Essay by Robyn Sheahan-Bright

Fox was a contemporary classic the minute it was published – an extraordinary picture book that has been acclaimed throughout the world for its mastery of words and pictures. It is a breathtaking collaboration by Margaret Wild and Ron Brooks, two of Australia’s most respected writers and illustrators for young people. Together, they’ve created an allegory of heroic proportions that is told in a spare, poetic text and hauntingly arresting illustrations. They engrave on the reader’s heart profound ideas of love, grief, loyalty, desire and redemption.

Margaret Wild’s verse novels and many picture books have been widely acclaimed, with some calling her Australia’s ‘leading picture book writer’. Her first was published thirty years ago, and she seems to have an endless reservoir of stories to tell. She has won the Children’s Book Council of Australia (CBCA) Picture Book of the Year award three times, and been honoured or shortlisted in those awards many times. She was included in the 2000 International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY) Honour List for First Day (Allen & Unwin, 1999), and received the CBCA’s Nan Chauncy Award in 2008 for her outstanding contribution to children’s literature in Australia. She has collaborated with many of the very best illustrators in the industry, including Ron Brooks, on several texts. With Fox, she brings a poet’s sensibility to the writing of a mesmerising and powerful work about the elemental need for companionship in our lives. Her writing bristles with urgent action and sings with suggestive imagery; it is pared back, sometimes playful, and always emotionally resonant. In this way, it carries the very essence of what the story is about – the arcane battle between innocence and evil, kindness and cruelty, love and hate.

Ron Brooks, four-time winner of the CBCA award for his picture books, has also won many international awards, and was the IBBY Australia nominee for the 2014 Hans Christian Andersen Award. His work has always skirted the bounds of what is conventionally expected of a picture book, taking the medium to its extremes. The evocative majesty of his art is very evident in Fox, which won not only the CBCA award but also the Queensland and NSW Premier’s Awards in 2002, and the 2004 Deutsche Jugendliteraturpreis (German Youth Literature Prize). It was also included on the 2002 IBBY Honour List, and it has been translated into many languages. Brooks brings to Wild’s text the visual and intellectual acuity that has distinguished his oeuvre, but takes his insights to a new level in this extraordinary exploration of the underlying forces at work in the narrative. He has read not only the words but the ‘gaps’ between them, and responded with an interpretation that renders the verbal even more powerful. Some double-page spreads are crowded with painful action; others depict empty space that aches with emotion. He has employed the artist’s innate understanding of ‘woundedness’ to create a visual text that adds layers of further meaning to the written.

The story goes… Two damaged creatures emerge from a charred forest destroyed by bushfire. Dog has lost an eye and rescues Magpie, but she doesn’t want to be saved if she can no longer fly with her burnt wing. Dog perseveres, however, and together they embark on a journey, with Magpie on Dog’s back. ‘FLY, Dog, FLY! I will be your missing eye and you will be my wings.’ When the cunning Fox appears, Dog is as welcoming as ever, but Magpie is not so sure of their new companion. ‘Now and again Fox joins in the conversation, but Magpie can feel him watching, always watching her. And at night his smell seems to fill the cave – a smell of rage and envy and loneliness.’ Magpie’s suspicions are overturned by her desire to fly again, though, and she is tempted three times before dangerously embarking on a journey with Fox, only to discover his twisted intentions, wrought by jealousy and loneliness. The existential howl of ‘triumph or despair’ within each of us is evoked in his painful abandonment of Magpie. But not only is Magpie left alone: Fox has alienated himself from those who sought his friendship, and has consigned Dog to solitude as well. And it is the latter who brings Magpie back to engagement with life; the heart-wrenching thought of her friend waking to find her gone. Can Magpie find her painful way home again?

Brooks writes in his memoir Drawn From the Heart (Allen & Unwin, 2010): ‘When I first readFox, I felt as though I had been punched in the chest, very hard, or that I’d been run over by a truck, a dirty great concrete mixer. It hurt. It was horrible.’ Such is the power of Wild’s honest writing, crafted as it is from pure, visceral emotion. She makes no concessions to those who fear that children won’t be able to engage with such a demanding text; and of course, they understand it perfectly. Adults often underestimate the intuitive understanding that children bring to reading, and seek to ‘protect’ them from exposure to complex themes.Fox challenges such prejudices, and its publication acknowledges the importance of mature, emotional investigation in the picture book form. As Brooks further records in his memoir: ‘The truth, at least as far as I’m concerned, has got nothing to do with nice. The best kids’ books aren’t what I’d call nice. Even kids – pieces of sun, pieces of moon, maybe – are not always nice.’ Children take from this text insights based on their own emotional understanding of the world, rather than what adults perceive in a story. ‘They know about the daily hurts and changes of allegiance in their schoolyard, in their street.’

In this stunning work, Wild has used such strong language to embody universal archetypes, and created a work of mythical import for all ages. Fables and folk tales are not only the stuff of child’s play and storytelling, but also of a more adult exploration of the subconscious. The haunting nature of this contemporary tale is a completely new riff on several features that recur in traditional tales. Two companions (Dog and Magpie), thrown together by tragic circumstance (fire), embark on a journey that is interrupted by a meeting with a threatening stranger (Fox). Magpie is thrice put to the test, is finally duped by Fox and then assumes a heroic ‘everywoman’ status in embarking on a new journey home to Dog, which will test both her strength and endurance. By combining the framework of fable – a constant tool for picture book writers and novelists alike – with an inventive plot that is enriched by an open ending, Wild has challenged Brooks to put a new ‘spin’ on the material.

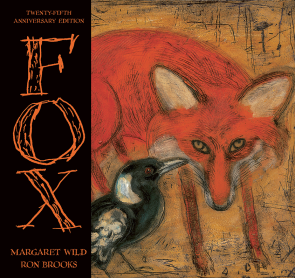

As a result, this spare and elemental narrative is explored in a visual text that is an alchemical mix of several arresting features. Brooks’ skill in design is evident first in the cover, which depicts Fox in full flight across both front and back, in a confronting image dominated by haunted, staring eyes that demand the reader’s attention. His mastery also presents itself in the scratching technique used in the hand-drawn lettering of the text, which echoes the elemental and arcane forces at work here. Brooks said that he decided to painstakingly ‘draw’ the text with his left hand, in a style that mimicked that of a child, because he wanted the reader to have to ‘slow down’ to read the text – to feel ‘Magpie’s discomfort, confusion and pain’. The layout is strikingly inventive, too: some pages are to be read by turning the book on its side. In a large format, he utilises the space in every element of the page and overturns conventions in every aspect of his art. The impasto layering of oil, acrylic and watercolour paint, shellac, and oil sticks is suggestive of a layering of meaning. Using a variety of traditional and non-traditional art tools, he ‘gouged, scratched and scraped’ in order to achieve his desired effect. This engraving of marks on paper results in a rendering of images that is both painterly and childlike, subtle and dramatic.

Brooks’ palette contains the muted hazy colours of the Australian landscape; the ochre colour of the opening endpapers contrasts symbolically with the blue-green of the closing ones. The colours evoke the disparity between the arid desert and the lush gully, where Dog and Magpie make their first home together. After the fire, the land has recovered, and so too have they. In contrast, the vivid red-orange of Fox, who ‘scorches through woodlands’, is symbolic of fire and the terrible damage it visits on nature. He also serves to denote that what we envy in others, we often seek to destroy. But fire, of course, is also responsible for regeneration, and this idea is very much at the forefront in this brilliant work.

Anthropomorphism in children’s books is always a tenuous art, and here Wild and Brooks handle it in both the verbal and visual texts, with the cool command of character and voice for which they are both renowned. There is a stark cruelty but also a desperate emptiness in the eyes of Fox as he is depicted on the cover, which reflect a haunted character hewn from nature’s forces and capable of self-destructive action in order to survive. In contrast, Dog is affably kind – perhaps naively so – and Magpie is lively despite being aggrieved by her loss, and moves with a ‘jiggety-hop’ to her step. Both are depicted in an endearingly ‘human’ way. Magpie’s temptation by Fox, though, is also indicative of human frailty, and the story is never one-sided, nor are the characters stereotypical. As Brooks has written: ‘There is so muchpain, for both of them.’ Fox is no villain, and nor is Magpie any type of saint. Fox has been damaged, and seeks to damage in return.

A successful picture book is a work that allows space for text and image to expand on each other; to extend and elaborate on what each can say on its own. This delicate duet is more than the sum of its parts, and in Fox we witness two creators perfectly in step with their material, evincing abundant faith in each other. Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge the context in which this book was published. Australia has become highly respected for the sophistication of its picture books, illustrated by luminaries such as Armin Greder, Shaun Tan, Ann James, Jan Ormerod, Jeannie Baker, Freya Blackwood, and Bob Graham. But it was not always so, and Brooks was arguably the progenitor of their success with his groundbreaking works The Bunyip of Berkeley’s Creek (Penguin, 1978) and John Brown Rose and the Midnight Cat (Penguin, 1980), both written by Jenny Wagner. Until the 1970s we had no picture book industry to speak of, and the sophistication of Brooks’ work provided an exemplar of what could be achieved. Some thirty-five years later, he is still setting the tone and pace for others.

Fox is a landmark picture book in the canon of Australian children’s literature. Having read this book many times, what stays with me is the painful jolt it gives to the reader’s perception, leaving you with both a haunting sense of loss as suffered by the lonely and bitter Fox, and of the restorative joy found by Dog and Magpie in their care for each other. It demonstrates the skills, talents and bravery of its makers, who took risks in producing a work of such innovative design, and in dealing with such sophisticated and challenging subject matter. And it is a testament to the power of the art of picture book collaboration, to its ability to speak volumes about the essential questions of humanity. It does, in a condensed, poetically attuned and refined space, what a novel does in a more expansive one. Wild and Brooks have spoken to their readers from the deep well of their creative wisdom and talent, and created a story that is truly unforgettable.

Further reading

Brooks, R 2010, Drawn from the Heart Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest.

‘CBCA Judges Report 2001’, Reading Time, vol. 45, no. 3, p. 10.

Doonan, J 2000, ‘Drawing on the Text: the Art of Collaboration ’ in Anstey, M & Bull, G (eds.),Crossing the Boundaries, Pearson Australia, Sydney, pp. 17–31.

Holden, S 2001, ‘Picturing Books Ron Brooks: The art of illustrating Part One’, Educare News,May 2001, pp. 34–7.

Holden, S 2001, ‘Picturing Books Ron Brooks: The art of illustrating Part Two’, Educare News,June 2001, pp 39–42.

Hunter, L 2000, ‘Fox written by Margaret Wild, illustrated by Ron Brooks: Linnet Hunter looks at a publishing landmark’, Magpies, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 4–6.

Reeder, SO 2004, ‘Developing a Hungry Eye: Evaluating the Visual Narrative in Australian Children’s Books’, thesis, University of Canberra, Canberra..

Sorensen, M 1992, ‘From the Word Go: Books for Younger Readers’, Australian Book Review, no. 145, pp. 68–72.

© Copyright Robyn Sheahan-Bright 2014

(3 votes, average: 3.67 out of 5)

(3 votes, average: 3.67 out of 5)