Essay by Bernadette Brennan

Has our public language really deteriorated to the point where we no longer understand what is being said? If so, when and how did this happen, and how worried should we be? In a world of spin and management speak, is there really any way the average citizen can restore the meaningfulness of public discourse?

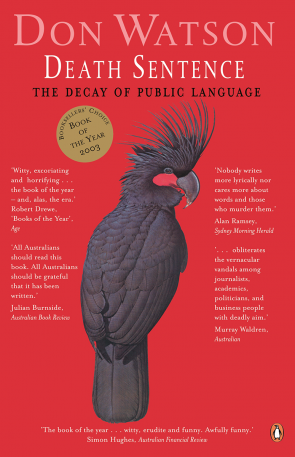

Author and speechwriter Don Watson believes that we can rescue, indeed resurrect, the rich and nuanced texture of language and, in Death Sentence: The Decay of Public Language(2003), he not only demonstrates how dire things have become but also makes suggestions on how strategic intervention may stymie what he perceives to be the atrophy of language.

The historical context

Death Sentence is part of a historical, ongoing conversation about the power of language to shape our imagination and, therefore, our world. As far back as 1523, when the first English lexicon was printed in London, debates circled around how best to strengthen the English tongue. Throughout the sixteenth century, European words were imported into the English language as a way of expanding the vocabulary and imbuing English culture with a sense of cosmopolitanism. By the time Samuel Johnson published his Dictionary of the English Language (1775) – drawing on Richard Rowlands’ 1605 work A Restitution of Decayed Intelligence – his intention was to use the dictionary to preserve and revitalise what he saw as the pure, monolingual English language. Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, ‘English royalty and nobility’ viewed language capacity as ‘a measure of national power’ (Lancashire p. 24). That relationship between language and the State has never changed.

Jumping ahead to 1946 we discover, in George Orwell’s essay ‘Politics and the English Language’, an urgent plea to rescue what he sees as a ‘decadent’, collapsing civilisation and language. The two, he insists, are inextricably linked. Watson’s Death Sentence can be read as an extended response to these historical concerns about the relationship between language and power, language and polity. Like Orwell, Watson insists it is time to act. ‘Vigilance is needed’, he cautions, ‘an argument concerning the public language is an argument concerning liberty’ (Watson p. 3).

Framing the argument

Watson’s basic premise is that the decay of language leads directly to a diminishment of the democratic process. Because language structures thought, the rise of managerial language and media spin threatens to undermine an individual’s capacity to think deeply, to feel fully or to reason independently. Mechanised language, writes Watson, ‘removes the need for thinking: this essential and uniquely human faculty is suspended along with all memory of what feeling, need or notion inspired the thing in the first place’ (p. 8). Orwell earlier had put it like this: the English language ‘becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts’ (Orwell ‘Politics and the English Language’).

Death Sentence is deliberately polemical. Part of Watson’s complaint is that he sees little or no resistance to the inundation of ‘shapeless, enervating sludge’ (p. 1) into public life. He wants to provoke a response. He wants his readers to become indignant, to resist the slide, to engage actively in his fight to re-animate language and to hold those in power accountable for what they say. He uses four strategies to achieve his aims. First, he writes deliberately confrontational, opinionated prose. He labels managerial language ‘clag’, ‘sludge’ and ‘gruel’. Comparing various national anthems, he notes: ‘“Advance Australia Fair” is simply thick'(p. 78). He likens the invasion of universities by management speak to Germany’s invasion of Poland. He writes: ‘An airhead is no less an airhead for having a command of grammar’ (p. 152). And so on.

Second, he punctuates the text with multiple epigraphs ranging from the sublime to the excruciatingly banal. Occasionally he engages directly with a passage in order to demonstrate how and why it is such effective writing. He lauds Lincoln’s ‘verb-filled’ Gettysburg Address (p. 84) and Martin Luther King’s rhetorical strategies; he delights in the power of the active tense; but for the most part Watson trusts his reader to appreciate what constitutes great writing. That is to say, he empowers his reader.

Watson’s third, and arguably most risky, strategy is to reiterate his complaints again and again. Death Sentence builds in crescendo to something of a rant – against George W. Bush, against John Howard, against teaching students deconstruction, against government memoranda, and against the marketing mindset now governing universities.

His fourth manoeuvre is to conclude Death Sentence with a glossary that not only suggests alternatives to clichés and empty metaphors, but also invites active participation in the construction of new sentences through various exercises.

The art and power of public speech

Watson values two types of public language: clear, precise, unadorned words that convey information; and a more rhetorical, though genuine, language that operates as a ‘vehicle of the imagination and the emotions’ (p. 23–4). In 1992 he accepted the position of speechwriter to the then Prime Minister Paul Keating. It was Watson who penned Keating’s now famous Redfern Park Speech, a speech in which Keating appealed to the primacy of imagination as a means to rectify injustices of the past. In a trusting, inclusive gesture, Keating addressed his audience thus:

It begins, I think, with that act of recognition.

Recognition that it was we who did the dispossessing.

We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life. We brought the diseases. The alcohol.

We committed the murders.

We took the children from their mothers.

We practised discrimination and exclusion.

It was our ignorance and our prejudice.

And our failure to imagine these things being done to us.

With some noble exceptions, we failed to make the most basic human response and enter into their hearts and minds. (Keating ‘Redfern Speech’)

The short sentences, the lack of adornment and the active tense, demonstrate the kind of writing Watson champions. Keating believed that speeches were ‘the most noble form of public life’ and that they deserved ‘to survive political spin, the ten-second grab, the simple, uncritical, anonymous questions at the doorstop – all the devices that absolve the politician from explaining, indeed thinking’ (Button p. 239). Watson wrote such speeches as a way of encouraging audiences to understand and become involved in shaping the narratives of their nation.

As an effective speechwriter, Watson appreciated the power of emotion to engage an audience. In Death Sentence he not only calls for a higher standard of public language, he also argues the need for a stronger moral and ethical engagement with language, especially its power to inspire greater imaginative vision.

Why is this decay impervious to satire?

Watson ponders when, and why, the serious decay of public language began in earnest. He pinpoints the 1980s as the time when economic focus drove a merger between political and business language. His fury at, and disdain for, this ferocious assault are evident through his choice of verb and his sardonic use of ‘religions’: ‘In the years since then business language has been steadily degenerating, mauled by the new religions of technology and management’ (p. 24).

Corrupted language always generates humour, the most innocent example being the malapropism. Predictably, Watson includes Donald Rumsfeld’s ‘known unknowns’ speech in the margin (p. 45). To date, that speech has recorded nearly 300,000 YouTube hits. This kind of humour works through a form of dramatic irony; the audience is wiser than the speaker, and the audience appreciates the vacuous nature of the language.

Death Sentence was published nine years after the first episodes of the extremely popular television series Frontline, and at a time when Frontline was a set text for HSC extension 1 English students. Why had the satire had such little effect? Since that time, audiences have been entertained, and perhaps educated and alarmed, by precisely the kind of spin Watson rails against on The Chaser’s War on Everything and, more recently, The Hamster Decides. Spliced segments of politicians repeating meaningless phrases over and over are amusing. Their continued prevalence attests to the truth of Watson’s thesis about the seemingly unstoppable degradation of public language. Obviously, marketing, the sound bite, the message rather than meaning, dictate political discourse.

Language and the limits of experience

Watson includes a crucial epigraph from German philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein: ‘The limits of my language mean the limits of my world’ (p. 95). Language can open us up to the world and open the world up to us, but degraded language entraps us, it stifles our imaginative openness. In his Quarterly Essay ‘Made in England’, published the same year as Death Sentence, David Malouf celebrates the rich texture of the English language – the language of Shakespeare – that he believes shapes English speakers around the world. Like Watson, Malouf affirms that language is so much more than a means of communication:

It is all very well to regard language as simply ‘a means of communication’. It may be that for poor handlers of a language and for those to whom it is new and unfamiliar, who use it only for the most basic exchanges. But for most of us it is also a machine for thinking, for feeling; and what can be felt and thought in one language – the sensibility it embodies, the range of phenomena it can take in, the activities of mind as well as the objects and sensations it can deal with – is different, both in quality and kind, from one language to the next.

… language is one of the makers of history, and the history it makes is determined – limited – by its having developed in one direction rather than another … it is also shaped and changed by what is said in it. (Malouf p. 44)

Malouf’s primary focus is literary language, not Watson’s public discourse, yet he arrives at a similar conclusion about the power of language to shape and possibly limit experience, thought and history.

Watson’s witty title relates directly to the book’s message. Language, he is saying, has a playful depth. His subtitle also carries an important warning: language is a living entity liable through neglect to waste or rot, active processes that are currently under way. Watson is not objecting as such to new forms of communication or to poor grammatical skills. He prefers a couple’s response to his dog – ‘Jeez, his fur is soft as’ – to the possible clichés: ‘Soft as silk, as down, as a baby’s bum’ (p. 152). Unlike Samuel Johnson all those centuries ago, he does not want to lock English into some list of pure words. He loves the way ‘cool’ has become part of his lexicon. He is excited by the idea that 20,000 words are added to the English language each year. The decay he is fighting against is the sameness, the unthinking sameness, of the ubiquitous clichés and managerial speak that increasingly dominate and structure our institutions and our lives.

Both Watson and Malouf return to the foundational history of Australia as a defining moment in determining our approach to the English language. Watson compares the laconic Australians unfavourably to the more loquacious Americans, wondering if ‘we needed a Mississippi or a Missouri or a Civil War or slavery to inspire us’ (p. 70). Australians, he says, are slovenly, ‘it was not in our breeding to be eloquent’ (p. 71). Interestingly, he wonders if it was because there was ‘too much inner chaos; caught as we were between wanting to be like both the civilised English and the self-assured Americans’ (p. 71). Malouf would not disagree, but he is more optimistic about our facility with language. He puts it more poetically when he muses about how Australians deal with their Britishness: ‘we cannot remove … the language we speak, and all that is inherent in it: a way of laying out experience, of seeing, that comes with the syntax, a body of half-forgotten customs and events, fables, insights, jokes, that makes up its idioms, a literature that belongs’ to English speakers around the globe (p. 65). Perhaps the real difference is that Malouf is steeped in an imaginative world whose language is always already the language of the body; Watson, on the other hand, is immersed in the real body politic. Where Malouf appreciates how language and imagination open up our world to immense possibility, Watson wrestles with a degraded public language that ‘lacks almost everything needed to put in words an opinion or an emotion; to explain the complex, paradoxical or uncertain; to tell a joke’ (p. 3).

Contemporary relevance

Death Sentence was first published over ten years ago. Is it still relevant? Arguably the answer is: more so than ever. Death Sentence opens with the assertion that public language has not yet seeped into private discourse. By 2014, director and playwright Michael Gow begs to differ. Gow’s new drama Once in Royal David’s City was performed at Sydney’s Belvoir Theatre from 12 February to 23 March 2014. Like Death Sentence, the play, inspired by Gow’s ‘disdain for the clichés of contemporary social interaction’, has been labelled a ‘call-to-arms’. According to Gow, the play is the story of a man ‘trying to say something meaningful in a sea of meaningless crap’ (Blake SMH).

In 2012, James Button, having worked briefly as speechwriter to Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, published his memoir Speechless: A Year in My Father’s Business. One of the motivating forces driving Button’s memoir is the need to re-engage a disaffected public in the political process by telling ‘fascinating and vital’ (Button p. ix) stories of politics and government. As the new boy in Canberra, Button turned to Watson for advice and was told that to be a good speechwriter he needed to ‘read a lot and widely’ (p. 32), to spend time in the library. From Watson he learnt that ‘a good speech without clichés is “telling people something about themselves they had not thought of before”'(p. 33). Things did not work out with Rudd, but before Button left Canberra he was asked to help colleagues with their writing skills. He initiated writing seminars and began a blog titled ‘The Dejargonator’, on which fellow public servants ‘were asked to post examples of grisly official prose’ – the kind that litter Death Sentence – and to offer clear alternatives (p. 164). Button, like Watson before him, found that no one liked ‘mangagement-speak’ and that most people were amused and perplexed by the proffered examples. No one admitted to writing in this way. Death Sentence was the most borrowed book from the parliamentary library, yet still the jargon continued to appear in departmental reports. Why?

Button’s answer is instructive. Jargon persists, he suggests, because it manages risk. Management speak that refuses to clarify exact initiatives or outcomes is actually a sign of powerlessness:

The writing plods because it has no confidence in its own truth. This is the paradox of bad public language. What looks to outsiders like an exercise of power, an intent to shut others out, in fact expresses a kind of powerlessness. Unsure what to say, writers find it safer to retreat into the details of the program, to use complex terms as a form of camouflage. (Button p. 168)

Unfortunately, what we discover reading Watson and then Button is that the status of public language continues to decline. We need to think carefully about their message and act accordingly. As Orwell explained nearly sixty years ago:

Modern English is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble. If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration: so the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers. (Orwell ‘Politics and the English Language’)

The fight against ‘bad English’ should be the concern of all citizens. As history has taught us, those who have control of the public narrative set the public agenda. As those English monarchs knew so long ago, linguistic facility bestows power and freedom.

Referenced works

Blake, Elissa. ‘Michael Gow asks life’s hard questions in his new play.‘ Sydney Morning Herald12 February 2014.

Button, James. Speechless: A Year in my Father’s Business. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2012.

Gow, Michael. ‘Once in Royal David’s City.’ Sydney: Currency Press, 2014.

Johnson, Samuel. Dictionary of the English Language. 1775.

Keating, Paul. ‘Redfern Speech (Year for the World’s Indigenous People).’ Delivered in Redfern Park, 10 December 1992.

Lancashire, Ian. ‘Dictionaries and power from Palsgrave to Johnson.’

Anniversary Essays on Johnson’s Dictionary. Eds Jack Lynch and Anne McDermott. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005: 24–41.

Malouf, David. ‘Made In England: Australia’s British Inheritance.’ Quarterly Essay 12. Melbourne: Black Inc., 2003.

Orwell, George. ‘Politics and the English Language.‘

Watson, Don. Death Sentence: The Decay of Public Language. Sydney: Vintage, 2003.

YouTube sources

Rumsfeld, Donald. ‘Known unknowns!‘

The Chaser’s War on Everything. Season 2 Episode 1.

The Hamster Decides. 2013. Episode 1.

Further reading

Button, James. ‘Fighting the death sentence.‘ The Age 1 November 2013.

Keating , Paul. ‘Funeral Service for the Unknown Australian Soldier.‘ Delivered 11 November 1993, Canberra.

Orwell, George. Nineteen Eighty-Four: A Novel. New York: New American Library, 1961 (1949).

Victorian Council of Social Services (VCOSS). ‘10 years after Don Watson’s Death Sentence: How to give policy language a new lease of life.‘ 6 August 2013.

Watson, Don. Recollections of a Bleeding Heart: A Portrait of Paul Keating PM. Milsons Point, NSW: Knopf, 2002.

—. Watson’s Dictionary of Weasel Words, Contemporary Clichés, Cant & Management Jargon. Milsons Point, NSW: Vintage, 2005.

© Copyright Bernadette Brennan 2014