says that the world will be happy if people are generous and kind and if they learn to be like Winston and Old Wobbley” (page 30, 1991).

The three friends decided that, together, those things meant that they must go out into the world and teach their neighbours how to be clever, industrious and kind so that their neighbours could be as happy as they were.

The task now is for students to individually write what they think is the secret to happiness. It may be a version of one of the things revealed in the book, or something completely different. Before writing, allow some discussion time as a class. Prompt with the questions:

- Are all three of the things from the book important?

- Is one more important that the others?

- Is there something more important that could be the secret to happiness?

- This book was written in 1942 during a war. Do you think the secret to happiness might have changed since then?

Invite students to create posters with their ideas so that the “secrets of happiness” can be displayed around the school. Encourage other students to read them and talk about all the ideas for happiness. Invite parents and guardians to come to the school so that the class can take them on a guided “happiness” tour of what happiness means to Year 4.

(AC9E4LE05) (AC9E4LY05) (AC9E4LY06)

Rich assessment task

Read the section on the last page of Mark Greenwood and Andrew McLean’s The Happiness Box. In the third paragraph, it says that the book was written to chase away fear and give hope:

The secrets to happiness hidden in the story were virtues such as the importance of friendship, kindness, compassion, generosity, loyalty, faith, courage and hard work. The author hoped children would find these secrets hidden in the story.

Invite small groups of students to find a place around the classroom and call out one of the secrets, such as “compassion”. After a couple of minutes discussing the virtue, each group organises itself into a shape to represent that word. The teacher can photograph the representations before continuing with the other words.

Display some of the images taken and discuss as a class. This process will give each student a better understanding of each of the words.

Finally, ask each student to choose one of the words and write about that word and what it might look like on a daily basis. Encourage students to use text and images to present their idea. Both text and image should fit on one A4 page.

Publish the pages, with the audience being students in the class. Display them or make them into a book for the class library. Refer to the words regularly to build up an understanding of the virtues.

Optional assessment task

Author Mark Greenwood has generously provided a copy of the speech he gave (PDF, 102KB) when The Happiness Box was launched in Singapore in 2018.

Read the speech to the class as you might deliver it at a launch (that is, stand and give the air of formality as you recite it). Provide copies for students if they wish to read it independently.

Put students in six small groups, providing each with a copy of the speech and a task (two groups will do Task 1, two will do Task 2 and two will do Task 3). Let the students know the time limit to complete the first task (20 minutes).

After the time is up, put the two groups with the same task together to compare and contrast their ideas (10 minutes).

Task 1

- What new information have you learned from Mark Greenwood’s speech?

- What does the speech tell you about Mark Greenwood as a person and a writer?

Task 2

Re-read paragraph four:

I first saw the original Happiness Box book in a touring exhibition of National Treasures from Australia’s Great Libraries. It showed that books and reading, knowledge and education can also be a secret to happiness.

- Mark Greenwood reveals another secret to happiness; what is it?

- Do you agree that reading, knowledge and education may also be secrets to happiness?

- If so, how might you share this “secret” with other students in the school?

Task 3

Re-read what Mark Greenwood says about Griff:

Within its walls of a prison, with a book in hand, his thoughts were free. He studied the characters in books. He stored their voices in his heart and wove them into his own words.

- Explain what you think this means.

- How might this have helped Griff (and others) survive the terrible conditions in Changi prison?

Conclude by inviting students from each group to discuss their assigned tasks. Encourage them to comment on any differences between the groups with like tasks.