Introductory activities

A note on engaging with contentious issues

Engaging students with contentious issues and modelling appropriate ways of framing understanding and participating in debate can be of benefit. Indeed, the General Capabilities of the Australian Curriculum invite teachers to delve into this territory, within the Critical and Creative Chinking, Ethical Understanding, and Intercultural Understanding capabilities.

It may be helpful to set out a contract of expectations before engaging with the study of the issues presented in this unit. All members of the learning community should work together to generate this contract, the detail of which may evolve from class discussion led by the teacher, or by students working in small groups. The exact format of this activity will depend on the previous experiences and relationships established between students and the teacher.

It is suggested that this contract centre around:

- Safety (we should be safe to express our opinions)

- Respect (for the individuals affected by this issue, and for each other in presenting opinions)

- Listening politely (structures may be put in place to facilitate this)

- Valuing diversity (appreciating that all experiences and views contribute to a cohesive whole)

Pre-reading: how diverse is your universe?

In this game-oriented activity, students are invited to consider their own cultural background and identity, and question the interactions that they have in their daily lives.

Materials

- 1 plastic or paper cup (per student)

- Coloured beads or icy pole sticks

Process

This activity can be conducted as a whole class or in smaller groups (e.g. table groups). Students are seated in a circle, each one starts with an empty cup. The supply of beads or icy pole sticks is placed in the middle of the circle. The teacher explains that each colour represents a different cultural background (for example, Anglo-Australian, other European, African, American, Middle Eastern, Asian, etc.). The exact categories elected will depend on the cultural backgrounds that comprise the school and local community.

The teacher reads a number of statements, and the students select a colour to show their response, placing their beads or icy pole sticks into their cups. The statements are:

- Pick the colour that best represents your own cultural background

- Pick the colour that best represents each of your parents

- Pick the colour that best represents your closest friend

- Pick the colour that best represents the last person that you interacted with outside of school and not in your family

- My neighbours (at home) on either side are …

- My GP is …

- My dentist is …

- My school principal is …

- The people in my social circle are mostly …

- The author of the last book I read was …

- In the last movie I saw, the people were mostly …

- The people in my favourite TV show are mostly …

- My favourite food comes from …

- The person I most admire or who has had the biggest impact on my life is …

- My favourite musician or band members are …

After the teacher has read all the statements and the students have filled their cups, they are asked to look in their cup and describe what they see. The teacher may ask the students to write a paragraph of reflection in response to this activity.

NOTE: This activity was adapted from the resource found in the Diversity Resources Activity Guide.

A great complement to this activity is the SBS Census Explorer. Using this online interactive, students can discover how diverse their suburb or town is, in categories including ancestry, age, food, religion and birthplace. This could be used in classroom activities to generate discussion or in more depth. Students may summarise or graph the data pertaining to their suburb of residence, providing ample scope for links to the numeracy capability and cross-curricular inquiry in Mathematics and Geography.

Pre-reading: class discussion and mind map

Using the stimulus material of the UNHCR ‘Spot the Refugee‘ poster (p. 3), students complete an analysis of its message. A thinking routine such as Think, Puzzle, Explore or See, Think, Wonder may help students organise their thinking.

In whole class discussion, ask students to think about the message the poster is trying to convey? What kinds of persuasive techniques can they identify? How is the language used to position the audience (e.g. ‘they have nothing‘; ‘refugees are just like you and me‘).

What are some of the reasons to value cultural diversity? What advantages does a culturally diverse community offer us? Summarise the students’ thoughts using a whiteboard or interactive whiteboard/touchscreen. If students are equipped with 1:1 technology, they may summarise the mind map using an application such as Bubbl.us or Popplet.

(AC9E7LA03) (AC9E7LY03) (AC9E7LY04)

Pre-reading: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child

This activity is particularly suited to stronger groups of students and not all activities are essential to the unit. Undertaking this activity should be based on the teacher’s judgement.

Exploring the UDHR and the CROC at this stage of the unit should provide students with the necessary background and context for later activities concerning an evaluation of the treatment of Mahtab and her family.

Start by brainstorming the following questions:

- What does it mean to be safe?

- What do you need to be safe, healthy and develop to your full potential?

- How can we protect the rights of people – adults and children – to be safe?

Then students will work collaboratively to determine their final lists. Using the Multiply and Merge co-operative learning strategy, they will individually list eight things that are needed to be safe, healthy and develop to your full potential. Each student will then pair up with another student, needing to reduce lists of 16 back to eight, reaching consensus on what is common, what to keep, and what to discard. They will then join with another pair and repeat the process. Each group of four will then report back to the whole class, in order to generate a final list of eight.

The students may then explore the agreements in more detail, with close guidance from the teacher. There is a simplified version of the CROC. There are also a number of useful videos on YouTube, produced by reputable organisations such as UNICEF and Amnesty International, such as ‘What Are Child Rights?‘ and ‘Everybody – We are all born free‘. There is also an excellent picture book about the UDHR, also titled We Are All Born Free.

When students have learnt more about the CROC and the UDHR, they may be asked to complete the Colour-Symbol-Image Thinking Routine, either individually or with a partner, to show their understanding. The CSI routine requires students to determine a colour, symbol and image that best represent the idea or concept they are exploring – in this case, ‘human rights’.

A visual display of student responses to this activity, including their lists of rights and the CSI representations, would be a powerful thinking prompt as they progress through the unit.

(AC9E7LY02) (AC9E7LY04) (AC9E7LY05) (AC9E7LY06)

Personal response on reading the text

Analysing the title and cover

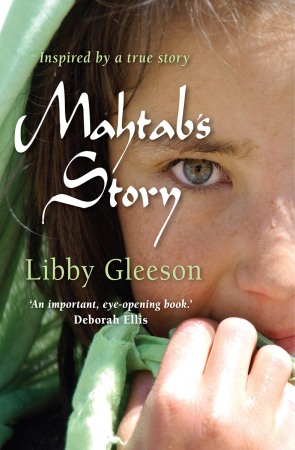

From the outset, we are positioned to view the subject of this story as an ‘other’. The image on the cover shows a partially-obscured face, which seems to be covered by a ragged green headscarf. There is a bead of liquid (sweat?) on her nose, and her visible green eye stares intently at the reader. We are informed by the title that this is ‘Mahtab’s Story’. The reference in the third person to the protagonist, whose name may be inferred to be of Middle-Eastern origin. Students may use the the cover analysis worksheet (PDF, 275KB) to make observations about the title and front cover.

(AC9E7LA07) (AC9E7LE01) (AC9E7LE02) (AC9E7LE04)

Reality and fiction

The cover tells the reader this is ‘inspired by a true story’. By blurring the line between reality and fiction, the author succeeds in gaining the reader’s sympathy for Mahtab throughout the story. Ask students, as readers, do they prefer reality or fiction? What are the conventions of stories that are based on reality? What are the conventions of stories based on fiction?

As they progress in their reading, the teacher may generate discussions regarding the veracity of the accounts given in the text, their plausibility and reliability. At this stage, students could compare the fictional accounts in the novel to other non-fiction texts about comparable refugee experiences, to make their own judgements.

This may lead to some discussion of the ethics of an author presenting a fictional narrative which takes licence with the lived experience of others. Recent literary debate in Australia centres on the rights of authors to write about experiences outside their own realm of experience and cultural identity, and these questions are worthy of inquiry. Articles such as Ariella Van Luyn’s ‘Lionel Shriver and the responsibilities of fiction writers‘ may be a starting point for teachers wishing to inform their own thinking on these issues.

Plot and location tracking

As students read the book, they should be encouraged to track the plot development and locations represented within the narrative. This could be done using Google Earth. Students should be encouraged to make links between the different locations in the novel and Mahtab’s state of mind and relationships as she undertakes her journey.

Outline of key elements of the text

Summary

Publisher Allen & Unwin has produced an extensive set of teacher’s notes, including a summary of the plot.

Character

The protagonist of the novel is a young girl named Mahtab. As the plot progresses, Mahtab must increasingly call upon her inner resourcefulness and bravery to endure the difficulties she faces. Other characters in the novel include Mahtab’s siblings, Farhad and Soraya, her parents and extended family, as well as her best friend Laila. Later in the unit, there are activities that involve students reflecting on character after a close reading of the text.

Themes

Themes of the novel include:

- Refugees and asylum seekers

- Bravery and resilience

- Family bonds

Rather than outlining these themes to students from the outset, an inductive strategy may be used in the classroom, whereby students explore and analyse the ideas emerging through their reading.

A useful thinking routine for uncovering ‘big ideas’ is Generate, Sort, Connect, Elaborate. In this activity, students work in groups to initially brainstorm all ideas they think have been presented in the work. They then sort the ideas by positioning them on a graphic organiser, with the central ideas in the middle, and the more abstract on the outside. Connections are made between ideas, before students elaborate on and explain the ideas they have generated. At this final stage, the teacher may require that students provide quotes and evidence from the text.

Chapter questions

A set of chapter questions (PDF, 125KB) has been developed for those inclined to use these to support and monitor student progress through the text.

Another approach is to have students write their own comprehension questions. Assign students a chapter each (there are 14 chapters and an epilogue). Have them write three to four questions for their assigned chapter. The number of students allocated to each chapter and the number of questions they produce will depend on the class size. Students can send their questions to the teacher, who may then collate them into a Word document for redistribution. Alternatively, the teacher may wish to use an online tool to construct a quiz using questions, such as those provided by Kahoot or Socrative. It should be noted that Kahoot allows live participation and multiple choice responses, whereas Socrative allows short answer responses and the teacher can produce a report of student responses.

The writer’s craft

Structure

The structure of Mahtab’s Story advances in a linear sequence, following the protagonist and her family as they journey from danger toward their final destination of Australia. At the start of the story the linear structure is somewhat altered, in order to present to the reader a scene from Mahtab’s family’s escape, and the harrowing truck ride over the mountains and out of Afghanistan. Intertextual references, such as memories of home, and the repeated predictions about what life will be like in Australia, are used to reinforce the story’s ideas as it develops. The use of symbolism and motifs such as ‘fog’ and folk tales bring cohesion to the narrative.

Class activity

When reading of the novel has been completed, students may engage in a plot mapping activity. Using the Chalk Talk thinking routine, a long single sheet of butcher’s paper could be used, with students adding sticky notes detailing plot events and rearranging them in the correct order. Alternatively, the teacher may wish to use the provided summary of plot events (PDF, 100KB), which the students can arrange into the correct order.

Students could then be introduced to the ‘Hero’s Journey’ plot sequence. There is a brief animated video available on Vimeo which introduces this structure. Using the larger plot map, students may then trace the events in Mahtab’s Story and correlate them to the hero’s journey blank template.

Finally, by breaking into smaller groups, students could be assigned one stage of the hero’s journey, and produce a ‘comic strip’ summary of that stage in the novel, using a tool such as Storyboard That. Storyboard That has also developed a teacher resource for incorporating the hero’s journey with the resources available on its site.

These activities provide a sound basis for the Digital Storytelling task that forms part of this unit. If timing is a concern, the first part could be undertaken without the elements that follow.

Approach to characterisation

As a text with a child narrator, students can readily relate to some of the concerns presented. In a realistic way, Mahtab vacillates between a maturity beyond her years, along with dejection and insolence. In taking responsibility for her younger brother and sister, she is able to set aside her own feelings and fears, in an effort to comfort and distract them.

Character webs

Each of the characters presented offers a different lens and way of appreciating the events that take place in the story. To develop an understanding of the characters in Mahtab’s Story, the class may be divided into small groups to produce a summary of their assigned characters from the following list:

- Mahtab

- Mahtab’s mother

- Mahtab’s father

- Farhad

- Soraya

- Hamida and Ahmad

Groups may use the character web handout (PDF, 269KB), or another suitable template for documenting their thinking.

(AC9E7LE02) (AC9E7LE03) (AC9E7LE05)

Setting

The setting alters several times during the narrative as Mahtab and her family progress on their journey towards Australia. Each setting is represented with powerful imagery and language, and the differences between each setting and Mahtab’s home in Afghanistan are emphasised.

Word cloud ‘poems’

This optional activity may be conducted individually or in groups. For each setting presented in the novel, students should find all of the adjectives that they can to describe this setting. Using a word cloud generator, they should then produce a ‘poem’ using these words. They need to be mindful that the more times they enter the word in the web tool, the bigger it will display in their resulting image. They should therefore make the location appear in a large font by repeating it the most times, and the adjectives to describe it of varying size, depending on their relevance.

The locations presented include:

- Afghanistan

- Pakistan

- Malaysia

- Indonesia

- Australia (detention centre)

- Australia (outside detention centre)

This activity will develop students’ understanding of specific language choices and how these might be incorporated into their own poetry.

(AC9E7LE05) (AC9E7LE07) (AC9E7LY03)

Use of parallels and contrasts

‘In Australia we will not have to stay inside all the time. You, Farhad, will play football whenever you want to and girls too can play. No one will tell us that we must be quiet all the time. We will all go to school and play games, new games too that we don’t even know of yet …’ (p. 60)

One contrast that is used throughout the story is the juxtaposition of the family’s current situation with their imaginings of a life of safety, security and abundance in Australia. As the perspective shifts between reality and imagination, the reader is provided with an appreciation of how the normalised aspects of their own experience seem so desirable to an asylum seeker child like Mahtab.

The use of folk tales also contrasts with the family’s predicament and provides a narrative framework for the family to make sense of their experiences (e.g. ‘He could be like Sinbad, wrecked by whales or giant waves’, p. 62). The return to the folk tales and old songs as a source of comfort acts as a way of helping the family see hope and practise resilience.

Exploring folk tales

Students in Australia come from diverse cultural backgrounds. As an optional homework activity, they may be asked to explore and find a folk story that relates to their own cultural heritage. This might be a personal story from their own family, or a more widely known folk tale or fairy tale. Students can share and reflect upon the stories they source for this activity.

(AC9E7LE01) (AC9E7LE04) (AC9E7LY03)

Exploring contrast in poetry

A contemporary poet known to work with parallels and contrasts is Brian Bilston. His poem entitled ‘Refugees‘ tells a remarkably different story depending on whether it is read from beginning to end or vice versa. Students may be introduced to this poem as part of their thinking about refugee and asylum seeker issues. Stronger students may be invited to construct their own contrast poem (it is very challenging!).

Read the poem through from the start to the end and then from the bottom to the top.

NOTE: Room on our Rock* by Kate and Jol Temple, illustrated by Terri Rose Baynton, can also be read from front to back or back to front.

* Reading Australia title

(AC9E7LE04) (AC9E7LE06) (AC9E7LE07) (AC9E7LY03) (AC9E7LY04) (AC9E7LY06)

Point of view

The story is told in the third person and presents the events as they relate to the protagonist Mahtab. The thoughts and feelings of the other characters are presented as Mahtab experiences them, and the reader is not aware of information that Mahtab does not know, such as her father’s whereabouts or where they are being taken, when they travel by coach to the detention centre. The effect of this perspective is that the reader discovers plot events at the same time as they unfold for the protagonist, and any extra insight is gained only through inference. This perspective is very effective in creating a sense of empathy within the reader. Students may brainstorm other stories that they are aware of with a similar narrative perspective.

Voice

The voice of the narrator is appropriate to the child protagonist and the young adult reading audience, and the language employed is consistent with this. The narrative voice changes throughout the story to reflect the events taking place, and structure and syntax are manipulated effectively to convey emotion. Some of the previous chapter questions (PDF, 125KB) relate to this manipulation of voice, as it is very effective in shaping the reader’s perspective.

Language and style

There are three main elements of language and style that students can reflect upon:

- Figurative language, including similes, metaphors, imagery and personification

- Syntax variation

- Use of questions/rhetorical questions

Analysis of each of these language and style features has been included in the chapter questions, however, the figurative language in particular deserves further examination. Gleeson’s use of metaphor and simile is original and highly effective, and provides a poetic cadence within the text. The teacher can provide students with the summary handout (PDF, 102KB) of some of the figurative language examples used in the text, in preparation for the activities below.

Exploring similes and metaphors

A simple game can be used to start off and get students thinking about language. This game is adapted from English teacher and blogger Robyn Neal. It involves the following steps.

- Students are each given three pieces of paper or sticky notes.

- They write down three nouns – one on each piece of paper.

- The nouns are then collected and drawn at random from a hat or box.

- The teacher will draw two nouns to start off with, for example ‘cat’ and ‘computer’. Students and teacher can then brainstorm all the things they have in common:

- both start with ‘c’

- both have a ‘t’ in them

- people purchase both

- both can die

- both can provide benefit to their owner

- both hate water

- both can be donated to charity

- The teacher then distributes one pair of nouns to each pair of students and they have the opportunity to create their own comparisons.

The outcomes of this activity are shared in a whole class discussion. The relevance of this activity is that those comparisons which show insight, humour, cringeworthiness, etc., are the most powerful. Similarly, authors and writers use language in inventive ways to avoid stereotypes and make us consider ideas in new ways.

Students can then complete a reflection on the activity using the provided exercise (PDF, 167KB).

(AC9E7LE03) (AC9E7LE04) (AC9E7LE07)

Synthesising task

Poetry about place

Your task

For this task you will produce a piece of poetry about a place that is significant to you:

- Part A is the poem itself.

- Part B is a statement of intention explaining how you developed your ideas and the specific language choices you used to present your poem.

Format

Your poem may be written in free verse or in stanzas, but should not use forms such as acrostic or limerick, etc.

Process

- Brainstorm all the places that are or have been of significance for you personally.

- Compose a list of adjectives that may be used to describe your place. Also consider your sensory experience of this place – what would one see, hear, smell and feel in this place?

- Start a draft of your poem, considering the application of some of the poetic techniques we have learnt about, such as adjectives and adverbs, metaphors and similes.

- Share your draft with a partner for 3-2-1 feedback (3 positives, 2 improvements, 1 interesting thing).

- Refine and develop your poem based on your partner’s feedback.

- Publish your final poem.

Requirements

- The minimum line length for your poem is 20 lines and the maximum is 30 lines

- The statement of intention should be approximately 150–200 words in length.

A handout of these task requirements is included here (PDF, 107KB).

Assessment

Attached is an assessment rubric matched to the Year 7 Achievement standards (PDF, 54KB).

Ways of reading the text

Mahtab’s Story is situated within a subgenre of journey and survival narratives specifically focused upon the experiences of refugee and asylum seeker child protagonists. The content presented connects with the contentious, divisive issues and political rhetoric concerning asylum seekers and refugees in Australia.

Cultural diversity

A postcolonial perspective examining the interactions between the story presented in the novel and the wider context of refugees and asylum seekers in contemporary Australian society is appropriate and relevant to the Australian Curriculum in studying this text. A postcolonial reading examines the interaction between cultural ‘others’ such as asylum seekers and refugees, and the dominant cultural paradigm. Literary analysis of postcolonial texts may centre on questions of colonial oppression, postcolonial identity, hybridity, cultural ‘othering’ and perceptions of the world. This terminology is rather sophisticated for a Year 7 audience, therefore the questions below address these issues in a more appropriate way:

- Which characters in Mahtab’s Story have power? Which don’t?

- How is Mahtab’s experience different and the same as your own? Is she like you or not?

- What concerns does Mahtab have about ‘fitting in’ in Australia? Does it seem like she will be able to keep the same identity living in Australia, or would it change? Should Mahtab keep some of her own identity or be expected to ‘fit in’?

- How are the asylum seekers in Mahtab’s Story treated? Is their treatment fair?

Refugee and asylum seeker quiz

This is intended as a frontloading activity to ascertain students’ existing beliefs and opinions relating to asylum seekers and refugees. The activity may be conducted with Caritas Australia’s PowerPoint quiz. Alternatively, the activity may be undertaken using an online tool such as Kahoot or Socrative. The benefit of using these online tools is that the responses may be displayed on a projector or screen, offering a ‘snapshot’ of opinions as live feedback. It is possible with both tools to make students’ names anonymous.

Virtual reality for exploring empathy

One of the performance tasks in this unit involves students producing a version of Mahtab’s Story using Digital Storytelling, by combining still images, narration, music and titles using a video editing app or software program.

An emergent area of digital storytelling involves the use of virtual reality (VR) technology in the hope of provoking an empathetic response in the user audience. The United Nations has been at the forefront of producing content with this intention. Partnering with filmmakers Gora Arora and Chris Milk, and the VR app developer Within, the UN has sponsored the production of the film Clouds Over Sidra, which provides insight into the experience of an eleven-year-old Syrian girl living in a refugee camp in Jordan.

Students may view the 360-degree video using a web browser on an iPad, desktop or laptop computer. When students have completed the experience, ask them to write a reflection in their learning journal, considering what was presented and how this has added to or changed their thinking about refugees and asylum seekers.

If technology is not available to support the experience described above, the use of a guest speaker or excursion opportunity would develop similar understandings.

(AC9E7LE01) (AC9E7LE04) (AC9E7LE05) (AC9E7LY04)

Q&A panel using the ‘Circle of Viewpoints’ thinking routine

If timing allows, this activity may be used to extend and challenge the thinking of more able groups of students. Modelled on the ABC television show Q&A, students examine the issue of asylum seekers and refugees from multiple perspectives. Students should view a segment of the show before this activity, to help them understand the type of discussion they are planning for. Students will be assigned roles as either host, panellists, or audience members. Using the Circle of Viewpoints thinking routine, students will write questions or provide responses, depending on their role. They should preface their questions or responses with the scripted element of the routine: ‘I am thinking about [issue] from the perspective of [their role]’. For example, students may be assigned in an audience role to think about whether children should be held in detention from the perspective of a medical doctor.

While the activity is being undertaken, the teacher could also ask students to ‘Live Tweet’ their responses to the discussion, either by writing down 140 character comments or contributing them to an online forum. It is at the teacher’s discretion whether this element is undertaken and if it would be appropriate with the group of students in an open or closed online forum – this will really need to be determined on the teacher’s assessment of the likelihood of the students participating respectfully in a ‘backchannel conversation.

To provide adequate background on the issue, some learning or research may need to be undertaken prior to this activity (see More Resources for useful websites). Students may also benefit from watching a clip from an episode of Q&A.

(AC9E7LA03) (AC9E7LE02) (AC9E7LY02)

Gender and (in)equality

There cannot be true peace and recovery in Afghanistan without a restoration of the rights of women.

– UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan

The novel encompasses many aspects of gender relations within Afghanistan under the Taliban, and the role of women in Muslim families. This context provides adequate focus for a feminist reading of the text.

Malala’s story

One way of engaging students in thinking about issues of equality is to make the context relevant to their experience. The story of Malala Yousafzai offers a way into this discussion. Malala’s story has become well known as that of a regular schoolgirl trying to access an education, only to be attacked and shot by the Taliban. Having survived this, she subsequently became a spokesperson for girls’ access to education, and in 2014 was the youngest ever recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. The film He Named Me Malala may be viewed as a supplement to this unit. A discussion guide to the film is also available.

Investigating statistics

Numeracy may be incorporated into this study through the investigation of statistics relating to the status of women in Afghanistan under the Taliban, and how this has changed over time. Students may research statistics and interpret these to produce an infographic poster summarising their findings. Some useful sites for accessing information include UN Women’s FAQs and the BBC’s statistics relating to women in Afghanistan. Some online tools for creating infographics include Venngage, Piktochart and Canva.

(AC9E7LE01) (AC9E7LY04) (AC9E7LY05)

Comparison with other texts

As noted already, a subgenre of literature presenting child protagonists as asylum seekers and refugees has emerged in recent years. There are many texts which follow similar concerns and themes to Mahtab’s Story, and these may be used as supplementary texts in this unit. Picture books, in particular, are useful supplementary resources.

Picture books

- Refugees* by David Miller

- Out by Angela May George

- The Little Refugee* by Anh and Suzanne Do, illus. Bruce Whatley

- The Arrival* by Shaun Tan

- Room on our Rock* by Kate and Jol Temple, illus. Terri Rose Baynton

- My Two Blankets* by Irena Kobald, illus. Freya Blackwood

* Reading Australia Title

Novels

- The Bone Sparrow by Zana Fraillon

- No Safe Place and the Parvana books by Deborah Ellis

- Boy Overboard and Girl Underground by Morris Gleitzman

- Songbird* by Ingrid Laguna

* Reading Australia Title

Non-fiction and multimodal texts

- The Happiest Refugee by Anh Do

- Titles in the Growing Up series published by Black Inc.

- Who Gets To Stay in Australia? (2019)

- Where Are You Really From? (2018–2020)

- Go Back to Where You Came From (2011–2018)

- You Can’t Ask That S2: Refugees (2016–2022)

Evaluation of the text

The text has a significant role to play in examining the human impact of refugee and asylum seeker issues, especially as children and young people are affected. The emerging genre in this area signifies a literary concern with presenting this point of view and mobilising political awareness of social justice issues. Through examining and reimagining the text, it is intended that students will possess a transfer of awareness and an understanding of the complexity of these issues.

Rich assessment task (receptive mode)

Digital storytelling

Your task

For this task you will produce with a partner, a digital story, providing a retelling of Mahtab’s Story:

- Part A is the digital story.

- Part B is a statement of intention authored by you and your partner, to describe and analyse the decisions made during the creation of the digital story, and their intended effect on the audience.

What is a digital story?

Digital stories combine the art of traditional story-telling with the use of new technologies, making stories more compelling, educational, engaging and creative. [They] combine the use of video, photos, art and audio such as music, narration and/or sound effects into a single presentation.

– Department of Education Victoria

What is a retelling/recount?

A literary recount retells events from an original text (e.g. novel, film), to entertain and inform others. Its features include: background information (time, character, place); description of the events in time order; and, it may end with a personal comment about the characters or events.

Format

There are many digital storytelling tools available and they will each create a product in a different format. You may wish to author an interactive picture storybook, a photo essay, a short film or a podcast; or another product altogether – the choice is yours! Some suggested tools are listed below:

Process

- When you have explored the tools available, decide on the format for your story.

- Decide which part of Mahtab’s Story your digital story recount will focus upon – will it retell the whole story, or just a selected part?

- Produce a storyboard to outline the product you hope to create, and show this to your teacher.

- Gather the resources required to compose your digital story (voice recordings, photographs, etc.).

- Compile and publish your digital story.

- Compose the statement of intention.

Requirements

- The completed digital story should represent 1–2 minutes of content, or the equivalent (depending on format).

- The statement of intention should be approximately 150–200 words in length.

A handout of these Digital Storytelling task requirements is included here (PDF, 114KB).

Assessment

Attached is an assessment rubric for this task (PDF, 54KB) matched to the Year 7 Achievement standards.

Synthesising ideas

In studying Mahtab’s Story, students should have learned about the issues of asylum seekers and refugees, developed an understanding of the text’s structure, themes and techniques, and engaged in creative responses to literature: in the poetry and digital storytelling tasks. This final synthesising task has students reflect on one of the key themes of the novel, in order to draw an empathetic response on the importance of family.

A concluding activity to the study of Mahtab’s Story could be the thinking routine I used to think, now I think, in which students compare the views that they had about asylum seekers and refugees, before, during and at the end of the unit.

As a way of brainstorming prior to undertaking the reflective essay task, students could be asked to create a family tree for their own family, and Mahtab’s family.

Rich assessment task (productive mode)

Family reflective writing

This task, along with a detailed guide as to how to go about writing a reflective essay are explained in full in the linked document (PDF, 233KB). Teachers should use their own discretion in determining whether having students write about family is appropriate within their own context. The essay prompt could be tweaked to refer more generally to ‘relationships’ or ‘hope’.

Your task

They talked less of him and more of their life before. They dredged up from their minds the memories of their home and their family, talking about Grandma, aunts and uncles and cousins until the pain of remembering became too great and they begged each other to stop. (p.50)

Family bonds play an important role in Mahtab’s Story and the hope of reuniting the family is what motivates Mahtab and her family to keep going.

Write a reflective essay in which you discuss the importance of family to you.

In your essay, you should link your ideas to those presented in the novel Mahtab’s Story, in relation to its protagonist Mahtab.

Assessment

Attached is an assessment rubric for this task matched to the Year 7 Achievement standards (PDF, 57KB).

(7 votes, average: 3.57 out of 5)

(7 votes, average: 3.57 out of 5)