Introductory activities

Group discussion

What is a short story?

Students should watch the video ‘Elements of the Short Story‘ by Clifton Fadiman, Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Ask the students:

- Do you read short stories?

- Share with the groups any short stories you have read and what you liked or didn’t like.

- Why would someone write short stories instead of novels?

- Why would someone read short stories instead of novels?

- What can you achieve in short stories that you can’t achieve in novels?

Student activity

Use Fadiman’s discussion to complete these sentences.

Fadiman thinks we love stories because: …………………………………………………………

The storyteller takes a chunk of life and: ……………………………………………..……………

Edgar Allan Poe says: …………………………………………………………………….……

Plot is: ……………………………………………………………………………………

Style is: ……………………………………………………………………

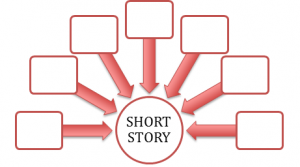

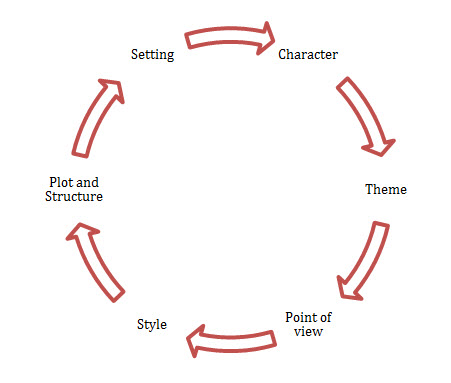

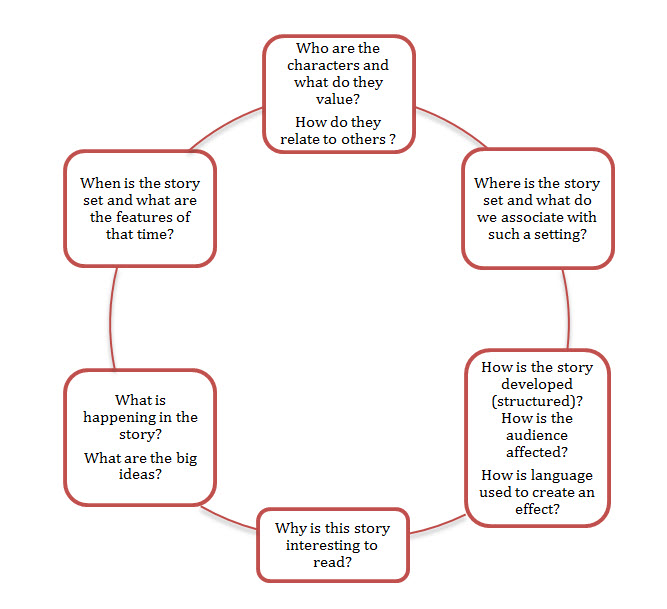

What are the seven elements of the short story that Fadiman lists? Add them to the diagram below. Make sure you know what each one means.

What do each of these ‘short stories’ below (presented by Fadiman) reveal about story?

- ‘In the room sat the last human being on earth. There was a knock on the door.’

- ‘The king died and then the queen died.’

- ‘The king died and then the queen died of grief.’

How has this discussion made you rethink the idea of short stories?

Initial composing: 50 word short stories

50 word short stories are a good way to stimulate creativity.

1. Read. There are many websites with 50 word stories. Students should read these to each other. Try this website.

2. Write. Students can create their own 50 word stories in groups or individually. The title can be included in the word count. Consider removing ‘the’ or ‘a’. Sentence fragments are acceptable. They can start by using the two stories Fadiman introduces and build these into 50 word stories:

- ‘In the room sat the last human being on earth. There was a knock on the door.’

- ‘The king died and then the queen died.’

3. Present. Readers Theatre: Present the stories to the class as performed readings.

4. Respond. Students are paired and focus on their partners’ presentations. They write one thing they liked and one thing that could be developed in the student’s work. This has to be expressed in positive terms. They share these with each other.

Initial response: Listening and reading

If an audio reading is not available then organise students into groups to read one of the shorter stories. Choose from these shorter stories: ‘Jacko’s Reach’, ‘The Empty Lunch-tin’, ‘Sorrows and Secrets’, ‘In Trust’, ‘The Only Speaker of His Tongue’, ‘The Sun in Winter’, ‘A Medium.’

- They should be given time for quiet reading or they can read aloud around their group.

- As a group students should select a passage that stands out for them.

- The group presents the passage to the class and explains why this passage was chosen and what it shows about the story.

- Use Fadiman’s discussion to consider the plot – does the plot satisfactorily answer the WHY of the story? (What is the motivation/purpose of the story?)

Researching the writer

- Students should find reviews from overseas papers and journals such as The Guardian, The New York Times or other significant journals and newspapers outside Australia. They should explore the question of: What is valued in Malouf’s writing?

- Students can also look at articles, videos and audio resources about David Malouf to see the respect he is given in the literary community. These could include:

David Malouf: my life as a writer

Conversations with David Malouf

How important are titles?

The activities in this section are designed to make students think about the relationship of the title to the story. How much information does the title yield?

Look at the headings of Malouf’s books of short stories and guess whether these stories will focus on place or character or idea.

- Every Move you Make

- Dream Stuff

- Antipodes

- Child’s Play

Structure of the collection

This collection of 31 stories from four books of stories appears in reverse chronological order from most recent to earliest work:

- Every Move you Make – 2006

- Dream Stuff – 2000

- Antipodes – 1985

- Child’s Play – 1982

The last two stories of the collection appeared with the novel Child’s Play, set in Italy and centred on an assassination. Like the novel they accompany, these stories are about violence and the effect on the public of violent acts. While the earlier stories are powerful, starting the book with the story ‘The Valley of Lagoons’ makes a clear statement that Malouf’s writing is continuing to engage audiences. This opening story is a sensitive evocation of a rural Australia seen through the eyes of a young boy at a stage of transition. A subtle and sensitive inclusion of Aboriginal connection to land shows how the political is ever-present in any personal experience that centres on a rural place in Australia.

The Complete Stories gives an overview of a distinguished career but also shows how strong Malouf’s voice was even in the early stories.

Because it is such a condensed form, the short story can be centred on character, ideas or mood. Short stories do not usually have event-filled plots or multiple points of view. In some stories the events are central (‘War Baby’, ‘A Traveller’s Tale’, ‘Great Day’, ‘The Prowler’); in other stories he focuses strongly on character (‘Mrs. Porter and the Rock’, ‘Sally’s Story’, ‘Southern Skies’); in other stories setting is the driving force (‘Jacko’s Reach’, ‘A Change of Scene’, ‘The Valley of Lagoons’) and other stories are formed around ideas (‘The Only Speaker of His Tongue’, ‘Jacko’s Reach’). And yet to isolate one element as being central loses the sense of how strongly integrated all the parts of the narrative are. Whatever the focus, all the elements add up to an intense mood where character, setting and event interact, supported by original and creative use of language to convey a powerful idea about humanity and ideas.

The stories are not teleological or ‘satisfying’ in the traditional sense. Like real life there is not always a sense of resolution or clarity about what has happened. The climax and resolution are often about a moment of realisation and a subtle transformation that is sensed but not necessarily articulated. The reader is left to apply his or her own interpretation to the story or understanding of the characters.

Student activity

Imagine you are compiling a collection of a writer’s work.

- What would be the advantage of chronological order, starting at the earliest work?

- What would be the advantage of starting from the most recent work?

Approaches to this text:

Because this is such a large collection of stories some consideration has to be given to the goal of the course of study and the approach to be taken. Possible approaches:

- A study into the author as a short story writer looking for ideas, structure and language that connect the stories and show the development of the author’s style.

- A study into the author’s complete oeuvre across a few forms (essays, short stories, novel, poetry) where this resource provides some way in through the short story form.

- A close study of the short story form using Malouf’s stories as the springboard for students’ own writing.

- A study of an Australian author focusing on the short story form to explore cultural assumptions and discourses.

The activities that follow include support for all of these directions.

Ways of organising the learning

Given that there are so many stories, each student (or a pair of students) can be given a story to focus on – the different lengths of the stories needs to be considered in the allocation, which means those with shorter stories would take on more than one story. Teachers may want to consider which stories they want to exclude from the list of readings, to be then set aside for whole class close reading. It may be best to allocate the stories later in the unit, after the main ideas have been established.

The students complete this table, which should be collated as a Google doc so everyone can write into it. The final product can then be shared by the whole class to see if they perceive a pattern of ideas.

Students can then be given or can choose three stories with similar themes to work on for comparison.

| Story Title | Summary of plot (no more than two sentences) | Thematic concerns | Interesting quotes – no more than three | Characters and setting (What type of characters are they? What type of setting are they in?) |

Alternative 1: Teachers can use this story summaries table (PDF, 332KB) to help their selection of two to five stories on which to focus. This table can be developed further and built on as the students get to know the stories.

Alternative 2: Students focus on two stories from each book of stories and one from the last section from Child’s Play to gain an overview of the author’s work from different periods of his writing.

Alternative 3: The class can follow one of the themes as a class study or groups of students work on different themes.

Students can use the story map below after reading any of the stories.

The writer’s craft

Malouf on ‘The Book Show’, 1988: ‘The best way to write for me is to take myself away from everyday ordinary life. I don’t start with a plot – I start with a very general idea. The whole process of writing is in the very process of writing – objects turn up. Then I have to look at what I’ve done and say how are these things connected.’

Key elements of the text: plot, setting, character

In any good story all the elements of storytelling work together to support each other. Plot, setting and character support the ideas (themes) and emerge through the author’s style and the structure of the story.

Plots in short stories

For a full explanation of plot, access Plots in Short Stories (PDF, 235KB).

Setting/places

Refer to this description of two very different settings (PDF, 375KB) portrayed by Malouf – one natural, one domestic.

Settings are also an important part of identity. The relationship of the characters to their setting is an essential element in the stories. Look at how intense Angus’s relationship to his setting is in this passage (one sentence) from ‘The Valley of Lagoons’:

Extract from page 37: ‘I walked. And as I moved deeper into the solitude of the land, its expansive stillness – which was not stillness in fact but an interweaving of close but distant voices so dense that they became one, and then mere background, then scarcely there at all – I began to forget my own disruptive presence, receding as naturally into what hummed and shimmered all round me as into a dimension of my own being that it had taken my coming out here, alone, in the slumbrous hour after midday to uncover.’

Angus in ‘The Valley of Lagoons’ loves his surroundings but feels a sense of alienation, realising that he ‘too would leave’ (p. 44). This sense of alienation can be seen in other characters such as Sylvia in ‘A Change of Scene’ who sees herself as:

Extract from page 420: ‘a woman who has come sightseeing because she belongs nowhere . . . It is true I have no real place (and she surprised herself by acknowledging it), but I know what it is to have lost one. That place is gone and all its people are ghosts.’

In ‘Dream Stuff’ writer, Colin, also remembers the past when he goes back to his hometown Brisbane but becomes accidentally caught in a crime of passion and feels that he has lost touch with the place he knew: ‘The city he knew, and in one part of himself still moved in, was out there somewhere, but out of sight, underground.’

What we see in the three settings above is that place is often as much about dislocation as location, but that dislocation is very different in each story. Angus has walked into a timeless land. He feels the strongly spiritual beauty of the place but he is an intruder, a theme that Malouf returns to, acknowledging that the land holds a physical memory of an indigenous presence.

In ‘A Change of Scene’ the New and Old Worlds, as Malouf calls the places, create the disconnection. Memory of her family’s past links Sylvia to Europe but paradoxically also reminds her of a world that has been lost.

The third extract also plays on memory but in the urban Australian setting of Brisbane which becomes menacing.

Student activities

1. Responding

Read the three stories that appear in the stories above (‘The Valley of the Lagoons’, ‘A Change of Scene’ and ‘Dream Stuff’):

- What is the relationship of character to setting?

- How are ideas conveyed through setting?

- What similarities can you find in the settings?

2. Exploring other stories

- Which other stories have setting in their titles?

- Categorise these settings as: urban, rural, natural, marine, foreign, domestic, interior and consider what your expectations are of each setting.

- Annotate a passage using the above as examples.

- What does each setting convey about characters and ideas in each story?

3. Writing

Write your own setting, using an image you have found. Use verbs as much as nouns and adjectives to create powerful settings. You might copy the style of ‘The Valley of the Lagoons’ sample above, in starting with a simple and short sentence followed by an extended sentence in which images, feelings and character interact.

(ACELR017)

Characterisation

Unlike a novel, the short story should not have many characters, but like the novel our sense of the character emerges from the descriptions, thoughts, dialogue, actions and interactions offered to us. Our view of the character is also influenced by the point of view being offered. Who is observing and relaying the information to us? Can we trust the omniscient narrator any more than the character as narrator? Some characters may only be present to represent a particular attitude but even in the limited space of the short story, it is possible to build a strong character and to see some development.

A story where character is central is ‘Southern Skies’ told from the point of view of a boy whose parents are immigrants.

Extract from page 327: ‘From the beginning he was a stumbling-block, the Professor. I had always thought of him as an old man, as one thinks of one’s parents as old, but he can’t in those days have been more than fifty. Squat, powerful, with a good deal of black hair on his wrists, he was what was called “a ladies’ man” – though that must have been far in the past and in another country. What he practised now was formal courtliness, a clicking of heels and kissing of plump fingers that was the extreme form of a set of manners that our parents clung to because it belonged, along with much else, to the Old Country, and which we young people, for the same reason, found it imperative to reject. The Professor had a ‘position’ – he taught mathematics to apprentices on day-release. He was proof that a breakthrough into the New World was not only possible, it was a fact . . . We were invited to see in him both the embodiment of a noble past and a glimpse of what, with hard work and a little luck or grace, we might claim from the future.’

Interpreting the character: sample response

In this extract from the beginning of the short story ‘Southern Skies’, we see an opening statement that challenges the reader (why was he a ‘stumbling block’?), moves on to his age and suggests the importance of perspective before beginning a description of the character. The description focuses on one physical detail (‘hair on his wrists’) that leads to manners (‘formal courtliness’) and the way the character was perceived by others (‘ladies’ man’) representing the ‘Old Country’. It is here that we start to realise that the ‘stumbling block’ of the first sentence may have been the ‘Old Country’ that the young people found ‘imperative to reject’. Paradoxically, while the Professor represents the past, he is also a glimpse into the future because he has achieved a ‘position’.

What we realise from looking closely at this passage is just how many ideas can be conveyed through character descriptions. We start to realise that every character is caught in a system of relationships, so we know not just the Professor but the narrator and his family. In fact, it could be argued, that we learn more about the narrator. As an adolescent he focuses on the physical features, he identifies the older man with his parents, he seems annoyed by his parents’ insistence on a work ethic. We therefore also start to understand cultural difference and expectations of migrants through the eyes of the adolescent boy.

Student activities

1. Responding

- What are the ideas conveyed through this character description?

- How are ideas conveyed through character?

- Rewrite the character analysis describing what we find out about the narrator from the description.

2. Exploring other stories

- Which stories have character in their title?

- Look for descriptions of characters in other stories and copy one that stands out for you.

- Interpret the character using the above as a sample.

3. Writing

- Create a character for a story called: ‘Anything goes.’

(ACELR007)

Themes

In his chapter on Malouf’s short stories Don Randall focuses on two significant recurring themes: ‘Coming of Age’ and ‘Violence’. Randall traces the different kinds of violence in the stories and how these challenge the individual and the group but beyond this there is also the idea of being violated.

Violence/violation

Randall, in his critical work, identifies two main types of violence in the stories: random violence set against systemic violence. He writes: ‘While being detained by the police, Colin sees ‘drunks, derelicts, young toughs’ and ‘young Aboriginals’, all of whom the narrative voice characterizes as ‘the agents or victims or both, of a violence that was random but everywhere was on the loose’. The suggestion that violence, though ‘random’, arises among society’s marginal elements and then spills out, as it were beyond their ranks, must disturb some of the story’s interpreters.’ (p. 174)

He compares this with the more political acts of violence in stories that such as ‘Blacksoil Country’ and ‘The Last Speaker of His Tongue’ which condemn Australia’s violence against Aboriginals. Randall writes that ‘Blacksoil Country’: ‘presents violence as systemic rather than random, as the predictable expression of an unjust and divided society.’ (p. 175)

Against this we see the sensitivity of the adult couple to their son’s viewing of violence in ‘A Change of Scene’. They ‘worry insistently about what their child Jason has seen and understood of European violence, never really recognizing that their own experience of this violence is itself a harrowing initiation, a rending of the unconsciously fostered membrane of their Australian innocence . . .’ (p. 167)

Randall’s discussion on violence can be extended into other stories. Even from the earliest stories in the collection, violence is linked to the act of violation and the relationship drawn between the perpetrator and the victim. In both ‘The Prowler’ and ‘Eustace’ there is a sense of heightened excitement at the presence or thought of the violator. The media representation of the prowler captures the public imagination till the prowler ‘has become a victim of the newspaper’s hunger for events, but only for those events it has already created in its own dream-factory’ (p. 504). The involvement has become so intense for Senior Detective Pierce that, ‘What frightens him most is that he has begun to predict the crimes: the time the place, the kind of woman,’ and he becomes a suspect. The roles of violator and law enforcer become blurred and left for us to consider. The same exchange of guilt happens in ‘Eustace’ where girls in a dormitory welcome the intruder, fascinated by him and breaking the school rules and implicitly society’s rules about contact with strangers. The victims become complicit in this act of intrusion.

In a story such as ‘Out of the Stream’ the senselessness of violence turns on the self when Luke runs his finger along the edge of the dagger hanging on a hook at his grandfather’s place. He doesn’t understand the impulse, just that ‘you fell into such states, anyway, he did’. Innocence becomes lost in the violence that is part of the human state of being.

Student activity

Read the following stories and consider what Malouf is conveying about violence in society. ‘The Prowler’, ‘Eustace’, ‘Dream Stuff’, ‘Lone Pine’, ‘Blacksoil Country’, ‘The Last Speaker of His Tongue’, ‘Night Training’.

- Consider how the setting (urban, European, rural, domestic) affects the portrayal of violence.

- Categorise the acts of violence as systemic or random.

- Read the stories chronologically (from last story in book forwards) to see if Malouf is changing the way he depicts violence and what he says about violence.

Coming of age/thresholds

While Randall sees ‘coming of age’ as the significant theme across the stories, he also sees that in the collection ‘Dream Stuff’ this ‘coming of age’ is not effortless or complete: ‘the focal characters characteristically do not come of age, do not move cleanly, unambiguously into more clearly mapped, more stable and secure modes of being. They carry across the threshold at least a portion of their former confusions and ambivalences.’ (p. 164)

This uneasy transition is central to Malouf’s work where characters ‘do not manage to sort out and simplify the complexity of experience. In Malouf’s view this is not what maturation is, not how one matures. Life includes its moments of graduation, but one graduates, most typically, into new realms of difficulty and perplexity.’ (p. 166-167)

In his brief discussion on ‘Out of the Stream’ Randall shows how even the punctuation serves to show the coming of age. Extract from page 396: ‘You could let each thing happen, one thing after the next, in an order that once established would carry you right though and over into – He stood very still letting it begin.’

Randall writes: ‘The sentence’s final dash is eloquent: the boy seeks a crossover into some new mode of life his adolescent confusion does not allow him to conceive clearly.’ (p. 166)

In Malouf’s stories, coming of age is linked to a loss of innocence expressed most eloquently in the story ‘War Baby’. ‘We lose whatever innocence we might have laid claim to the moment we are drawn into that tangle of action and interaction, of gesture and consequence, where the least motion on our part, even the drawing of a breath, may so change things that another, close by or far off, will be nudged just far enough out of the line of the clear line of his life as to be permanently impaired. That, so Charlie would have written . . . was the price of living.’

Student activity: responding

1. Read the story ‘Out of the Stream’ and focus on the following quotations to discuss the way Malouf structures his story to show the developing transition. Include a discussion of the use of images of light and dark.

- ‘The boy stood at the doorway and was not yet visible.’ (p. 388)

- ‘He would step out soon – but as what?’ (p. 388)

- ‘He stepped out of the lee of the white giant, in T-shirt and jeans, his hair combed wet from the shower. The two-edged sword went swinging.’ (p. 388)

- ‘At the moment of his first stepping in across the threshold out of the acute sunlight, he had entered a state – he couldn’t have said what it was, but he felt the strangeness of it.’ (p. 396)

- ‘He felt oddly happy – for no reason, there was no reason . . . He was back in the stream again – one of the streams.’ (p. 399)

- ‘So he set the two places at the kitchen table, then stood for a moment and looked out into the dark. It seemed larger, more comprehensible, because it lay over the sea and you saw it as an ocean whose name you knew and knew the other shore of, glittering full under the early stars; though the dark was bigger than any ocean, bigger even than the sky with its scattered lights.’ (p. 399)

2. Read other stories about coming of age: ‘The Valley of Lagoons’, ‘At Schindler’s’, ‘Southern Skies’, ‘Sorrows and Secrets’, ‘Out of the Stream’, ‘The Sun in Winter’, ‘Bad Blood’, ‘A Medium’.

- Is there a defining moment that causes the ‘coming of age’?

- How does the relationship to the adult world affect the ‘coming of age’?

- After reading the stories do you agree with Randall’s statements that appear above on coming of age?

Memory

There’s a close association for me but it’s a mysterious one between the process of memory and the process of reflection and the actual music of the writing.

Malouf, ‘Memory, reflection and the music of writing’ in the Macquarie PEN Anthology of Australian Literature interview.

Student activity

Watch the video of David Malouf speaking about the importance of memory in his writing:

‘Memory, reflection and the music of writing’ for the Macquarie PEN Anthology of Australian Literature.

Read a story or stories and discuss the way memory unfolds in them. You should also consider the way time acts with memory.

Possible stories: ‘The Valley of Lagoons’, ‘Mrs. Porter and the Rock’, ‘At Schindler’s’, ‘Dream Stuff’, ‘Jacko’s Reach’, ‘Southern Skies’, ‘The Only Speaker of His Tongue’, ‘A Change of Scene’, ‘In Trust’, ‘A Traveller’s Tale’, ‘A Medium’.

Extended writing

Write an essay comparing how a theme is developed across two or more of the stories. How effectively have the values and attitudes been conveyed through the two stories?

(ACELR011) (ACELR005)

Style

Throughout Malouf’s work language operates as a sensuous tool through which we come to understand the meaning and texture of our world.

Bernadette Brennan, ‘Singing it anew: David Malouf’s Ransom’, ASAL Special issue: Archive Madness

Just like a painter or a musician or any other creative actor, every author has his own style. This can refer to the choices of words, the sentence structure, the imagery, the story structure, the development of the point of view.

Student activity: Long sentences

One feature of Malouf’s writing is the long sentence, adding a rhythm and the cascading effect of images piling up. Consider the sentence that appears below and annotate it with arrows going to explanation boxes which say the following:

- Cliché: which suggests the barrier created by silence

- Paradox: created of silence being noise

- Pronouns: show person feels separated from others

- Colon: introduces the list of metaphors that capture the sense of silence

- Personification: of metal juxtaposed with human screams and connects the noise to the war

- Onomatopoeia: experience of war emerges through the listing of sounds

- Modal: ‘might be’ reinforces the fear that arises from uncertainty

- Antithesis: the natural and unnatural are set against each other

- Contrast: sentence begins with silence and ends with loud music.

Extract from ‘War Baby’, page 93: ‘The wall of silence he felt between himself and others, which he refused to breach, was noise of a kind they could not even begin to conceive: so dense with the scream of metal and the lower but distinguishable screams of men, with the splash of heavy objects through oil-licked swamp, and night calls out there in the stilled other world of nature that might be birds but might also be the location signals of a waiting enemy, and with heartbeats and the thump-thump of rotor blades, that not even the music he liked to listen to, and which his aunt thought unnecessarily loud, could block it out.’

In terms of structure this sentence begins with a clear statement that is immediately contrasted and followed by elaborations. The list of sounds propels the sentence to its ending, capturing the despair of Charlie Dowd as he tries to escape war memories. The inability of others to understand is reinforced by his final comment about his aunt thinking the music ‘unnecessarily loud’.

Listing and word choice

Now consider a sequence from another story (‘In Trust’) (PDF, 129KB). Like the one above it depends on listing to create the effect of an overwhelming number of objects. This time you should take part in the writing and add your own objects, images, words where spaces have been provided and appear in bracketed numbers. For (5) you should provide a phrase not just a word.

- Is the order of words in each list random or do you think it has a sense of order?

- If you changed the order of some of the words in the list would this change the effect?

Dialogue and punctuation

While the stories are mostly interior narratives, Malouf also uses dialogue to show the interactions that pass between people. The following dialogue is from ‘Southern Skies’ that is narrated from the point of view of an adolescent man.

Student activity

- Add the punctuation to the second paragraph below – this includes a pair of dashes and one exclamation mark. Think carefully about the effect you want. The punctuation adds rhythm and changes the pace. You should then read your version aloud to a partner and compare where each of you placed the punctuation. Return to the text to see where Malouf has punctuated. What effect has the different punctuation created?

- Find the sentence fragments and the complete sentences. Why do you think writers use sentence fragments?

- Find the metaphors and similes and explain their effect.

- What is the effect of the lexical chain in the words ‘large huge bigger’?

- What is the effect of repeating the personal pronoun ‘you’?

Extract from ‘Southern Skies’, page 337: ‘What do you do up there on the roof?’ I asked, my mouth full of bread and beer, feeling uneasy again now that we were sitting with nothing to fix on. I make observations, you know the sky, which looks so still, is always in motion, full of drama is you understand how to read it like looking into a pond hundreds of events happening right under your eyes, except that most of what we see is already finished by the time we see it ages ago but important just the same such large events huge bigger even than you can imagine and beautiful since they unfold you know to a kind of music to numbers of infinite dimensions like the ones you deal with in equations at school but more complex and entirely visible.’

Sentence order

The sentences that appear below are in no order. Organise them into an order that works and then check this against the text. Explain how the sentences follow each other with the idea of one sentence building into the sentence that follows.

- A change.

- The magic I’d felt when they just stood and looked, as if I was some creature like a unicorn maybe, had come from them.

- He had put us outside the rules, which all along, though he didn’t see it that way, had been their rules.

- Now it was lifted.

- That change in him had changed me as well and all of us.

- He had removed us from protection.

- I didn’t know it neither, but I felt it.

(‘Blacksoil Country’, p. 278)

Student activity: Conclusions about style

. . . Contemplative and inward: most of my writing has been that

Malouf, ‘Memory, reflection and the music of writing’ in the Macquarie PEN Anthology of Australian Literature interview.

The above activities show the use of long sentences, sentence fragments, dialogue, images, contrasts, metaphorical language, punctuation, listing and word choice in Malouf’s work. You can also see some of the repeated motifs that are part of Malouf’s work: the silence, rules, the skies, the objects.

- Locate motifs and techniques in other stories in the collection.

- Find interesting passages and see what other stylistic features you find.

- Write a paragraph with examples on what you think are the characteristics of Malouf’s style

(ACELR005)

Close studies

For additional close studies and activities refer to these sections:

- Close Study One: ‘The Sun in the Winter’ (PDF, 254KB)

- Close Study Two: ‘The Only Speaker of His Tongue’ (PDF, 207KB)

Synthesising tasks

1. Responding

Use the text annotation strategy (PDF, 188KB) to explore a story.

2. Writing

In this task students look at the beginning and ending of a story they have not studied and construct a possible story in between that reconciles the beginning and ending.

Discuss and predict

- What does the introduction suggest might follow?

- What idea does the ending suggest might be the central focus?

- What kind of person might the main character be?

- Are there any clues to place and time?

- What setting will you use?

- Now work in groups to map a story.

| Title | Beginning | What happens in the middle? | Ending |

| The day Greg Newsome turned seventeen he joined the University Air Squadron. It was 1951. | But the one who was there in the dream was not there to hear it. He found himself staring into the darkness, fully awake. | ||

| Driving at speed along the narrow dirt highway, Harry Picton could have given no good reason for stopping where he did. There was a pine. | He made quickly now for the car and the group his family made, dark and close, beside the taller darkness of the pine. | ||

| The rock is Ayres Rock Uluru. Mrs Porter’s son, Donald, has brought her out to look at it. | She also knew for certainty, that she would live forever. |

Peer response

- Read all the group stories to each other and then select which one you like best and why.

- Then read the whole Malouf story and discuss whether this was expected or unexpected.

(ACELR018)

Rich assessment task one: Creating artwork from story

Visual artists respond to literature

As part of the celebrations for David Malouf’s 80th birthday the Museum of Brisbane asked artists to create an artwork that reflected one of his novels. They talk about the process in the video (artists speak from 2.23).

- Your task is to select a story and then describe the artwork you might create that captures the essence of that story – or you can select from existing art that connects with the chosen story. Use the discussions on the video as a guide to explain the motivation for the art choice. The artwork can be a collage of different art works.

- The artwork will be presented as part of a spoken presentation explaining the decisions that were made.

(ACELR017) (ACELR014)

Rich assessment task two: Maloufean style

Students should read at least five of Malouf’s stories, collect notes using the activities in this section and then respond to this essay topic:

- Whichever story we read we find that there is a distinctive Maloufean style and attitude that absorbs the reader’s mind and ear.

Write an essay about the ‘Maloufean style’ focusing on one of the stories but referring to others, showing how Malouf uses his skill as a writer to convey important values and attitudes.

(ACELR006) (ACELR009)

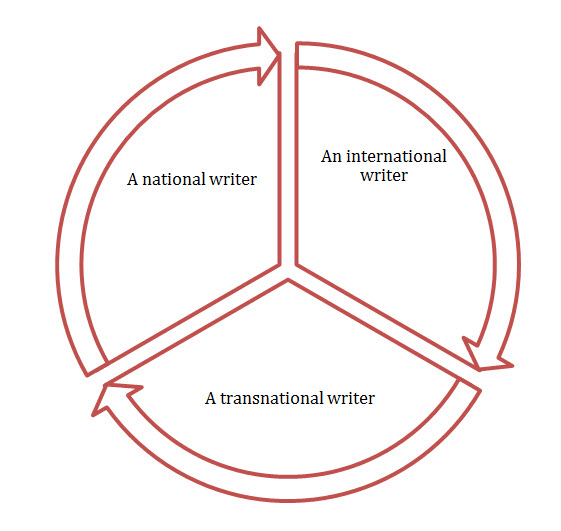

Malouf as a ‘transnational’ writer

‘Australian writers and Australian literature have never been confined to the boundaries of the nation . . . From the beginning Australian writers have travelled and lived abroad, often becoming ex-patriates, and they have always been influenced by the literatures of other cultures. Australian writers and readers then, have always belonged to what French critic Pascale Casanova calls ‘world literature’ . . . she seeks to restore the transnational dimension to the study of separate national literatures.’

Robert Dixon, Professor of Australian Literature, ‘Australian Literature and the Republic of Letters’, mETAphor, Issue 1, 2013

In order to understand Malouf’s influence and significance as a national and international writer we need to engage with definitions of national literature. The term ‘transnational literature’ coined by French critic Pascale Casanova and cited by Professor Robert Dixon in his consideration of Australian literature is immediately applicable to David Malouf who has travelled and been an expatriate (living and writing in Italy) and whose work is markedly influenced by literatures of other countries, especially European writing.

Malouf’s writing is often about the strained and difficult relationship between Europe and Australia. He writes about Australians who have come from Europe, or whose parents have come from Europe, and Australians who go to Europe. For many of his characters, Europe is intricately connected with memories which create links to the past but he is also ever-conscious of the indigenous voices in the Australian landscape. The fraught relationship between indigenous people and colonisers creates the stimulus for many stories and is the undercurrent in other stories.

‘Australia is not one place’, he writes in the 1984 Blakelock lecture (in My First Place2014). This consciousness of the many voices of Australians and his negotiation between the international and the national that form the plots for his stories, as well as the awards he has received both nationally and internationally, mark him as a truly transnational writer.

Because of his engagement with indigenous issues Malouf is also often described as a post-colonial writer. Indigenous people with their memories connecting them to land feature in Malouf’s stories.

What is Malouf saying about Australia?

Australian Places

Australian places dominate Malouf’s short stories and offer inspiration whether they are urban or rural.

The Complete Stories begins with a very ‘Australian’ story, ‘The Valley of Lagoons’ set in rural Australia, with a rugged landscape surrounding a country town from which young people will escape, and where hunting is a masculine distraction. The rural landscape is immediately romanticised in the first sentence evoking an earlier time through memory: ‘When I was in the third grade at primary school it was the magic of the name itself that drew me.’

The Valley of Lagoons is part of Malouf’s own life story and appears in the essay ‘The north: the exotic at home’ where he shares the experience of first encountering the Valley of the Lagoons at the age of 21 on a five-day hunting trip, saying: ‘it presented a different Australia from the one that is sometimes offered as the real, the harsh, the authentic one. It was not a desert but a vast water park crowded with creatures.’

The novella that emerged was Fly Away Peter but the place re-emerges in the short story, ‘The Valley of Lagoons’. While Malouf acknowledges that this quintessentially Australian setting is also a site of indigenous memory (‘[Matt Riley] had re-entered a part of himself that was continuous with the place, and with a history that the rest of us had forgotten or never known.’ p. 31), he also admits the attraction of the land to the colonisers through Angus. He realises, ‘This was the country I would go on dreaming in.’ (p. 45). The same longing to connect to the land is central to the story ‘Blacksoil Country’ where the narrator, who tells his story from the grave, demonstrates the strong desire to be part of the land ‘blending my white grains with its many black ones.’ (p. 280). The land becomes an inclusive force that unites the two peoples.

Like all writers there are some places, ideas, feelings that Malouf keeps returning to.

Australian events

Malouf’s stories often make important political statements. In his essay ‘The One Day’, Malouf acknowledges the importance of national days in bringing us together ‘whatever our individual differences and divisions, as a single community, a single people involved in a common enterprise’ but he rejects Australia Day which he says has ‘no general claim on our affection and is seen by many of us as an occasion that is not fully inclusive – as it never can be while for indigenous Australians it is seen, and more importantly felt, as a day of conquest and dispossession.’ This attitude can be seen as the stimulus for his story ‘Great Day’ with a middle class educated family turning their back on the celebration deciding to be ‘non-participants in the national celebrations’ (p. 297).

War is another event that Malouf keeps returning to in the stories but the focus is on the impact on the individuals. In this way all the wars merge and become a war against the individual. For soldier Charlie Dowd in ‘War Baby’, the Vietnam War is as much about his father who died at war as his own experiences, while ‘Night Training’ reveals the harassment many soldiers face from their own leaders.

Research and discuss

- Who do you think Malouf would include in the definition of Australian?

- How is Malouf representing Australians and their interactions?

- What is he saying about what Australians value?

- To what extent do you believe this is true?

- What is Malouf saying about Australians and the world?

Activities

Note: Many of the following activities will refer students to the book of collected essays by Malouf, First Place (2014). See bibliography.

1. Researching the international scene

Given the importance of Malouf as a writer both nationally and globally, it is important for students to conduct research into the awards he has received and to know why these are so important. He has twice received the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for South East Asia and the South Pacific Region. He has been acknowledged with prizes in Dublin and France as well as Oklahoma (Neustadt International Prize for Literature). The ACU symposium introduction is a good place to start to research Malouf’s international profile as it lists his awards, his work and the prizes he has received.

2. Understanding the interplay between texts

Students should read the texts: the novella Fly Away Peter, the stories ‘The Valley of Lagoons’, ‘War Baby’ and the essays ‘The North: the Exotic at home’ and ‘The One Day.’ They can construct a premise that explains the interaction of ideas, characters and places among the texts and write an essay that argues the case.

3. Representations of indigenous people in Malouf’s writing

Students can research the representations of indigenous people in Malouf’s writing and why Malouf might be regarded as a post-colonial writer.

Relevant stories: ‘Blacksoil Country’, ‘The Valley of Lagoons’, ‘The Last Speaker of His Tongue’, ‘Mrs. Porter and the Rock’

Relevant novel: Remembering Babylon

Relevant essay: ‘A spirit of Play: The making of the Australian Consciousness’ by David Malouf (First Place)

4. Representations of Europe in Malouf’s writing

Students should consider: How does Malouf view Europe in his stories?

Relevant stories: ‘A trip to the Grundelsee’, ‘The Sun in Winter’, ‘A Change of Scene’

Rich assessment task three

Australian, international or transnational writer?

This question can be explored by students after reading the essay ‘A spirit of Play: The making of the Australian Consciousness’ by David Malouf (First Place)

- As a class, students add definitions to the table below.

- Students then divide into three groups. Each group will focus on only one part of the argument: is Malouf a national, international or transnational writer?

- Students in each grouping need to develop points to support their argument, using the stories and any additional reading about Malouf.

- This work is to be shared with the whole class who can then argue the case in an open class discussion.

Poet or prose writer?

One of the questions that frequently comes up when Malouf is being interviewed or discussed is the way he moves fluidly between the different forms that he writes in. Is he pre-eminently a prose or poetry writer? This was part of a discussion between Ivor Indyk (publisher and academic), Jaya Savige (poet), and Yvonne Smith (academic) in the year of Malouf’s 80th birthday on the Radio National program: ‘A publisher, an academic and a poet on Malouf’, Books and Arts, Radio National, 20 March 2014. (Transcript by Mel Dixon, resource author.)

(Start at 14 minutes.)

Jaya Savige:

‘A lot of his poetry is brimming with virtuosic music . . .’

‘as a prose stylist that feeds back into the poetry to some extent. Where most poets will probably end a line, David will have two extra clauses which will run over extra lines, and his skill at following a thought through beyond where a poet would normally cease that thought is something that I notice anyway.

[Interviewer: You mean in his prose] . . .’

‘No, perhaps controversially, I’m suggesting the opposite that his skill as a prose writer with the sentence and the syntax, juggling the many clauses with say of a multi-barrelled sentence, that is sustained in a remarkable way in the poems.’

Ivor Indyk:

‘I find it impossible to say which way it goes for me . . . from the poetry to the prose; that he is fundamentally a poet and that his prose both in his perspective, his use of imagery the way he constructs his novels essentially like poems really, but more than anything else in terms of his rhythm, he is fundamentally a poet . . . There is a distinctive Maloufean rhythm. It’s lyrical, obviously it’s accumulative; David insists in both his poetry and his prose that all things are equal that the most ordinary things contain as much significance as the largest things so there are no hierarchies in his work. Therefore the rhythm is one of accumulation, of curiosity and also of attentiveness. Jaya refers to this capacity for wonder in his [Malouf’s] writing. He’s always attentive and curious and it’s interesting, I think, that this attentiveness which we associate with a lyrical poetic sort of stance, is also that of the essayist, because the curiosity leads him to expand ideas, to look behind things to see their causes and in front of them for their consequences. So I can’t really distinguish very clearly the priorities in David’s capacity as an essayist, a poet, a novelist or indeed a librettist for that matter.’

Yvonne Smith on Malouf – poet or prose writer:

‘. . . [the] way that ideas and images flow between his poetry and his prose is one of the delightful things . . . in the novels and sometimes you can find him working over an image in a poem that is taken over and expanded in a work of prose’

‘. . . it feeds back and forth’

‘. . . it’s lovely to see that interconnection.’

Malouf on Malouf – poet or prose writer:

‘I think the quality of reflectiveness in the writing and the determination of the writing to be inward but to come from some very inward non-logical, non-rational place is the thing that distinguishes it rather than whether it is written strictly as verse or strictly as prose – although both verse and prose are different; they’re different in the density with which the language works, but for me they’re not necessarily very different in the attention I would give to rhythm or the musical quality of the writing.’

Students can consider the arguments offered here and test these against their own reading. An excellent source of Malouf’s poems is available at the Australian Poetry Library.

Sharing lines

The purpose of this task is to appreciate the poetic features of the short stories and use these to create original poems.

Students can each be assigned one of the short stories. They have to find a musical poetic phrase or sentence and copy this down on a piece of paper. This can also be copied on to a google doc site or a wiki for sharing. (Physically sharing the poetic lines and silent reading are sometimes more effective than the Google Doc site so it is recommended that both methods below are used.)

- Holding their pieces of paper, students form two lines.

- They hand their paper to the person paired with them in the lines.

- They read each other’s lines in silence and think about them.

- Then the first person of one line goes to the end of the line so that a new pair faces each other.

- The process continues until the line returns to the original pairings.

- The lines from the stories are then pinned onto a display board.

- In the next phase of this activity students select a few of the lines that they liked.

- They can return to the board to copy these down and browse the selection or they can reorganise these in the form of a poem.

- They may need to add some words or lines or even remove some words.

- They then read their poems in small groups and choose one from the group to share with the whole class.

(ACELR003)

Rich assessment task four: Acts of translation

Part 1 – from poetry to prose and from prose to poetry

Students should experiment with style. They can create a poem out of one of the stories and then create a short story out of one of Malouf’s poems, selecting a line or word or just using the ideas to create their own new composition. An excellent source of Malouf’s poems is available at the Australian Poetry Library.

This should be followed by a reflection on the process of writing and how they adapted the elements of one form to the other. What were the difficulties encountered? What did they note about Malouf’s writing style as they adapted the original work? What strategies did they apply to the reworking?

Now return to Malouf’s short stories. Students think carefully about the task of adaptation.

- What words need to stay?

- What images do we need to capture?

- How might film or video show the ideas?

Part 2 – translating a short story into film

Students have been asked as readers of Malouf to offer informed advice on the possibility of filming Malouf’s stories and which one they would recommend, if any. They need to justify their response with knowledge of film techniques, the stories themselves and about adaptations.

‘The words are superfluous in the film context.’

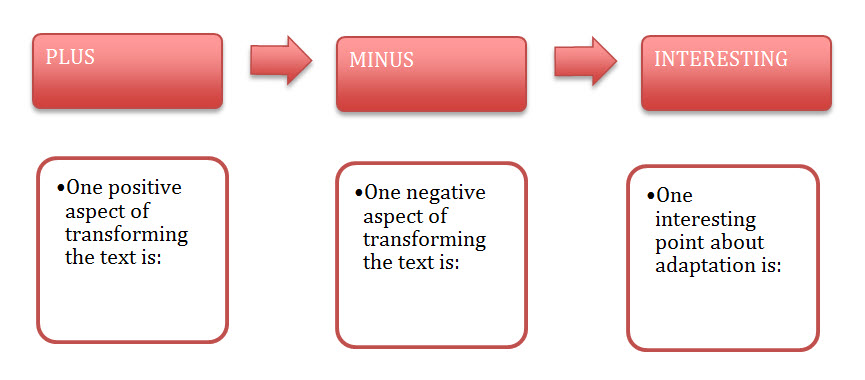

Students watch and listen to the Britannica video on short story to film to gain some understanding to the process of adaptation. They should then:

- copy one positive aspect about the transformation of story to film under the heading PLUS

- write one negative aspect of transforming short story to film under the heading MINUS

- find an interesting point about adaptation.

Are the stories transferable to film? Complete this table and write a paragraph explaining your decision.

| Good features of the story for transferring to film. | Problems with transferring the story to film. | Possibilities for the filming – music, camera, editing decisions that could be made. |

Students can then work on their set task.

Part 3 – reflection and summing up

- Write one thing you learned about David Malouf and his writing.

- Describe an element of his writing style that stood out for you.

- Write down which story you liked the best.

- What did you learn about the craft of writing short stories?

- What did you come to understand about Australian writers?

- What do you think makes David Malouf such an important writer?

(ACELR014) (ACELR017) (ACELR016)

(6 votes, average: 4.50 out of 5)

(6 votes, average: 4.50 out of 5)