Introductory activities

Stasiland presents the story of German reunification through a re-presentation of personal experiences drawn from interviews and research undertaken by Anna Funder. In the context of the fall of communism, and with a focus on the role of the Stasi in the lives of East Germans, Funder confronts the reader with characters traumatised by the past and dislocated in the present. Narrative itself provides a human strategy for understanding time, process and change and this is particularly evident in this text. Funder presents her text in a hybrid genre, that of literary journalism, where she combines the power of facts with the craft of fiction.

Literary journalism enables us to appreciate the ways that stories help us understand the world in which we live and give us insights into human experience. This genre dramatically recreates the observable world of real people, real places and real events with the storyteller acting as the mediator of reality.

By way of introduction to the text students will engage in activities where they:

- consider metaphors associated with detente

- develop their understanding of the historical context to Stasiland

- reflect on the ways in which literature plays witness to history.

Activity 1: Inner borders and other metaphors

In this activity students analyse and create linguistic and visual metaphors associated with post World War II Germany.

- Display for students the three images below and the following phrases. Phrases: inner border, cold war, iron curtain and missile shield.

|

|

| Image 1: East German BT-9 border watchtower at Point Alpha, Thuringia. |

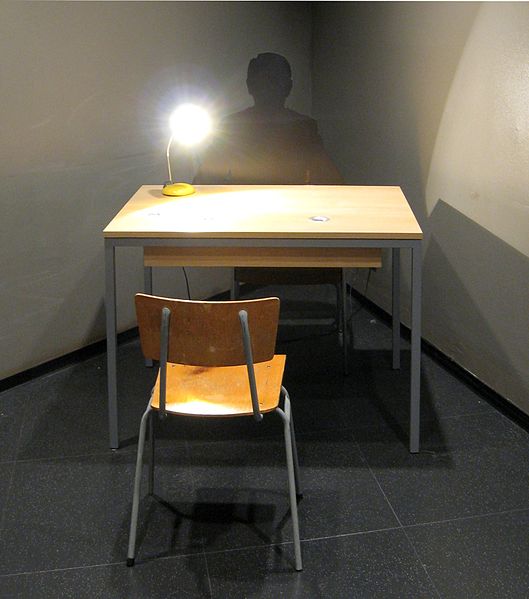

Image 2: Stasi interrogation room, Berlin museum. |

|

Image 3: Hohenschoenhausen prison.

These images have been licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

- Using the phrase missile shield as an example, illustrate for students, by way of a diagram, the paradoxes implicit in this metaphor: define the concept of a shield, name its properties and relate this to the action of a missile. Students should see the incongruence suggested in the metaphor of the shield when used in this context. Likewise, model for students how to create a metaphor based on one of the images.

- Explain to students that metaphors, visual and linguistic, generate uniquely personal images in readers’ minds.

- Working independently, students:

- create a mindmap of the meaning of the remaining phrases that illustrates the force of the metaphor and its possibilities, nuances and ironies

- generate metaphors based on the remaining images and share and test their effectiveness with fellow students.

Activity 2: The promise in the title: Stasiland

In this activity students examine the nuances of the title, Stasiland, and share their responses to it on a class blog.

- Explore with students possible meanings of the title and what it might suggest. The word land suggests sovereignty and territory, a defined political space. According to the Oxford dictionary the word stasi is an abbreviation of the German, from Sta(ats)si(cherheitsdienst) meaning the internal security service of the former German Democratic Republic, abolished in 1989. In the Collins dictionary it records that the stasi are the secret police. Discussion starters might be:

- What are the possible nuances of the title?

- Do you think the title positions the reader to respond in a particular way?

- What promise does this title offer you?

- Students navigate to the author’s website and explore the range of book covers forStasiland in the gallery. They select the covers that they think best capture the promise in the title. Students could also reflect here on the significance of the country of publication and its impact on the cover.

- Direct students to upload their contributions to the blog.

(ACEEN001) (ACEEN028) (ACEEN031)

Rich assessment task 1 (productive)

Activity 3: What if your homeland disappeared?

Prior knowledge of circumstances that led to the division of Germany and the construction of the inner border and the Berlin Wall can be gained through previewing a number of online resources. Students might like to reflect on how an individual’s homeland could be seen as disappearing at both the time of the division of Germany and at the time of reunification forty years later. In this activity students research the historical context, selecting photographs that represent critical moments in history for inclusion in a photo essay entitled: What if your homeland disappeared?

- Prior to the research, explain to students some considerations for the creation of a photo essay:

- an evocative title (in this case, given to them)

- a lead photo that provokes an emotional response in the audience

- an opening and closing paragraph that contextualises the essay

- whether it is narrative or thematic

- the range of photos such as panoramic, close-up, detailed, portrait

- the order of photos: for example, a lead photo, a contextualising photo, a portrait, a photo of detail, a summative final photo

- six photographs with captions – no more than 150 words

- photos work with rather than against the written text in the photo essay.

- Divide the class into two groups. One group will research the division of Germany, the second its reunification. Allocate to the two different groups a series of websites to use for research (see table below).

- Distribute the focus questions below to students:

- What have you learned from your research about how borders affect humanity?

- How do people respond when their homeland disappears?

- In small groups, student responses are combined into a photo essay. Groups should have six students with a balance of those students who have researched the division and reunification of Germany. Photo essays could be published in a range of places: class wikis, blogs, classroom presentation, prezis, Powerpoint, tablet apps such as Explain Everything.

(ACEEN011) (ACEEN012) (ACEEN013) (ACEEN016) (ACEEN018)

Personal response on reading the text

Empathic reading of literary non-fiction texts adds a particular dimension to literature teaching: students are invited to empathise with real experiences of other people.

Prior to reading the text, teaching approaches could include activities where students:

- Name the effects of key experiences in their lives that may have left a mark.

- State two or three themes that emerge from the marks they carry.

- Devise provisional topics for stories based on these themes. These topics could project into other contexts and situations. (Adapted from Michael Rabiger’s Directing the Documentary. 2nd ed. Elsevier, 2004.)

During reading teaching approaches enable students to appreciate how narrative has the power to build empathy and a deep understanding of the ‘other’. Beginning with reading students into the text, teaching approaches could include:

- reading aloud in class the opening chapters of Stasiland and using personal triggers to stimulate engagement such as:

- Have you ever been in a place that doesn’t exist?

- Why do you think the author was so instinctively drawn to Miriam? Have you ever been instinctively, compellingly drawn to someone else’s story?

- devising the interview questions that could have led to a particular chapter

- mapping the locations and journeys of the characters on a large map of East Germany

- selecting the most important word/line/image/object/event in the chapter and explaining your choice.

After reading learning activities could include:

- conducting a conversational roundtable where students analyse how the author investigates an aspect of the texts such as character, place or aspect of life – for example surveillance

- compiling a comparison chart that explores how Stasiland sheds light on underlying truths about human experience that remain relevant in the 21st century

- debating whether the author is successful in portraying a truth ‘beyond the important facts of the world’ (Christa Wolf, German novelist and literary critic).

Outline of key elements of the text

Stasiland is the result of a series of interviews undertaken by Anna Funder after the fall of socialism and the reunification of Germany. The text contains a series of individual accounts of experiences with the Stasi including those who were perpetrators and those who felt its consequences. Accounts of persecution – suffered by the characters Miriam, Julia, Charlie and Frau Paul – are interwoven with the perspective of the perpetrators of persecution, people inured to evil to different degrees: Herr Winz, Hagen Koch, Karl-Eduard Schnitzler, Herr Bock. The story of Miriam and the author’s empathic desire to resolve the unanswered questions around Charlie’s death operate as a refrain throughout the text. Miriam’s experience shows how injustice, surveillance and submission to authority shapes identity and, in some cases, fractures lives.

The writer’s craft and close reading

In this learning sequence students engage in a series of close study workshops. As workshops these activities are framed by the investigation of a specific stylistic focus and involve independent and group-dependent components.

Workshop: Critical analysis of the language of the text

In this workshop (based on this approach to close study) students closely analyse an extract from Stasiland. Close reading requires students to understand how the meaning of the extract is conveyed through its linguistic, semantic, structural and cultural qualities.

- The workshop begins with a provocation to use as class discussion:

- PROVOCATION: Who is Julia and why should we care?

- In responding to this question students could consider the narrative detail they have gleaned about her life experience, her personality, the dialogue included to represent this character.

- Explain to students this four lens strategy for close study. These four lenses are useful to deconstruct texts but they must be seen as interrelated for students to engage in effective close study.

| The linguistic lens pays attention to: | The semantic lens pays attention to: | The structural lens pays attention to: |

The cultural lens pays attention to: |

|

|

|

|

| These first two lenses might be seen as more accessible to students. Here students often describe a particular textual element and its relationship to meaning and its nuances. | These lenses tend to be more analytical and interpretive. Students assess and judge how parts of the text relate to each other and to other cultural material outside the text. | ||

- As a class read an extract from Stasiland. It is the section in the text immediately after Julia has confided to the author that she has been raped – read from ‘A cigarette sits forgotten in the ashtray’ on page 143 to ‘In some kind of cosmic penance, I spend the day in bed’ on page 145.

- Instruct students to read this extract a few times noting aspects which create the extract’s literary quality.

- Divide the class into groups of four allocating each student one of the four lenses to use as a focus on the extract. Students share and classify their initial annotations and then, in groups, generate some more observations about the extract by using the four lens strategy.

- Groups present their observations, with supporting evidence, to the class. A Venn diagram could be a useful aid here.

(ACEEN002) (ACEEN004) (ACEEN005) (ACEEN022) (ACEEN024)

Workshop: Characterisation

Through characterisation in texts we gain insights into human experience. This workshop is an imaginative recreation activity that focuses on exploring the characterisation of real people, from real places experiencing real events in East Germany. It draws on Paolo Freire’s work as portrayed in Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed.

- In groups students write a scenario based on a personal story of oppression from one of the interviews in Stasiland.

- Each group dramatises this scenario for the rest of the class and, as a class, discusses the oppression, the oppressed and the oppressors.

- The group then performs the scenario again but this time students from the class are asked to physically intervene in the drama and change the scenario by being one of the characters in the story. This intervention allows students to empathically appreciate the oppression and reminds them of the need for social action.

- As a follow-up activity students write an analysis of the character’s experience in Stasiland reflecting on how their difficulties might be redressed.

Another workshop focusing on characterisation might focus on a shared-reading approach. This activity is an activity based on Sheridan Blau’s The Literature Workshop. In this activity students engage with the detail of the text to analyse character.

- Select a section of the text for students to analyse, for example dialogue involving Hagen Koch, Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler or Frau Paul. Students read that section for five minutes in silence. They highlight sentences relating to character that they find confusing, interesting or disturbing.

- A second reading of the text now occurs. This time students engage in jump-in reading. The class reads around the room changing readers by jumping in when a sentence or word or phrase is powerful, confusing, interesting or disturbing. Students annotate their text, but do not share any comments or interpretations.

- A third reading involves students reading aloud in a random, non-linear way the sentences that are significant to them.

- After the three readings, students select a sentence that they think is significant. They write about that sentence for several minutes.

- Students meet in groups of three to read and refine what they have written about the chosen character before sharing the observations about that they may have found confusing, interesting or disturbing with the class.

(ACEEN001) (ACEEN008) (ACEEN009) (ACEEN018) (ACEEN027) (ACEEN029) (ACEEN040)

Workshop: Narrative perspective

In this workshop activity students reflect on the relationship they, as readers, develop with the narrator in the text. They reflect on the role of the narrator in non-fiction texts.

- Begin the workshop by asking to students to consider what they expect the role of the narrator to be in a non-fiction text. How visible do they expect the narrator to be in the text? Students could also make a list of the personal characteristics of the narrator.

- In pairs students discuss, analyse and find evidence for responses to the following points:

- whether there is a moral position from which the events are viewed

- whether there is a consistent point of view from which the events are evaluated

- whether the narrator presents a non-contradictory reality

- whether and why (or why not) the narrator draws attention to herself

- whether the reader’s response is affected if the author intrudes on the narrative

- whether the narrative perspective reflects dominant discourse

- whether students, as readers, are resistant to the text’s perspective.

- Provide students with a copy of Malcolm Knox’s essay on the text. In pairs compare his assessment of the text and the role of the narrator with their responses.

(ACEEN004) (ACEEN008) (ACEEN009) (ACEEN024) (ACEEN029)

Workshop: Structure

In this workshop students analyse the text’s structure through a ‘proximate reading’ strategy. This is outlined in the following sequence. Structure can be seen as referring to the arrangement, network or patterns of connection that underlie a text and shape its meaning and its readers’ response.

- Remind students that a text’s structure might be organised around:

- chronology: order and time

- cause and effect

- problem and solution

- parallels and contrasts

- binary opposites based on gender, political perspective, belief, ideology.

- Individually students consider the following questions:

- As you read the text were you aware of any of these structures?

- What were the elements of these organisational structures?

- How did these structures guide your reading of the text?

- Which of these most shaped your response to the text?

- Focusing on the structure in the text that they found most significant, instruct students to select two short extracts from the text. The first extract is the extract that they find to be the most important; the second extract is one that foreshadows it. Students record the first one or two lines of each extract and the page number on separate cards.

- Students then convene in groups according to the structural aspect they have chosen, eg chronology, or gender and so on. Students order the cards according to the text itself and read aloud the whole text from this stance.

- As a class discuss the interpretive differences that readers may adopt when responding to a particular text structure.

(ACEEN004) (ACEEN005) (ACEEN018) (ACEEN019) (ACEEN024) (ACEEN028) (ACEEN036)

Workshop: Forming judgements about a text

This workshop is a synthesising activity that aims to elicit personal and diverse judgements on Stasiland. Students form focal judgements about the text.

- Students select one word that they think is crucial to the text. They make a wall of these words for display in in the classroom. Students examine how they relate to the title.

- Students select the most crucial passage in the text. To do this students:

- note several short passages that capture the central concerns of the text

- review this bank of passages and select the single most significant passage

- reduce this passage to a three or four word phrase that captures the entire text

- display the passage and the phrase in the classroom.

- Students select the most important aspect of the text making notes that justify their choices through close reference to the passages that have been identified.

- Students then devise an essay question based on this phrase and write a personal response essay to their question.

Comparison with other texts

In this activity students explore and reflect on different ways of reading texts. Students learn that authors and readers do not read and create meaning in isolation just as we do not live in isolation. The relationship between authors and readers is dynamic, interactive and shaped by the contexts that frame it. In this sequence students will question the ideologies underpinning a range of texts related to East Germany and explore the ideologies and possible critical perspectives that can shape our appreciation of Stasiland.

In this learning sequence students consider their initial response to the text and how it may have developed. It incorporates a wide reading activity that encourages comparison and critical reflection of texts.

Activity 4: Reflection

Instruct students to recall their initial impressions of Stasiland. Discussion prompts might include:

- In what ways was the class view different from yours?

- What were some things you noticed in discussion that you didn’t notice before?

- What seemed to be important after close study that didn’t come through in your initial reading?

- Archetypes often play a critical role in texts. Describe how characters, plot, and theme in Stasiland could be viewed in archetypal terms. For example, is this a classic story of good versus evil? (Adapted from Appleman, D. Critical Encounters in High School English: Teaching Critical Theory to Adolescents. 2nd ed. Teachers College Press, 2009.)

Activity 5: The one minute paper

In groups students preview the following texts and each decide on one text for closer study at home. The texts listed below cover a range of textual forms and perspectives on how individuals responded to their lives in East Germany.

- Opening to a novel: Christa Wolf’s One Day in the Year

- Poetry anthology at the Voices Compassionate Education website

- Film: The Lives of Others (directed by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 2007

- Documentary: The Wall (original title Die Mauer, directed by Jürgen Böttcher) 1990

- Film: Goodbye Lenin (directed by Wolfgang Becker) 2003

- Museum: Stasimuseum Berlin

- Museum: Wende Museum

(ACEEN001) (ACEEN009) (ACEEN019) (ACEEN021) (ACEEN029)

Activity 6: Collaboration and analysis

Reconvene the groups so that the determiner is the text – students who have presented one minute papers on the poetry anthology group together, the novel opening group together and so on. In groups students discuss the selected text using questions such as:

- How does this text relate to your own time and place?

- What ideologies are represented in the text? Does the writer have a preference?

- Do you see the world differently to the author?

- How do women and men feature in the text? Does gender play a role?

- Gaps and silences: which people in society are represented as central, under presented or misrepresented?

- Are there binary opposites at play in this text – for example men/women, aggression/submission, individual/society, order/disorder, privacy/surveillance, regime/democracy?

- Does the text comment on itself? Does this shape your response as a reader/viewer?

In groups students combine these answers into a poster or chart about the text and its perspectives.

(ACEEN038) (ACEEN039) (ACEEN040)

Rich assessment task 2 (receptive)

Activity 7: Evaluating the text in a letter-essay

Throughout this unit of work students have undertaken a range of reflecting and evaluating activities. This activity is a synthesing activity that focuses on the combining of facts and personal voice, a binary that underpins study in this unit. One way of evaluating this is a letter-essay.

Nancie Atwell in The Reading Zone proposes the letter-essay as a form of textual evaluation. In this activity students write a letter-essay that draws on the sweep of learning activities undertaken in the course of their study and send it to a fellow student or the teacher as an evaluation. The recipient then responds in a paragraph response. Some key points about this process:

- The purpose of the letter-essay is to reflect on the book, the reading, the author and their writing.

- Each letter-essay should be at least two pages long and written as a personal, critical response.

- Students should include at least one passage that shows something essential in terms of how they reacted to the book’s concerns, character development, plot structure, or the author’s style.

- Students pose their ruminations – questions about the author, the characters, the structure, the voice, the critical perspectives and themselves as readers.

- The letter-essay includes comment on the significance of this text as an example of its genre, its cultural context and relevance.

(ACEEN014) (ACEEN018) (ACEEN019) (ACEEN032) (ACEEN033) (ACEEN034) (ACEEN035)

Activity 8: Hypotheticals

In this activity students apply skills of critical analysis to Stasiland. Using an imaginative recreation scenario such as a symposium titled ‘Writers’ Hypotheticals’, students present hypotheticals to an imagined Anna Funder.

- To prepare for the symposium students apply the questions from the previous activity (Activity 7: Collaboration and analysis) to Stasiland.

- Based on this analysis students create their own hypothetical questions. Remind students of some of the aspects of the text covered in the study so far:

- the metaphors of inner borders

- the significance of a homeland to identity

- the tragic consequences of injustice

- interplay of authority and identity

- fractured identities

- stylistic elements such as characterisation, narrative perspective

- representations of similar concerns in other text.

- Sample hypotheticals might be:

- Your manuscript has been rejected by the publisher because it is regarded as too damning about the Stasi and there is sympathy for them in Germany. You have been asked to modify the balance by rewriting some chapters or including new ones. How will you respond?

- Concerns have been raised that your representation of the complexities in East Germany draws too strongly on the heroes and villains binary. Has there been an over-simplification?

- Remind students of features of hypotheticals such as:

- use of the second person

- the creation of a contextualised situation

- the requirement of a question that prompts an extended response rather than a short answer

- the potential to reference perspectives encountered in their wider reading.

- After the creation of the hypothetical questions students enter these for peer review and checking.

- Role play the symposium.

(ACEEN002) (ACEEN008) (ACEEN009) (ACEEN010) (ACEEN011) (ACEEN014) (ACEEN028) (ACEEN030) (ACEEN032) (ACEEN034) (ACEEN040)

(7 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(7 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)